- Be clear on your value proposition. Use data to understand who your students are and evaluate existing programs, policies, and services and redesign them based on the needs of your current and future student populations.

- Support experimentation and risk taking. Create an environment in which institutions and their leaders are encouraged to innovate and take risks and supported to do so.

- Be transparent and collaborative. Create opportunities for a shared discussion about the challenges and opportunities presented by student segment shifts and make the whole campus part of the solution.

We often think of today’s college students as if there is a single way to describe them.

We picture a “traditional” student (18-22 years old, attending full-time, financially dependent on parents, and living on campus) with the same goals, motivations, values, and lived experiences.

But a look at the data on who is attending our colleges and universities reveals there is no one single profile of individuals attending our institutions and a single description could not be further from the truth.

There are three meta trends in who today’s undergraduate students are that will significantly impact college enrollment patterns and future business models.

- The traditional undergraduate market is shrinking.

- The undergraduate student market is becoming more diverse.

- The undergraduate student market is becoming more segmented.

TREND 1

The ‘traditional’ undergraduate student market is shrinking.

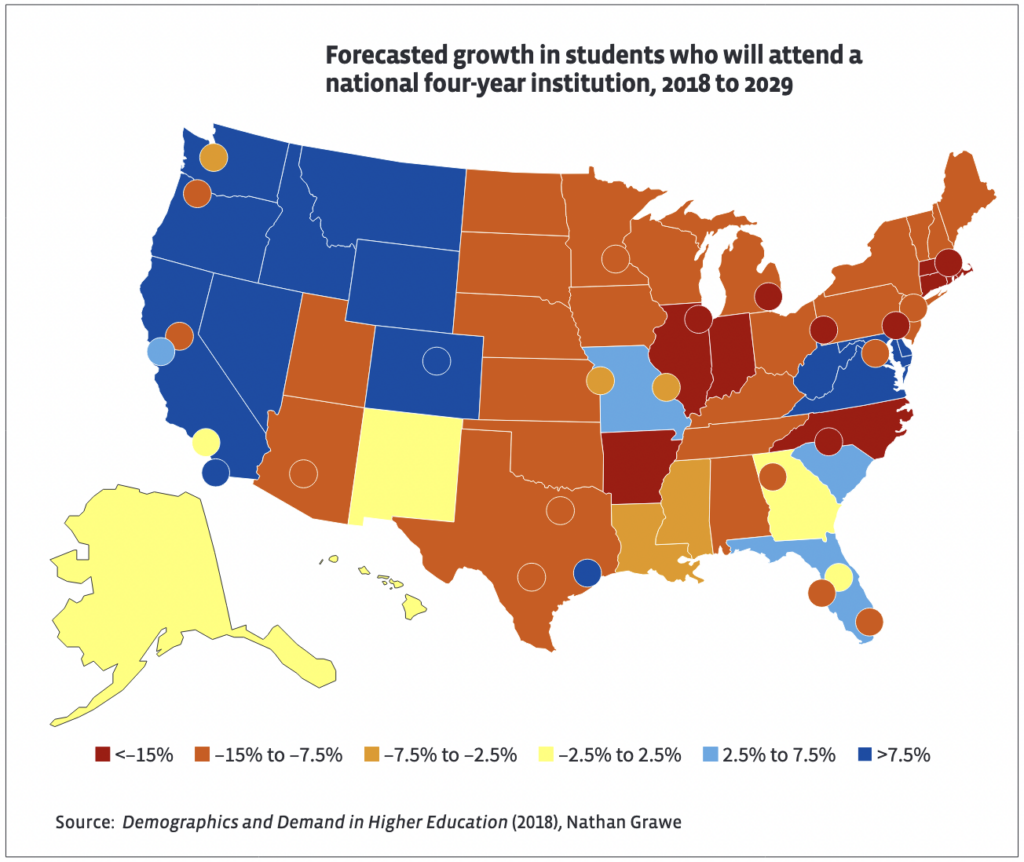

It is well-known that the number of students attending a college or university full time straight out of high school is getting smaller. The decline in births caused by the 2008 recession will be in full force across many areas of the country by 2025 and the declines in traditional student enrollment are expected to continue through the mid-2030s.

Nathan Grawe, an economist at Carleton College in Minnesota, explained how different types of institutions and parts of the country will experience the enrollment impact differently. The Northeast and Midwest regions of the country will see the most significant declines, while the Southeast and West will experience a smaller impact. The trend lines look the most challenging for regional public comprehensives and liberal arts colleges and community colleges, which will see declines of 5 to 15 percent across most areas of the country. Elite and national institutions, regardless of where they are located, are expected to see a smaller impact, and may even see enrollment growth, primarily because they have a larger applicant pool to draw from and can adjust their admission rates accordingly.

These trendlines are causing increasing levels of competition for fewer students. Institutions are making investments in programs, services, and marketing, and a change to admissions criteria and financial aid models in order to maintain current enrollments. Because of the decline in the overall number of traditional students, simply maintaining enrollments will be a less than zero sum game and will require significant new investments by most institutions to successfully compete.

TREND 2

The undergraduate student market is becoming more diverse.

Even as the number of traditional students declines, the demand for postsecondary education is growing in other segments, especially adult learners and students who are balancing education with other life demands.

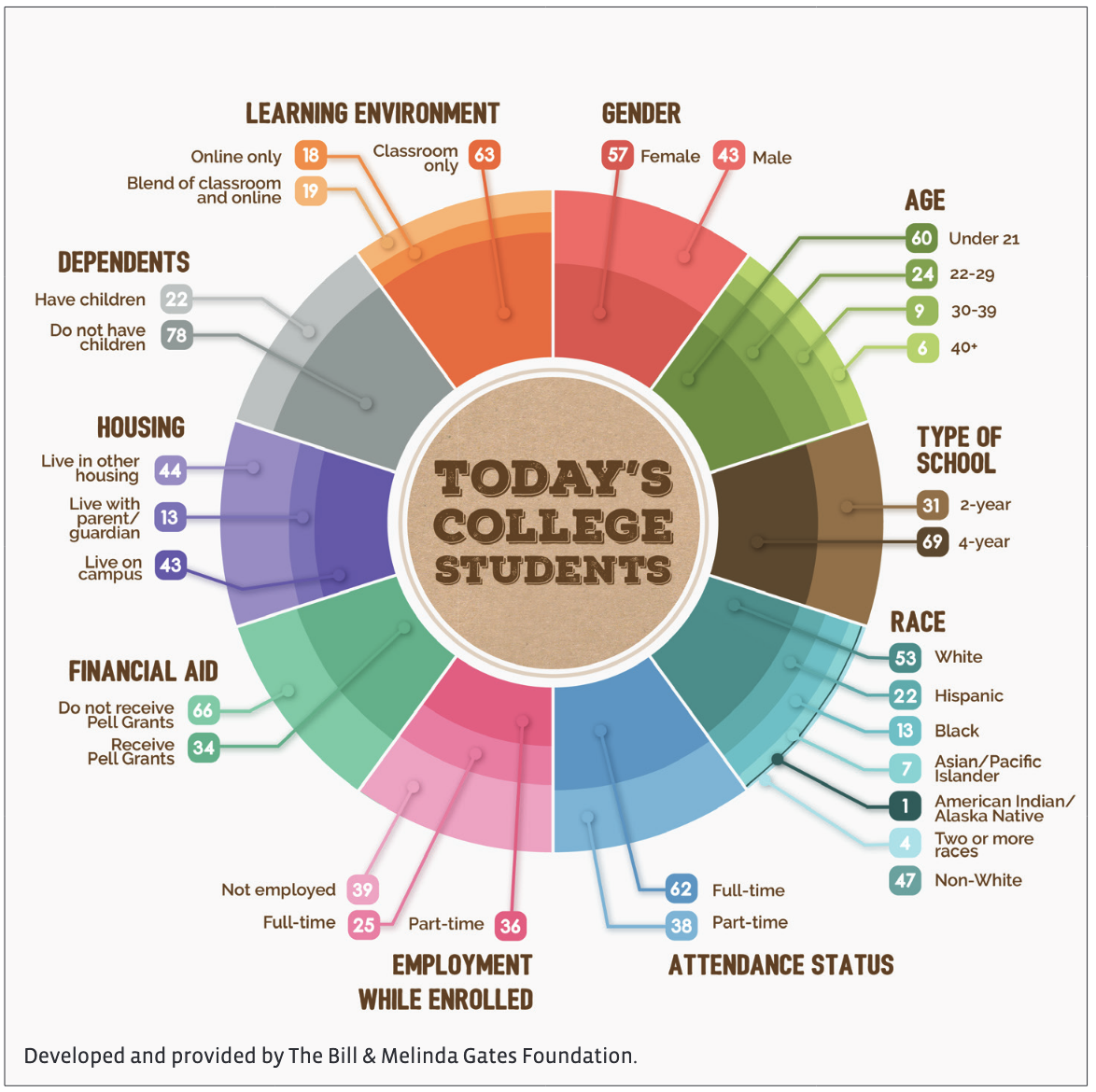

A recent graphic from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation captures this complexity. It breaks down America’s college students across an array of demographic and socioeconomic factors and provides a striking visual of how diverse our students really are. While these student populations create opportunities for enrollment growth, serving them will require the rethinking of many of the existing educational and support models, services, and policies. A few highlights:

- 40 percent of students are 22 or older. Many students do not attend college immediately after high school and instead return years later. These students, most of whom have work and family obligations, need flexible and affordable programs that offer credit for what they have already learned outside of the classroom.

- 61 percent of students work at least part time. Some students need to work to pay for their education; others are already in the workforce and are looking for a career change. Working students need flexibility so they can study at their own pace and on their own schedule.

- 22 percent of students have children. Raising children demands tremendous time and financial commitments—and so does attending college. To better balance the two, these students need flexible scheduling, financial support, and childcare options.

- 38 percent of students attend part time. Many of the demographic and socio-economic factors combine in a way that impacts some students’ ability to attend full time. Part-time students are less interested in on-campus amenities and are focused on cost, convenience, and accelerated programs that shorten time to degree.

TREND 3

The undergraduate student market is becoming more segmented.

Categorizing students into traditional and nontraditional categories provides some insights into their needs. But segmenting students according to demographic and socio-economic factors provides an incomplete picture of the goals, needs, and motivations of the students themselves.

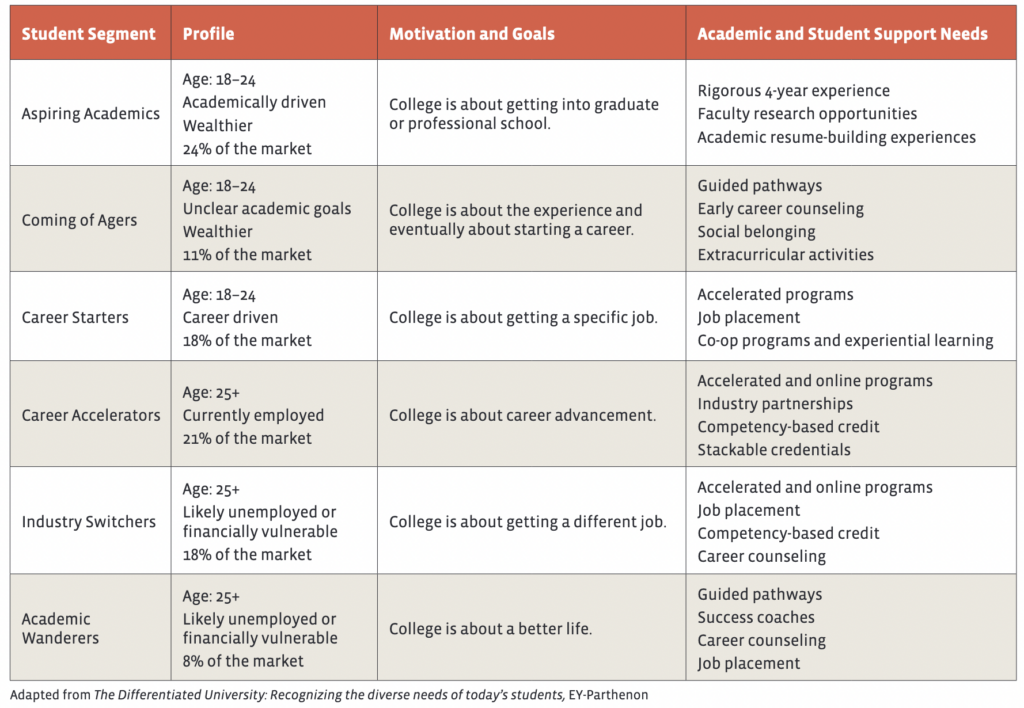

EY-Parthenon conducted a study of 3,200 students enrolled in college and found that when students are understood through the lens of their motivations and goals, they can be separated into six distinct market segments. Each has its own purpose for attending college, and each has academic and student support needs to help them achieve their goals. Three of the segments were within the traditional age profile but varied in their goals for college.

Aspiring Academics are the most academically prepared and driven. Their goal is to go to a graduate or professional school after completing their undergraduate degree. Institutions serving this population need to provide not only rigorous academics but also opportunities to build an academic resume, such as research with faculty.

Coming of Agers expect the full collegiate experience but do not arrive with a specific academic goal. They benefit from guided pathways, early career counseling, and co- and extracurricular activities that support belonging and career development.

Career Starters are extremely job-oriented and expect attending college to advance their specific career prospects. They are attracted by accelerated programs, job placement services, and co-op programs and internships that lead to their first job.

Like the Career Starter, the remaining segments are looking to college to improve employment prospects but are usually older than traditional students.

Career Accelerators are employed but aim to advance their career at their current company or within the same industry. They are primarily working adults with some prior college experience. They value things like accelerated and online programs, industry-based learning partnerships, competency-based credit, and stackable credentials.

Industry Switchers are going back to school to earn their bachelor’s degree to start a career in a completely different field. They are often in a precarious financial position or are unemployed. Like the Career Accelerator, they are looking for accelerated and online programs and stackable credentials but need career counseling and job placement services.

Finally, Academic Wanderers do not know exactly what they want from college but believe that obtaining a college credential will lead to a better life. They are more likely to be unemployed and have lower incomes and are the most at-risk of all student segments. They need more intensive supports, like success coaches and guided pathways, to help them identify a major track and stay on it.

Responding to changes in the student market

The decline in traditional enrollments has many institutions targeting nontraditional student segments for growth. But this is more easily said than done. Historically, higher education institutions have been designed to serve traditional students. Efforts to address the learning and support needs of students who do not meet that definition are often created as add-ons or are adaptations that keep that traditional student segment at the core.

The result has been institutions that are stretched beyond their capacity to effectively respond, as seen in gaps in persistence and completion rates for underrepresented and nontraditional student populations, and cost structures that are unsustainable.

A growing number of institutions are recognizing that to successfully respond to the changing needs of their students and do so in a financially sustainable way means clarifying their value proposition and redesigning historic approaches to programs, policies, pedagogies, and support services. They are using concepts of business model innovation and design thinking to guide their strategic transformation.

Business model innovation. A business model describes how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value. Business model innovation considers four elements of an organization’s function.

- Customers’ value proposition and how the organization will address the customers’ needs

- Value chain, which organizes processes, partners, and resources to deliver the value proposition

- Profit formula, which lays out how an organization will generate revenue

- Competitive strategy, which describes how an organization will compete with rivals and defend its position in the value network.

Design thinking. Design thinking is an iterative process in which organizations seek to understand current and future users, challenge assumptions of their existing products and services, and create innovative solutions that meet the unique needs of their target market and can be prototyped and tested.

At the core of these concepts is an effort to identify and understand specific student segments and to redesign programs and services in a way that is customized for that segment.

Rethinking business models and value propositions requires boards and leadership to ask a few probing questions about their students.

- What are their needs, motivations, and aspirations?

- What are their lived experiences and how does that impact their ability to successfully complete their education?

- How should the institution’s academic and business models and core operations be transformed with their target student segment in mind?

Instead of a one-size-fits-all set of programs and services, these approaches start with a research-based understanding of students and design programs and services to specifically fit their needs.

Here are some case studies of strategic transformation through design thinking and business model innovation

Northern Kentucky University’s Success by Design

When Ashish Vaidya became the president of Northern Kentucky University (NKU) in 2018, he entered an institution whose board was ready for strategic transformation.

“We had already started thinking about the demographics of the university from a DEI perspective and how we needed to reposition ourselves as a regional comprehensive university within a major metropolitan area,” says Andra Ward, the chair of the NKU Board of Regents. “We had started with a design thinking process as part of an Inclusive Excellence Symposium we organized and hosted a couple years prior.”

Before arriving at NKU, Vaidya had engaged in efforts to improve student success at multiple institutions but often encountered a standard response. “Every time I asked the question about why we weren’t retaining and graduating more students, I heard, ‘if only we had better prepared students’,” Vaidya says. “I heard every excuse in the book and yet we never looked inwards.”

At NKU, Vaidya encountered a board and institution ready for internal reflection and redesign. The board charged him to develop a plan to make NKU student-ready by questioning the historic practices and approaches that had been developed at an earlier time and for a different student population.

The NKU board asked Vaidya to create a plan in six months so the institution could begin the important work of becoming student-ready. “We told him that we don’t want this to take the next three years,” Ward says. “We understand and respect shared governance, but we want to accelerate the timing tremendously.”

Vaidya embraced the challenge and developed a process that was deeply participatory, engaging close to 600 stakeholders through interviews and focus groups, including faculty and staff, community leaders, and alumni.

The result was Success by Design, a strategic plan with a singular focus on student success. Success by Design’s framework consists of three pillars (access, completion, and career and community engagement), which guides how NKU delivers support, services, and programs to all learners—not just traditional students—by meeting the learners where they are in their educational journey.

As part of the implementation of Success by Design, NKU has created four major projects with the intent of redesigning the institution and its processes to better serve their students. One example is Tripwire Identification, which engages cross-divisional teams to identify and redesign internal processes such as admissions, financial aid, and accounts payable to make them seamless for students.

They also are leveraging the pillars of Success by Design to encourage broad campus participation and innovation across the institution. One signature effort is the Student Success Innovation Challenge. As part of the challenge, the leadership team solicits proposals and ideas from across campus to identify ways to redesign processes or improve student experiences.

“We thought we might get 5 or 10 proposals,” Vaidya says. “The fact that we got 133 blew us out of the water, but it also showed that there was just a lot of pent-up creativity that needed to be tapped.”

Ward and Vaidya admit that the focus on redesign doesn’t sound all that strategic but has been transformational for their university.

“Efforts like Tripwire or changes in policies and financial hold models— none of it sounds sexy but it makes a difference,” Vaidya says. “It helped solidify that becoming student-ready is not just a theme, it’s about looking at all of the things that get in the way of our students in navigating their journey.”

And it’s working. NKU reached its highest retention levels ever in Fall 2020. While they did see a COVID-related dip, they are projecting to see a bounce back to pre-COVID levels this fall. They also exceeded 8 out of the 11 performance funding metrics tracked by the Commonwealth of Kentucky.

“People are noticing, and it is a testament to all of the work our campus is doing and the support of our board,” Vaidya says.

The success of Success by Design has come from strong leadership and an engaged campus, but it is also a testament to an active and engaged board that saw the importance of becoming student-ready through strategic redesign.

“While in the search process and recruiting our next president, we were looking for someone who was bold, innovative, and transformative,” Ward says. “And that’s what Success by Design has been for us. It’s charting a new course for NKU, not in reaction but forward thinking about how this institution will look 25 or 50 years from now.”

Minnesota State System

Equity 2030 and Equity by Design

As the largest higher education system in the State of Minnesota and the fourth largest comprehensive system in the country, Minnesota State Colleges and Universities (or Minnesota State) has been feeling the impact of each of the three student meta trends across all of its 26 colleges and 7 universities.

As early as 2018, the board and system leadership began to recognize that historic models and approaches would be insufficient to address the changing needs of its diverse student populations that were enrolled at institutions in every corner of the state. Performance on important indicators highlighted the need for change.

The 2015 Minnesota Legislature enacted legislation setting a target that 70 percent of Minnesota adults age 25 to 44 will have attained a postsecondary certificate or degree by 2025. In 2015, only 57.5 percent of the population had a postsecondary credential, and the percentages for people of color were 10 to 20 percentage points lower depending on racial or ethnic group. As the higher education system serving the greatest number of students of color and nontraditional students in the state, Minnesota State felt an acute responsibility for improving the educational opportunities and outcomes for all student populations.

“Trends were converging that pointed to the need to rethink how we are designing and delivering our programs and services that better reflected the diversity of our students,” says Devinder Malhotra, the chancellor of the Minnesota State system. “Our enrollments were declining while workforce demands for individuals with postsecondary credentials were increasing. We needed to understand how to improve access and completion rates of diverse communities [that] historically have had low participation and completion rates.”

Their challenge was that most of the processes and systems within Minnesota State had been designed to serve a very different population of students. It became apparent that Minnesota State must adapt and change its systems and cultures to meet the needs of today’s students rather than expect today’s students to learn or adapt to the systems and culture of yesterday’s higher education.

“Our institutions have always been focused on this work, but the equity gaps persisted,” Malhotra says. “Existing policies, practices, approaches, and organizational structures all supported the status quo. We needed to be more deliberate in dismantling existing structures so new innovations can emerge and be scaled up.”

In June 2019, the Minnesota State Board of Trustees set an ambitious goal that by 2030, Minnesota State will eliminate educational equity gaps at every Minnesota State college and university. To achieve this goal, the system launched Equity 2030, a comprehensive redesign framework targeted at intentional systems and culture change fueled by innovation at the system and institutional level.

Equity 2030 emerged out of a year-long, board-led exploration to reimagine the future of higher education and improve Minnesota State’s ability to respond to the demographic, technological, and economic forces impacting the system through strategic innovation.

“As a board, we spent a year studying the national trends and approaches to change and innovation in higher education,” says Jay Cowles, the chair of the Minnesota State Board of Trustees. “It was a collaborative and transparent process to understand our challenges, and out of that study emerged Equity 2030.”

Minnesota State sees Equity 2030 as its moonshot goal.

“Equity 2030 is our NorthStar and our organizing principle. It impacts our work in all of our adaptive challenges whether they relate to student success, workforce development, increasing the relevance of our academic programming or revenue enhancement. It is the anchor for the redesign of the operational structures, policies, procedures, and practices to create an inclusive, safe, and supportive ethos for ALL students,” Malhotra said.

Minnesota State has created multi-institutional and collaborative structures, such as centers of excellence and communities of practice, to develop innovations and scale them across the system. They have also leveraged formal design thinking approaches, including Equity by Design, which is a formal design framework that applies an equity lens to teaching and learning, and an Equity Scorecard to monitor progress on closing the equity gap across race and ethnicity, economic and family income, and first-generation status.

Minnesota State sees grassroots innovation as key to successfully achieving the goals of Equity 2030. This includes intentionally prioritizing capacity-building to make change across all levels of Minnesota State and empowering individuals regardless of title or responsibility to examine, explore, and experiment with evidence-based innovation to close attainment gaps.

“Equity 2030 has allowed us to shift the conversation,” Cowles said. “Systems are often viewed as top-down, but the power lies in the horizontal. Systems provide a tremendous opportunity to experiment.”

Enacting change of the magnitude envisioned by Equity 2030 is challenging, and the leadership from the board and the partnership between the board chair and Minnesota State system leadership are vital to successful implementation.

“In times of change, close communication and coordination between the chancellor and chair is critical,” Cowles says. “The board must work very hard to make the pressures facing the system visible—the tough questions we are facing and the issues we are grappling with. We must make sure that our agendas and processes are creating as much trust as possible, including with the broader public.”

In the end, Malhotra believes the system’s commitment to equity strengthens the value proposition of public higher education and creates a compelling argument for ongoing investment.

“Equity 2030 is a moral imperative,” Malhotra says. “It is also the path to economic prosperity for not only our students, but also for the state of Minnesota.”

University of Redlands – Business Model Innovation

Like many private liberal arts colleges in the U.S., the University of Redlands has been grappling with issues related to declining enrollments driven by demographic changes and increasing competition.

When Krista Newkirk became the institution’s 12th president, she encountered an institution with established traditions, a committed faculty and staff, and a board ready to partner with her to develop a strategic agenda that would address these challenges and guide the institution into the future.

“One of the things that really drew me to Redlands is that it has always been forward thinking,” Newkirk said. “From its very conception, it really strove to be a liberal arts institution layered with a professional focus.”

But as the external environment, demographics, and the needs of students were changing, it was putting pressure on the University of Redlands to once again be forward thinking.

As Newkirk began to explore how to move forward, it became clear that in order to position the institution for long-term financial sustainability, the University of Redlands needed to fundamentally rethink its business model in a way that allowed the institution to maintain its core mission and traditions while addressing the needs of tomorrow’s students and employers.

“The business model no longer works,” said Jamison (Jim) Ashby, the chair of the board of trustees. “We have the financial stresses of having a high fixed cost. The market is shifting. We needed to make a strong pivot in order to better serve our students in the future.”

Their “strong pivot” was to forgo the traditional approach to strategic planning that focused on incremental adjustments, and leaders instead launched a process to reinvent the University of Redlands business model and clarify its value proposition for a new generation of students.

“With the financial pressures facing our students, having a clear value proposition is more important than ever,” says Newkirk. “A university education is a big investment. And it is key for us to show our students and their parents that it is the right investment.”

Guided by David Rowe, AGB senior consultant and practice leader for private higher education and foundations, the University of Redlands board, leadership and campus community engaged in a 9-month process of combining the historic strengths of the university with market research on current students and regional employers to a strategy agenda that drove business model innovation.

A key component of their emerging strategy agenda is a recognition that the University of Redlands serves multiple student segments at its main campus in Redlands, California, and its second campus in Marin, California. Each of the student segments requires different educational programs, delivery models, and support services. So as part of its refined value proposition, it will be developing customized approaches depending on student markets served through destination and distributed digital offerings. They also are developing a design lab to support and guide faculty and staff as they innovate to better serve each student segment and their unique programmatic, pedagogical, and support needs.

“I think we all collectively understood that the institution has been student-focused but that the students have changed,” Newkirk says. “COVID has really driven some of that change, so it was a good time for us to come back and make sure that what we think the students need is actually what they need and meet them where they are.”

As the university moves toward refinement of its business model innovation agenda, engagement with all campus stakeholders continues to be key.

“Every great challenge is met by people who together identify, recognize, and acknowledge a challenge and then unify around a cause,” Ashby says. “This has been an opportunity to get all of our stakeholders to the table, to agree on the problems and the challenges, and to come up with a solution that will allow this university, with its 114-year heritage, to meet the moment once again. To do what we have always done but do it in different ways and serve different constituencies than we did 20 years ago.”

Also critical is the strong partnership between President Newkirk and Chair Ashby and a relationship that is built on trust and a shared set of priorities for the university.

“As a confidant and partner with the president, my role is to be a sounding board.” Ashby says. “I provide her a safe place to share concerns and ideate around strategic issues.”

And increasingly addressing those strategic issues and tackling some of the most entrenched areas of the traditional higher education business model will require innovation, experimentation, and a willingness to try things with no guarantee that they will be successful.

“Jim makes a point that if you’re not failing, you’re probably not striving far enough,” Newkirk says. “The grace to try things is a real gift. It allows you to move forward in ways that are often stymied in higher education.”

Lisa Foss, PhD, is an AGB senior consultant in the areas of strategic planning and transformation, academic and business model innovation, academic program portfolio management, and brand-strategy integration. She also serves as the ambassador to AGB’s Council for Student Success.