- Examine how philanthropy at your institution contributes to the public good

- Ask leadership to be clear on priorities and seek ways to craft a joint vision with a donor

- Connect current research on philanthropy to your fundraising strategies

- Understand that foundations have boards, missions, and strategic priorities of their own. Approach those whose understanding of the public good resonates with your own.

Every era has its reigning narrative about the purpose of higher education. Our current, pressing noble purpose, one that reflects the aspirations of many colleges and universities, is to bring people in from the margins of society. You may be skeptical that higher education, among all the other actors in society, is uniquely positioned to do this. But this is increasingly the expectation—one that much of philanthropy is supporting.

We have developed this inclusive ethos at a time when higher education has become one of our polarized nation’s most prominent cleavages—between those who have a bachelor’s degree and those who do not.[1] It is not surprising that philanthropic attention is turning toward making college more accessible to more people, and to supporting their success. Expanding access means embracing students who enter higher education with fewer resources and prior advantages.

Furthermore, in our turbulent times much of philanthropy has become impatient. It seeks transformational innovation and change because it considers the crises we face to be too deep, too existential, and too immediate to be satisfied by simply sustaining the ways in which we are accustomed to doing the work of higher education. The ways we instruct, the curricula we offer, the way we connect to employers and communities, and even the kinds of institutions we design to provide and validate education are all eagerly being opened to reconsideration by this transformational approach.

But before you circle the wagons and respond with the success of American higher education as a world leader, consider the possibility that significant change is called for and that philanthropy can be a useful tool in both assessing the need for transformative change and designing its implementation. Philanthropy has played a formative role in higher education in the past and it may yet do so again.

Philanthropy and higher education both intend to serve the public good. What trends are shaping philanthropy’s role in higher education, the unique role foundations play, and the kinds of resources that are available to higher education leaders as they engage their moral imagination to advance the public good?

These reflections are based on my experience in a workshop hosted by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy in December 2022 that convened education leaders, scholars, and funders to discuss how the connections between philanthropy and higher education could better serve the public good. This is my personal interpretation and does not represent the views of the workshop or of its participants.

Considering the Public Good

Presidential valedictories celebrate how much money they have raised. It is a mark of performance and achievement. But what is behind the celebration of dollar amounts? What is their impact? How are they contributing to the public good? At some level, more money is better than less, but some dollars can be deployed with greater impact than others. In a context of unequally distributed philanthropic dollars, there is a growing chorus of informed critics claiming that donations are not going to the right places, to the most important purposes, or through the right kinds of decision-making processes.[2]

They lead us to ask the purpose of philanthropy and what options there are to better align it with public needs in higher education.

Philanthropy is clearly an important source of revenue, but it is different from tuition and government support in that it is given without an expectation of material return to the donor. The expectation is instead that the benefit will accrue to the public in general. This is why governments offer deductions and credits for philanthropic gifts to nonprofit organizations. Integral to their mission is serving the public good. So, is your college or university indeed advancing the public good with the philanthropic funds it is soliciting and receiving?

For those of us who work for or steward these institutions, we have commitments that make an answer in the affirmative seem obvious. Why else would we be here? But the question bears asking if we are to be faithful stewards of the public trust.

We seek to preserve what we value about our colleges and universities, often seeing philanthropy as a means to that end. Perhaps that is why we laud our presidents for the money they raise. But is the way we do things still working? After all, the reason we value our institutions is for what they allow students and faculty to accomplish. Their preservation is not the end. They are the means to serve the public through education and discovery.

There is a freedom in philanthropy that is provided by no other source of revenue. There are few constraints on how it can be solicited and how it can be given. Philanthropy, rightly understood, is also core to the promise of higher education as it asks the fundamental question of purpose. But since it has become routinized, often in beneficial ways combined in the art and science of advancement, we tend to focus more on performance in terms of attracting dollars rather than the more fundamental question of whether we are soliciting philanthropy for the right priorities. Unlike tuition and government support that must meet the requirements of accreditors and regulators, philanthropy provides the freedom and the

choice to decide what our fundamental priorities are. We cannot let ourselves become distracted by the process. We should ask if the philanthropy being raised for the priorities we articulate continues to suit the underlying purposes we serve for the public good.

Readers of these pages will have a close affinity to at least one institution of higher education, and they may give to it because of what the institution gave them or enabled them to become. Hopefully, such self-regard will have within it a consideration for the public contributions one’s education made possible. The instinct to enable others to receive such an experience reveals a commitment to others—a public spirit.

Contemporary Trends and Patterns of Giving

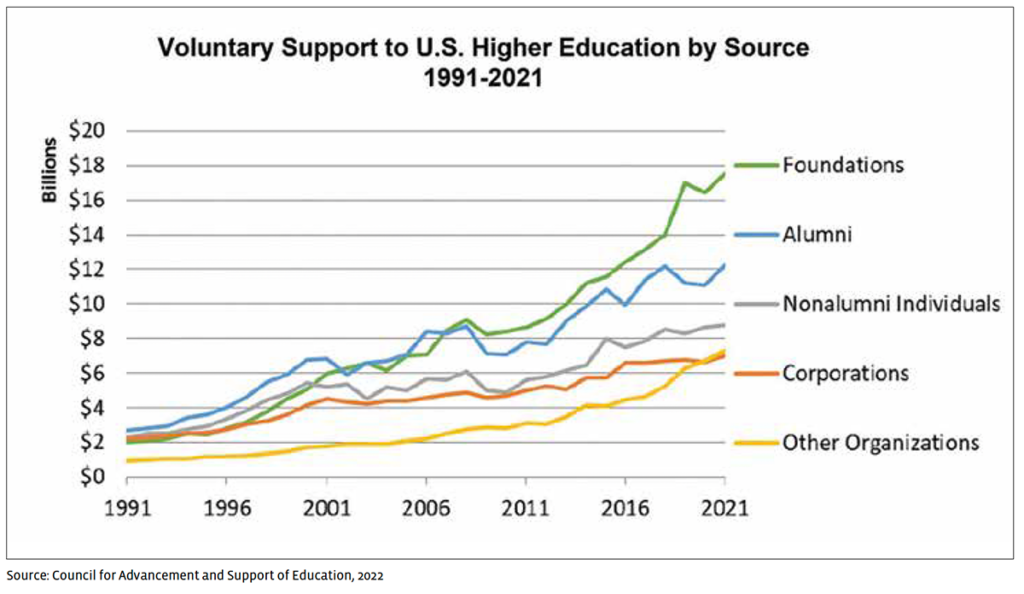

To ask relevant questions and provide sound guidance, it helps to recall the basics about recent trends and patterns of giving to higher education. Even though a handful of higher education institutions have some of the largest endowments in the world and have recently been attracting occasional gifts at the billion-dollar level, religion is still the cause that attracts most giving from Americans. According to the annual Giving USA report published by the Giving Institute and researched by the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, of the $484 billion Americans gave to charity in 2021, the second-most went to education, the majority to higher education.[3] The Council for the Advancement and Support of Education (CASE) estimates that in the fiscal year ending June 2022, $59.5 billion went to higher education institutions. The important note to remember is the dominant role of individuals in American philanthropy even though corporations and foundations receive much of the media attention. Sixty-seven percent of all giving in 2021 came from individuals and another nine percent came from bequests that are also directed by individuals.

The pattern of giving to higher education also differs in comparison to other causes because foundations play a larger role. However, the line in the graph above overstates the role of professionally staffed foundations like Ford, Rockefeller, Carnegie, and Gates. There are more than 100,000 foundations in America—half being family foundations—and most of them don’t employ any staff. Their giving decisions are more akin to those made by individuals.[4] Still, if you combine alumni and nonalumni individuals, which includes trustees, you still see that individual giving decisions are pivotal for higher education. Moreover, the growth in “other organizations” reflects the increase in funds that come from donor-advised funds, most of which reflect individual giving.

Also, important to note is the concentration of philanthropy. The 100 private and public universities that receive the most philanthropy consistently receive more than one-half of all giving to higher education.[5] One of the most widely shared concerns at our workshop was that the institutions through which most Americans experience higher education—community colleges—receive a very small portion of our country’s monetary generosity, despite some more recent attention, including from MacKenzie Scott.[6]

Reflecting an increasing focus on impact by more donors who want to see specific outcomes from their philanthropic investment, research by my colleagues at Indiana University shows that much of the growth in giving over the past three decades has gone to restricted purposes.[7] The amount of unrestricted funding given to be used at the discretion of leadership has remained flat. Still, university leaders have full discretion in crafting the kind of targeted proposals with clear outcomes that appeal to donors. Restricted purposes such as scholarships and professorships are likely to be relevant for the very long term, and gift agreements can be drafted in ways to make sure that future generations are not beholden to purposes that will be irrelevant to their circumstances. The creative college leader, in tandem with capable advancement staff, can think ahead carefully about the kinds of allocations for how a focused, restricted gift would be used, thus focusing creative energy at the point of designing the solicitation.

Institutional discretion has moved from deciding how to allocate gift funds to how to solicit them. There is no point in bemoaning the trend of donors wishing to be more focused and informed of the expected outcomes of their gifts. Research shows that donors who are presented with specific options through carefully cultivated institutional relationships tend to give more and bigger gifts.[8]

Decreasing donor and alumni participation is also a concern. More giving is coming from a smaller number of donors, and that is reflected also in declining alumni participation rates across higher education, especially among younger alumni.[9] This leads to a worry about the pipeline of future donors. Also, a smaller number of wealthy donors could have even more leverage on higher education institutions. Their influence would depend in part on how adept institutional leaders are in convincing donors to adopt the institution’s priorities.

With the rise in restricted giving and the increasing prominence of a relatively small number of wealthy donors, the creativity and persuasiveness of leaders in crafting strategic solicitations is critical. One way to look at the continuum of giving to higher education is to see individual donors as relatively open to an institution’s conception of the public good that giving can be designed to accomplish. On the other end of the spectrum are private foundations that tend to have more well-developed ideas about what they want to accomplish, which higher education institutions must accommodate. Especially as we consider the public good that higher education seeks to achieve, foundations continue to play a vital role.

Foundations

Compared to major gifts from individuals and families, private foundations with professional staffs are much less malleable and flexible in being able to tailor their grants to the specific ambitions of institutions. But foundations often have a reputational benefit to confer. Institutions rightly boast about a name-brand foundation grant to a faculty member, a center, or a program, as these have often been peer-reviewed, vetted by internationally known experts, and found promising in a competitive process. Prestige is attached to funding from the Howard Hughes, Mellon, or MacArthur foundations and it signals a level of excellence and recognition that appeals to a range of constituencies.

It is rare for individual major gift donors to engage in calls for proposals and consider entities or researchers in open proposal processes, inviting applications from those with whom they do not have a previous relationship.[10]

Furthermore, conscientious foundations will feel an obligation to justify how they pursue the public good to compensate for their lack of accountability. Since they don’t answer to voters, clients, donors, or investors, they are set up to formulate their own conception of the public good, so they take some care in making a strong case for themselves.

The impact of foundation funding exceeds the money they grant because they also help define the purposes of higher education and act with a degree of social authority that stems from their close historical association with higher education, their involvement in policy deliberations, and their connections to social elites. They have helped articulate our current understanding of the purpose of higher education as our collective effort to bring people in from the margins of society—a collective effort that is embraced by thousands of institutions that occupy America’s diverse higher education landscape.

This expectation was importantly nurtured by a handful of highly engaged private foundations that focus on the growing need for college-educated talent across our society—at the same time as we have been failing to provide equitable access to this increasingly important pathway to social mobility.

Another source of private foundation influence is the fact that they are kindred spirits of colleges and universities. Devoted to applying advanced knowledge, often led and staffed by experts, they have boards that help guide them in their pursuit of the public good. Today foundations and universities are often united in the project to expand access and success beyond the current populations who benefit from higher education.

There have also been broader trends that foundations have promoted with important consequences for higher education. The Kresge Foundation was known for supporting capital campaign

projects across much of higher education in the latter decades of the 20th century. It was the go-to destination for colleges seeking to fund a new building. As part of the application process, colleges had to demonstrate that their trustees had bought into and donated to the campaign that would be anchored by a Kresge contribution. More recently, Kresge has joined foundations such as Lumina, Gates, Strada, ECMC, and Ascendium in promoting greater access to higher education for previously under-served populations. In this evolution of one prominent grantmaker, you see a move from strengthening institutions through a system of resource acquisition focused on capital to one focused on expanding access and driving equitable outcomes for students from across diverse populations.

Foundations also play a role in helping to shape substantive trends within the academy. For example, the Mellon Foundation has been a stalwart proponent of the arts and humanities in higher education for decades. Even as it has moved to address inequities and injustices, it is doing so through the arts and humanities. Few individual donors can have the kind of ecosystem-wide influence that is made possible by the institutional form of the private foundation.

One of our workshop participants, Andrea Walton, has written a masterful review essay on the history of philanthropy in higher education, including the vital role foundations play in advancing policy discussions. In the 20th century, Rockefeller and Carnegie had key roles in reforming medical education, generating the eponymous Carnegie Classifications, and formulating what became the Pell Grants.[11] The collection of higher education associations that represent different segments of the higher education ecosystem in Washington, D.C., also arose with foundation funding.

Today, foundations engage policymakers in expanding the success of historically underserved populations, engaging in discussions at the state and local levels in addition to the federal level. There may be an opportunity for many more institutions to engage in such policy conversations in imaginative ways. But this requires seeing each institution as less of an island and more a piece of the puzzle we call the public good, philanthropy serving as a common thread in enabling its pursuit.

What Should Higher Education Philanthropy Focus On?

Given the responsibility of philanthropy to engage with higher education for the public good, the following themes were brought up during the workshop as priorities for philanthropy in higher education:

- Broadening access and success—the broader inclusion agenda that is evident in many foundation priorities and in at least the declarative strategies of most colleges and universities.

- Focusing on existential threats such as climate change is an area with dramatic impact on the public good.

- Protecting democracy itself. It is vulnerable to the polarization and specialization that divide us. Can we preserve or create room for common learning?

- Advancing understanding of the good life and the good society are based in deeper values that philanthropy and higher education can pursue together.

- Addressing questions of why? Colleges prepare our emerging generation for careers and citizenship, but what is the purpose of these in the future?

- Addressing Issues of mental health, loneliness, isolation, and the loss of community.[12] Colleges and philanthropy could help rebuild communal ties.

- Restoring trust in knowledge and science.

- Fostering collaboration across institutions and combatting institutional self-interest and inertia.

- Assuring quality and accountability of institutions so that opening doors more widely leads to quality outcomes for all. Addressing affordability that continues to be a significant barrier to access and success.

- Exploring credentials and novel alternatives more systematically in a context of rapid and confusing growth in noncredit certificates and credentials.

- Fixing a failing business model for higher education, including facilitating institutional mergers and sunsets.

- Considering the evolving role of faculty in new business models for higher education.

- Adopting an orientation of transformative urgency to innovate boldly.

- Connecting research to policy—the disconnects between these communities are limiting what can be done. All the brain power in academe focused on these issues could add more value, and it seeks to add more value.

Once inside an institution as a dean, provost, president, or board member it is natural to advocate for more resources to advance the institutional mission. But because philanthropy is neither a government-regulated stream of funding nor a fee, like tuition provided in exchange for a service, philanthropy represents an opportunity to innovate, educate, and discover in novel ways.

Advancement staff will know how to engage the newest forms of giving and work to align the institution’s needs to the interests of donors. Trustees should ask leadership to be clear on priorities and whether the institution is taking advantage of the full range of possible openness there may be in crafting a joint vision with a donor. Also, trustees themselves are often key donors or can play important roles in cultivating and soliciting major donors.

The funding interests of donors, even the systematically generated programs of expert-staffed foundations, are not fixed in stone. They are open to influence and adaptation by compelling arguments for the public good. Indeed, one of the justifications for giving private wealth a role in engaging the public good in a democracy is to foster pluralism. We allow and even celebrate a plurality of conceptions of the public good. And what institutions are better constituted to engage in this kind of deliberation amidst plural visions of the public good than colleges and universities?

Nurturing the Moral Imagination

One inspiring vision of philanthropy sees it as the social history of the moral imagination, reflecting the ability we all have to imagine a better future with others.[13] At the workshop, we assembled funders, practitioners, and scholars who rarely deliberate together using their moral imagination to work toward a better reality. Our participants, who work at the intersection of philanthropy and higher education, gathered to consider whether building connections across the different kinds of work we do could lead to better service to the public.

It is as if we assembled a group of trustees for a venture that was yet to be established but for which there was a perceived need and for which there was a shared commitment. We had

foundations, think tanks, former and current college presidents, association leaders, scholars, and consultants engage each other’s perspectives, sharing their concerns and ambitions for the future of philanthropy in higher education.

One important instinct that was affirmed at the workshop was that presidents, chancellors, and trustees, just like donors and foundation officials, rarely have the time to benefit from the vast amount of scholarship on higher education, especially the often-overlooked field that looks at the role of philanthropy in higher education. There are not enough bridges to allow the insights of researchers to travel to those who could use them. Nor are there enough opportunities for researchers to hear from those leading in practice, so that research is animated by more relevant questions.

Too much talent involved in leading and advising higher education institutions remains disconnected from the talent that does research on institutions and the ecosystems in which they operate. Think of the possibilities if presidents and trustees could marshal the talent of the scholars and researchers who are eager to produce research that serves the public good.

What is needed is not a one-time connection, but a lasting community of engagement that will allow for research to better inform practice. This is what we hope to have begun with our workshop.

Philanthropic funders are ultimately unaccountable, within the limits of the law, except to their own articulation of the public good. They have the most freedom to deploy resources, to pursue their understanding of the public good. They end up spending a good bit of time articulating how they think their efforts are serving us well, but they rarely have the capacity to critically examine the intended and unintended consequences of their work. This is where scholars and researchers can look to the past and present and hold them accountable not only to their own professed purposes but also to the mores and norms of the public at large. Finally, practitioners who run or support educational institutions can let scholars know how useful their work is to practice.

Furthermore, there is value in occasionally creating communities that think and work outside the grooves of established institutions or ways of doing business. Over time, all institutions develop interests and habits that may not be aligned with what is best for the public they aim to serve. There are many historical examples of institutions that were extinguished or radically transformed because they were no longer relevant. That is not to say that our colleges and universities are approaching obsolescence. But not asking the question of relevance is likely a good recipe for becoming more removed from the needs of the times. I see the workshop as being a process of asking this question.

Higher education is composed of a wondrous, multifaceted, diversity of institutions that serve different kinds of publics with different views of how to express and pursue the public good. It is also clear that they are faring differently in the current environment and that philanthropy writ large does not engage equally with all kinds of institutions. Critiques of this situation have become more pronounced as we have seen $100 million and even billion-dollar gifts, at a time when the institutions through which most Americans experience higher education—community colleges—prior to the pandemic had an average endowment of $12 million.[14]

Going forward, the community we assembled will look to continue the conversation on how philanthropy and higher education can better serve the public good, turning to focus on a few of the pressing questions we identified. We hope to have an open conversation and invite others to participate, realizing that deliberating in a small workshop setting allows for a kind of candor and learning that is hard to replicate when we are online, or in larger groups. We welcome feedback and engagement as we look forward to asking the fundamental question of how philanthropy and higher education can better advance the public good.

Questions Board Members Can Ask

■ Consider your giving to your institution—what is it achieving?

- How is it advancing the public good?

- Is it informing paths toward needed reform or transformation?

- Is it addressing current and emerging crises?

- Could philanthropy be redeployed toward more impact on campus and in the community?

- Are there opportunities to engage philanthropy to forge new ideas and partnerships?

- Do your strategic plan and your comprehensive campaign reflect your core public purpose? How will philanthropy make a decisive difference? Do your plans include natural collaborations to reflect the scope of the challenges being addressed?

■ How is your college or university engaging the big questions about individual, community, and national purpose? Who is it joining in doing so?

■ Are you taking advantage of all the ways in which philanthropy can advance your institution?

- What activities must be sustained, and which ones are fulfilling purposes that can be better achieved by others?

■ What is the moral imagination that animates your community and what is your role in nurturing it?

■ How can I help make philanthropy more relevant and effective?

Amir Pasic, PhD, is the Eugene R. Tempel Dean of the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, the world’s first school devoted to research and teaching about philanthropy.

Endnotes

1. Anthony P. Carnevale, Tamara Jayasundera, and Artem Gulish, America’s Divided Recovery: College Haves and Have-Nots, Georgetown University McCourt School of Public Policy Center on Education and the Workforce, 2016, https://cewgeorgetown.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/Americas-Divided-Recovery-web.pdf.

2. Malcolm Gladwell, “My Little Hundred Million,” July 21, 2016, in Revisionist History, podcast, https://www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/revisionist-history/my-little-hundredmillion; Anand Giridharadas, Winners Take All: the Elite Charade of Changing the World (New York: Penguin Random House LLC, 2018); Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018); Edgar Villanueva, Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance (Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc., 2018).

3. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, Giving USA: The Annual Report on Philanthropy for the Year 2021, (Chicago: Giving USA Foundation, 2022).

4. Avrum Lapin, “Foundations that Act Like Individuals: Family Foundations Explored,” Member Insights (blog), The Giving Institute, April 12, 2017, https://www.givinginstitute.org/news/340261/Foundations-That-Act-Like-Individuals-Family-Foundations-Explored.htm.

5. Council for Advancement and Support of Education, “Philanthropy’s Role in the Future of Higher Education: Data to Inform Participant Conversations,” (Special report from the CASE Voluntary Support of Education Survey, A Workshop on Higher Education and Philanthropy: Philanthropy’s Role in the Future of Higher Education, Indianapolis, IN, December 1, 2022); Ann E. Kaplan, Voluntary Support of Education 2021, Council for Advancement and Support of Education, April 2022, 26, https://www.case.org/resources/vse-summary-findings-2021.

6. Ibid.

7. Shaker, G. G., and Borden, V. M. H., “Analyzing Three Decades of Philanthropic Giving to U.S. Higher Education (1988–2018),” Philanthropy & Education 4, no. 1 (Fall 2020): 14, https://doi.org/10.2979/phileduc.4.1.01.

8. Cara Giacomini, Deborah Trumble, Anna Koranteng, and Jacqueline King, CASE Study of Principal Gifts to U.S. Colleges & Universities, Council for Advancement and Support of Education, June 2022, 29, https://www.case.org/system/files/media/file/CASEStudyofPrincipalGifts_finalrevised6.21.22_2.pdf; Una Osili, Chelsea Clark, and Jon Bergdoll, The 2021 Bank of America Study of Philanthropy: Charitable Giving by Affluent Households, Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, September 2021, 50, https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/1805/26654/bank-america-sept21.pdf; Leaving a Legacy: A New Look at Today’s Planned Giving Donors, Giving USA Foundation, 2019, 57, https://givingusa.org/just-released-special-report-leaving-a-legacy-a-new-look-at-planned-giving-donors/.

9. Council for the Advancement and Support of Education, Voluntary Support of Education: Trends in Alumni Giving, April 2019, 9, https://www.case.org/system/files/media/file/Alumni%20Giving%20April%202019_8-16-19.pdf.

10. The prominent Effective Altruism movement is an exception. See Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 149-150.

11. Andrea Walton, “The History of Philanthropy in Higher Education: A Distinctively Discontinuous Literature,” Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research 34, (2019): 499-500, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03457-3_11

12. The Chronicle of Higher Education, Mental Well-Being in the Covid Era: Students Are Struggling. How are Colleges Trying to Help?, 2021, https://connect.chronicle.com/rs/931-EKA-218/images/CampusWellBeingInTheCovidEra.pdf

13. Robert L. Payton and Michael P. Moody, Understanding Philanthropy: Its Meaning and Mission, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008).

14. Ed Finkel, “Endowments: They’re Not Just for Elite Universities Anymore,” Community College Daily, American Association of Community Colleges, November 11, 2019, http://www.ccdaily.com/2019/11/endowments-theyre-not-just-for-eliteuniversities-anymore/.

RELATED RESOURCES

![]()

Reports and Statements

Collaborative Leadership for Higher Education Business Model Vitality

Webinar On Demand

Investment Governance for the Post-Pandemic World