- Misalignments in stakeholder understandings of the purpose of college, the kind of experience students should have, and what students should gain is common across all types of colleges and constituencies

- Messaging to students typically focuses on campus amenities rather than academics

- Trustees and leaders need to engage in conversations about the purpose of higher education and the mission of the institution

- Students should be onboarded to the primary mission from day one

Suppose you were commissioned to visit a company or an institution. As an investigator—perhaps a visitor from abroad or from McKinsey—you might ask the various persons you encountered why they were there, what they were doing, what they hoped to achieve, and how they knew whether they had achieved success. You would also survey the daily activities and take notes on what you saw, heard, and overheard. Suppose you found little coherence—the organization seemed all over the map—you might even wonder whether it deserved to exist at all. Even if you encountered strands of consensus about goals, you would be disappointed in the absence of evidence that goals had indeed been achieved.

We have recently completed a study and published a book about the American college scene. While there are some areas of consensus, and scattered outcomes to cheer, the overall situation is disheartening. But it does not have to be this way. In what follows, we outline what we did, what we found, the problems we encountered, and how we think that they can be fixed—to the advantage of the participants, and the broader society.

Going Wider and Deeper: The Real World of College

Over a decade ago, as long-time researchers in education, we became concerned about the sense of direction, of purpose, of young people, especially those in college. Few seemed to have reflected seriously on what they were doing, why they were there, and what they hoped to achieve from higher education. While there is hardly a dearth of books about college, most works are based on slender data (for example, about one school or type of school, and on multiple choice or short-answer surveys). We sought to go wider and deeper.

Accordingly, we undertook what may well be an unprecedented study of American colleges—featuring in-depth conversations with major stakeholders across diverse colleges and universities. In all, we conducted interviews with more than 2,000 individuals from 8 different constituencies—500 incoming students, 500 graduating students, several hundred faculty and administrators, as well as hundreds of parents, young alums, and job recruiters—and importantly, nearly 100 trustees.

We sought to understand the “alignments” and “misalignments” between and across the constituencies—to investigate if stakeholders agree about the purpose of college, the kind of experience students should have, and what they should thereby gain. And when struck by misalignments, we pondered how best to align them.

In semistructured interviews we asked all participants more than 40 different questions, both straightforward questions (for example, What are your goals for the college experience? What is the biggest problem on your campus? What courses are “time well spent” and “wastes of time?”) and open-ended questions (for example, If you were the “czar” with absolute authority at your college, what three changes would you make to the academic program? What book would you give to a graduating student? If you were given a free week on campus, how would you spend your time?). Of course, we edited questions to be appropriate to the identity of the person (first-year student, trustee, dean) to whom we were speaking.

We listened to what people said, but equally—and importantly—to what they did not say. Indeed, sometimes the absence of discussion is just as important as what individuals actually do mention. For example, surprisingly, we rarely heard students discuss topics of finance, social media, ethics, or free speech (what we now refer to as “cancel culture”). We also noted when individuals came up short. With respect to the “czar” question, most participants did not have any innovative ideas for changing the curriculum (even when awarded absolute authority). Importantly, because every institution that we studied called itself a liberal arts school(1), we were interested in how participants would discuss the concept during our interviews. Few participants spoke about it unprompted. The lack of mention, in and of itself, is notable. To delve further, at the end of the interview, we explicitly asked “What does the term “liberal arts” mean to you?” a less confrontational way to probe their understanding. Except for faculty and administrators (60 percent of whom offered a reasonable definition), no other constituency could offer a reasonable parsing. The lack of clarity about this “term of art” is telling.

After a decade of research and analysis, we presented our findings and recommendations in The Real World of College: What Higher Education Is and What It Can Be (MIT Press 2022) along with many articles and blogs.

Major Findings:

Alignment and Misalignment

Across ten campuses—public and private, large and small, highly selective and not selective, commuter and residential—we were struck by the alignments and misalignments across constituencies.

In our study, we found one major misalignment. On one side, one finds most constituencies, the group of students, parents, and alums. On the other, one finds the faculty and administrators—who are principally responsible for structuring and carrying out the college experience. As one concrete example, students and their parents are in more agreement with one another about the scope and purposes of higher education than they are with the individuals whom they see regularly on campus and who presumably have primary responsibility for their well-being and growth.

Turning to constituencies of particular interest to readers of this publication, trustees and job recruiters are in more agreement with one another than they are with faculty and administrators. Moreover, students and trustees are in more agreement than they are with faculty and administrators.

This significant misalignment is one of the major headlines of our study. In fact, faculty and administrators seem to be “on their own island”—apparently unaware, or unconcerned with, what the other stakeholders believe is most important to bring about in college. And vice versa.

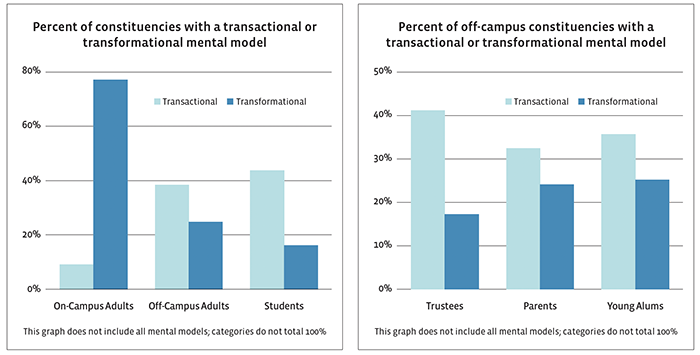

Our research found that students across every campus express a “transactional” mental model for the college experience—they see college primarily as a means of developing their profiles and resumés—to get high grades, build networks, gain leadership positions—all in the hope that these “badges,” will lead to employment (hopefully, a lucrative job), or possibly admission to graduate school. Fewer students approach college as an “exploratory” experience— to marinate in new ideas, activities, and people. Even fewer students are “transformational” about their college experience— viewing college as a special time when they can reflect, reconsider, and possibly alter their ways of thinking, beliefs, and values.

In dramatic contrast to other constituencies, more than three quarters of faculty and administrators across every campus express a “transformational” model for the student college experience(2). Clearly the aspirations of the faculty and administrators deviate a great deal from those of students, as well as the bulk of off-campus constituencies.

Some might predict that faculty and administrators at the less selective schools or nonresidential schools might prioritize helping students “get through” the experience—not the case! In fact, in comparing faculty and administrators across schools, one of the highest percentages of “transformational” faculty and administrators is at one of the least selective schools in our study. Faculty members at this school explain that they aim for their students to “see the world in new informed ways,” and to “see themselves as important players in this world…”

Equally revealing, one of the lowest percentages of “transformational” faculty and administrators is found at one of the most selective schools in our study(3). We wondered whether the messages that seem to permeate the institution are so strong that the faculty and administrators have also begun to embrace these views. At this school, faculty testify that, to foster bonds with students, they focus on how a course of study might help students find gainful employment after graduation. One faculty member explains:

I think that one of the reasons that students come is to be prepared for a job market. And one of my goals for them is to prepare them for a breadth of opportunities in a job market…. But in doing that, to also expose them to…the subject areas that I teach…so that they have the information that they need to have in order to really decide for themselves what they really wanna [sic] do. Because that’s primarily the process that they’re going through here.

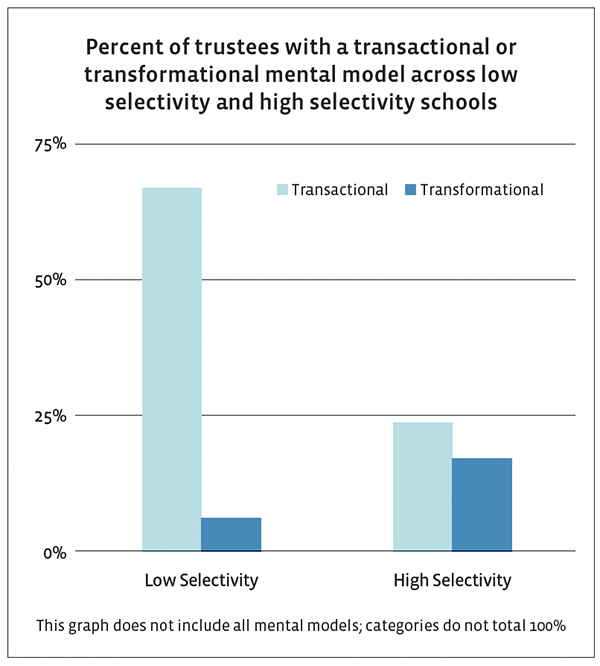

Unlike faculty and administrators, significantly more of the “off-campus” constituencies in our study (parents, young alums, job recruiters, and trustees), embrace a transactional view. In fact, as compared to other off-campus constituencies, more trustees express a transactional mental model, and fewer trustees express a transformational model for the college experience.

One trustee speaks to this misalignment (without prompting) in giving advice to a hypothetical first year student:

I get booed off the stage by professors when I say this, don’t take [courses with] professors [who] are known to fail students. Just don’t do it. I don’t care who it is. I don’t care if it’s, you know, [the] former President of the United States or [a] member of Congress teaching a course. If that academic has a reputation of messing up GPAs…you need to know that…carefully research the professors and make sure…that you’re taking the right professors…[who] are going to enhance you and enhance your GPA.

Another trustee highlights how his views about outcomes of higher education differ from those of faculty:

It’s interesting how…college professors, a lot of folks on the academic side, feel that…you know even if a student comes in and only stays a semester and doesn’t get their degree, they’re a lot better off than if they hadn’t come at all because, you know they took a philosophy course—they may learn something that will better them in life, whether they get a degree or not…But, I think at the end of the day, and again maybe because I’m doing a business perspective…but to me, it’s not just getting a degree. It’s that they’re prepared to enter the workforce.

Yet another trustee sums it up: “My ambition for the university, is to do whatever’s necessary to try and afford our students the best possible opportunity, to be gainfully employed and an opportunity that provides them with a career path, when they graduate… it seems like you know, the world has evolved to a point where you need to have certain skill sets to be successful in a post-college experience.”

Importantly, we also find differences across schools. More trustees at the high selectivity schools express a “transformational” mental model, as compared to trustees at the low selectivity schools; and fewer trustees at the high selectivity schools express a “transactional” mental model, as compared to trustees at the low selectivity schools(4). Also notable: Recall that more faculty and administrators at one of the least selective schools in our sample express a transformational mental model than faculty and administrators at other schools, yet more trustees at this same school express a transactional mental model

than trustees at other schools! In our view, no doubt our hypothetical visitor would be struck by such a massive misalignment.

While students’ focus on jobs and salaries may well reflect parental concerns, one should ponder the messages trustees convey to the institution and its stakeholders. Indeed, two of the most frequent words among all trustees are “money” and “business.” These words did not appear frequently, if at all, from any other constituency. We note, of course, that many trustees are parents—and so they are wearing dual hats. Still, in our study they were speaking to university-based researchers and would presumably have had little motivation to minimize transformational aspirations.

What Do We Make of These Findings?

Our hypothetical visitor cannot fail to be struck by a lack of explanation—on the part of most constituencies—of why one might go to a nonvocational college rather than simply spending four years on job training.

While the bulk of faculty and administrators express academic goals for students, students and their parents focus on “academic success,” getting good grades and high GPAs—which will eventually garland a resumé. As we put it, students, parents, and trustees are focused on earning rather than learning. Whether visitor or researcher, one begins to wonder: If most people believe that preparation (for the first job) is the primary purpose of college, why do institutions spend precious resources on all those faculty from a wide disciplinary spectrum? Why do institutions feature libraries, museums, and research facilities?

Putting this another way: If colleges claim to be vocational—for those schools specifically focused on training students to become a veterinarian, journalist, pharmacist, or commissioned soldier—that is their mission and they should deliver on that promise. But if an institution of higher learning claims to be focused on the liberal arts and sciences, to provide a broad education, to help students become “well-rounded,” it needs to make good on that promise or at least be explicit about what a school can and can’t deliver. Indeed, that is presumably what our hypothetical visitor from McKinsey would say!

The Reason: Mission Sprawl

In the course of our study, rarely—if ever—did we hear the word “mission.” In fact, from text analysis, we know that when it is spoken, it is often used as a part of the word “admission.”

On the one hand, this is surprising. But, when we examine the mission statements of the ten schools participating in our study, we begin to understand why few participants utter the word “mission” or even discuss it in concept.

At each school, we see lofty ideals that higher education can bring about—promises of “leadership,” “citizenship,” and “professional preparation.” The word cloud illustration shown on page 17 reveals visually the overall importance of key words used in the mission statements at each of our ten schools.

But a single institution can’t possibly deliver on all promises for all people. Perhaps a whole sector can, but not a single institution. Indeed, and tellingly—the development of the mind (or an equivalent aspiration)—does not stand out.

We call this “mission sprawl.” Put bluntly, this dispersion explains how students and parents can well miss an important—if not the most important</em —rationale for a higher education that is not avowedly vocational.

We identify three primary reasons for this current state of affairs.

1. Messages to students—from all constituencies and from early ages.

Mission sprawl is a collective problem—due to many causes. Every individual and constituency should reflect on the messages that are given to students—both implicit and explicit—as early as middle and certainly high school.

A surprising and disturbing observation: Having taken tours and attended information sessions across campuses, we were struck by the “transactional” messages given by nearly every institution. We heard a lot more about clubs and dining options—on and off campus—sometimes about internships or travel abroad—but little about academic majors, ethics, research centers, or laboratories.

2. A society that is increasingly ambivalent about college.

Our study appears at a time when the value of higher education has been broadly questioned. Indeed, in a 2018 Gallup poll, fewer than half (48 percent) of U.S. adults reported a sense of trust in higher education—a steep decline since 2015 in which this percentage was at 57 percent(5).

We note that this critique is not consciously focused on universities—whose scholars explore new areas of research—for example, in health or in technology, or who train professionals. Rather, the criticism alights on four-year nonvocational schools; these are condemned for their cost and for the belief (well-founded or not)

that they foster critiques of contemporary society.

Accordingly, it is understandable—but in our view shortsighted—that individuals, such as students and parents who are the “customers,” wonder about “value” and seek convincing evidence about the most readily available data for “return on investment.”

3. A laser-like focus on “the bottom line.”

To please “customers,” leaders feel beholden to students and parents to meet their stated needs. As a result, “the bottom line” has become focused on filling seats, the retention of students, rankings, and fundraising. “Admissions” is now referred to as “enrollment management;” departments compete for students to major in their disciplines, and trustees are selected in part because of their capacity to give or raise money.

Most of the trustees with whom we spoke emphasize the importance of “marketability” of the institution by a focus on maintaining or improving the reputation of the school, to stay ahead of other colleges.

One trustee describes these priorities:

…Before I’m done, I’d like to get the yield above 50 percent, and I’d like to get the acceptance rate in single digits. Not that I can control that, but I think it’s indicative of the fact that the school’s more attractive. So the student body is reasonably good. I think the athletic program is pretty good, and we actually—we’re in pretty good shape there compared to a lot of other football factories and basketball factories.

Another trustee suggests that the goal of college is to make students “marketable”:

I also feel very strongly, and I know this is a point of contention in some circles, that there should also be very strong… internship opportunities and that the college also should be playing a strong role in making these students marketable. And that would either be marketable in order to pursue a PhD and knowing what that would entail, or being marketable to pursue employment in the workforce, and that involves knowing in advance the value of references and a strong resumé.

This transactional approach to college is notable. Many educational leaders outside the United States admire and try to emulate our well-known four-year colleges (from Amherst to Yale), with their launching of several hundred liberal arts and sciences institutions (some are branch campuses of American institutions). We

wonder whether these emulators may be more cognizant of the value of nonvocational education, while some of our leaders have “lost the faith” or at least are reluctant to voice it.

Our Principal Recommendation: Identify and Articulate a Central Mission for Nonvocational Higher Education

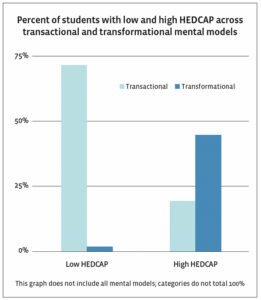

Colleges that describe themselves as offering a broad, general, liberal arts education—rather than an explicitly vocational one—should practice what their description promises: a once in a lifetime opportunity to help students think better, deeper, and more analytically, and to express themselves cogently. We call this Higher Education Capital (HEDCAP, for short)—an ability to attend, analyze, reflect, connect, and communicate on issues of importance. We believe that this should be everyone’s “bottom line.”

Using rigorous measures to assess HEDCAP for each individual (including “blind scoring” in which every individual is de-identified), we find the average HEDCAP in our schools is greater for graduating students than for incoming students. That’s good news! But HEDCAP does not increase by the same rate. Students at some schools show more HEDCAP “growth” than students at other schools, and notably at one of our schools, HEDCAP does not increase at all. Instructive and sobering: there is virtually no difference in HEDCAP when we compare the graduating students to the young alums; you are not likely to increase your HEDCAP once you graduate—and it may even diminish.

Importantly, our data show that student mental models for the college experience predict HEDCAP “growth.” Students who express a transactional mental model for the college experience are more likely to have “low” HEDCAP. In contrast, students who express a “transformational” mental model are more likely to have “high” HEDCAP. Simply put, mental models matter.

Perhaps surprisingly, the job recruiters agree. Recruiters and employers express a desire for workers who have high HEDCAP—as noted, the abilities to attend, analyze, reflect, synthesize, and communicate. Several employers stressed that they can teach job-specific skills in weeks.

As an example, a job recruiter in a start-up business explains that students can be trained to do any particular job, but he values that college teaches students “how to think”:

…When you go to a four-year school, especially, it’s not a vocational school, they don’t teach you how to write emails to customers. They’re teaching you how to think. They’re teaching you how to find information…I think employers need to understand that searching for the ‘right’ candidate or for the ‘right’ employee for six months, or a year or two years makes no sense, when there’s somebody who’s highly qualified and available today who might just need a month of training.

Reflecting these sentiments, a job recruiter in retail states, “a formal college education no matter what you’re studying, in most classes you’re forced to think…it’s a skill that you just have to use over and over and over again to get better…college is very important for developing independent thought.”

Our overall bottom line: Starting in the boardroom, trustees and leaders need to engage in conversations about the purpose of higher education and the mission of the institution. The goal should be “mission possible”—alignment among groups about the primary focus on learning and intellectual development—which should be conveyed to all interested students and families directly from a first interaction with the school (some call this Day “0”).

Then, from the first day on campus and continuing over the course of college, students need to be onboarded to this primary mission. If there is a second mission (for example, religious, military, civics, great books, or job preparation, etc.), this needs to be carefully intertwined throughout the college experience—both in the academic program and cocurricular and extracurricular activities offered on and off campus.

To be sure, it is not our job to tell educational institutions what their missions should be. As noted, more than one mission is possible. But if the mission of the school is simply to improve the chances of employability—fine—but then the school needs to explain how it differs from Goldman Sachs University, Disney College, or Google U. Our proverbial consultant should look for not just the statement per se, but rather how it is embodied in daily work and daily life—in the minds and sinews of the inhabitants.

Stepping back, we can say with confidence that few, if any, faculty and administrators at liberal arts institutions would want the primary mission to be preparation for the world of work. Yet, most other constituencies lean in that direction. The challenge for the sector: Should faculty change, should other constituencies change, or should they search for a reasonable middle ground?

A Message to Trustees

We realize our findings and takeaways may not be agreeable to some of you, though the findings should be taken at face value. That’s fine—we stand ready to discuss, debate, and learn! Perhaps, indeed, there is a way to square the circle—to combine a desire to explore and to be transformed, along with demonstrated preparation for the world of work and not simply the first job, which may well disappear within a few years.

Final thought: As trustees of higher education, you have an indispensable role for the institution and for a sector that is vital for the society, and will be even more vital, as the global hegemony of the United States fades away. Furthermore, you have a responsibility to the students of your institution—to help create a desire and capacity to be lifelong learners and productive citizens who can address and help solve “real world” problems.

We call for:

- Institutions that clarify their central mission—how places of higher learning differ from other sectors (including financial and business institutions);

- Students and parents who understand the mission and how it relates to their own aspirations;

- Faculty, administrators, and trustees who embrace it; and

- Young alums who can readily draw on it.

In the best of worlds: College should constitute a long-term investment for the individual, but equally for the broader society.

Wendy Fischman is a project director at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and lead author of Making Good: How Young People Cope with Dilemmas at Work.

Howard Gardner, PhD, is the John H. and Elizabeth A. Hobbs Research Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education and the author of A Synthesizing Mind: A Memoir from the Creator of Multiple Intelligences Theory (MIT Press) and many other books.

The authors wish to thank Richard Chait, PhD, professor emeritus at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Endnotes

1. We included a range of schools in our study, from small liberal arts colleges to large state universities. At every institution, we interviewed individuals associated with the liberal arts and science program. As a comparison school, we also included an undergraduate engineering school.

2. On average, faculty have slightly higher expressions of transformational mental models than administrators (75% as compared to 72%).

3. The average percentage of transformational faculty and administrators across all schools is 78%. The percentage at each school ranged from 66% to 89%. At this school, 66% of faculty and administrators are “transformational.”

4. For further detail on the mental models of trustees and other off-campus constituencies across all categories of selectivity, please refer to The Real World of College, pages 157–164.

5. https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/242441/confidence-higher-educationdown-2015.aspx