The ivory tower simply isn’t what it used to be. Long gone are the days when academics, the administration, and even the board could simply focus on intellectual, philosophical, and esoteric pursuits happily disconnected from the rest of the world. In fact, colleges and universities have never been under as much external scrutiny as they are today, and expectations—and criticism—have never been higher.

By their very nature, institutes of higher education are often at the crossroads of a variety of uniquely difficult issues, but over the past few years we’ve reached a critical juncture where both the industry as a whole and individual institutions are smack in the crosshairs of the public and of policymakers.

This can be attributed to three key factors:

An Institutional Trust Deficit: Trust in virtually every formal institution of power—government, business, religion, and the media—is at an all-time low. Ironically, academia is considered a relative bright spot, but that halo of trust applies only to individual professors and certainly not to “the administration.”

An Industry Under Fire: Whether due to broad questions about affordability, accessibility, or the decline in support for the idea of higher education as a “public good,” these broad “industry” challenges are exacerbated by poorly managed crises including sexual assaults, protests, natural disasters, and data breaches, as well as a range of self-inflicted social, financial, and ethical issues including admissions and rankings scandals.

The Changing Nature of Traditional and Social Media: In an environment in which vitriol and conspiracy theories abound and polarized media reduces everything to polemic, colleges and universities that need to explain their positions and actions face an uphill battle. When the news is more about finding facts that support existing values or positions, both the challenges of protecting an institution’s reputation and the importance of doing so becomes that much greater.

Protecting Your Institution: Understanding the Risk

Protecting your college or university rests on a proper understanding of reputational risk. This risk, which occurs when there is a significant disconnect between an institution’s decisions and the expectations of its stakeholders is highest during a crisis. However, left unaddressed, slowly evolving and slow-moving issues can be as corrosive over time as any crisis and result in potential long-term and sometimes unrecoverable damage.

Unfortunately, due to the nebulous quality of reputation, very little attention is given to the subject itself, to what drives it, or to what contribution it makes to the school’s success and long-term viability. But given that reputation is arguably a school’s most valuable intangible asset, reputational risk must be taken as seriously and managed as diligently as financial and legal risk.

As board members, you play a key oversight role. If your institution is to move from passive acceptance of reputational risk to proactive management, you must, at minimum, understand the following:

- Who at our institution is responsible for reputational risk?

- How prepared are we to manage that risk?

- What role should we, as a board, play during a crisis?

Question #1: Who is Responsible for Managing Reputational Risk?

When you ask this question, don’t be surprised if you’re met with blank looks. At most institutions, there is no defined program, budget, or staff. And forget about KPIs. Rarely are there objectives or criteria to understand or measure reputational risk from one year to the next. But if it is no one’s responsibility—or perhaps added nonchalantly to the president’s list of things to worry about—is it any surprise that it is not proactively managed?

The one exception is when reputational risk, erroneously viewed as a component of “brand,” is delegated to the “comms” team. But reputation is not the same as brand. Whereas brand is stated, reputation is earned. It is the complete picture of your institution built up over decades, if not centuries. It is based on the actions and behaviors of every person—past and present—associated with your school. As such, reputational risk—while dependent on the critical component of communications in its management—is not fundamentally a communications challenge.

Reputational risk is a strategic risk that can only be mitigated when it is integrated with the broader strategy of the institution, reflective of institutional values, and driving a culture in which reputational risk is proactively identified, mitigated, and managed.

How to Ensure Reputational Risk is Identified, Monitored, and Addressed:

- Assign responsibility: effective champions for a reputational risk management program include the chief risk officer, chief communications officer, or chief officer, chief communications officer, or chief of staff.

- Insist on regular board updates around emerging areas of reputational risk.

- Ensure that reputational risks are systematically discussed and addressed.

Not unlike your finance or litigation update process, reputational risk monitoring and reporting provides information, perspective, and confidence that the internal team is on top of key developments.

Question #2: How Prepared Are We to Manage Reputational Risk?

In most corporations the distinction between crisis management—strategy, decision-making, reputational risk—and emergency management—operational, life/safety, physical events—is clear and understood. In higher education, however, an overemphasis on emergency management following the tragic shooting at Virginia Tech has created a false sense that colleges and universities have a “crisis management” capability in place—when in fact they do not.

When there are insufficient management tools, methodology, or even language to describe what needs to be in place in order to manage and mitigate reputational risk, is it a surprise that at most institutions that there is a limited ability to do so?

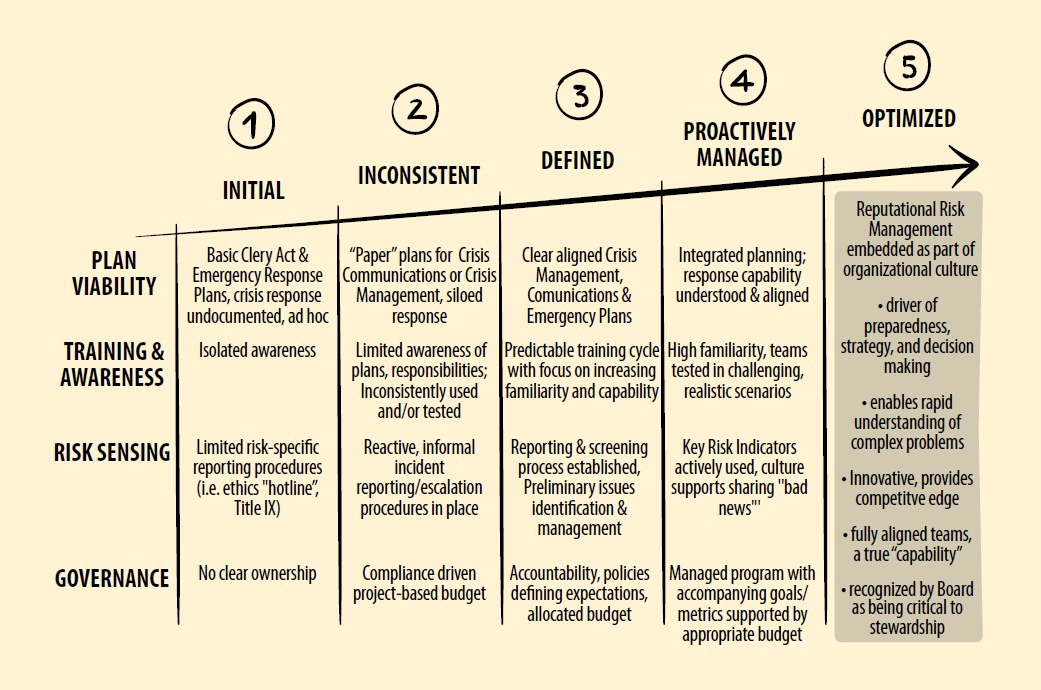

The following is our firm’s Reputational Risk Maturity Model. It builds and adapts the Carnegie Mellon model developed to assess the effectiveness, capability, and areas for improvement of processes especially relative to software.

In this version, an institution’s capability to manage reputational risk is assessed against four criteria: risk sensing, plan viability, training and awareness, and governance. We find that most universities fall somewhere between level 1 and 2 and unfortunately, they frequently they languish there. (See chart below.)

How to Ensure that Your Institution is Prepared to Manage Reputational Risk:

- Ensure that there is a plan, team, and capability to manage reputational crises at your Emergency management plans are almost always insufficient as they are wholly inappropriate to address or completely silent on the “self-inflicted” crises that make up the 90 percent of crises your school will face.

- Assign responsibility and fund your program! If there is no budget and no one is responsible, it’s highly likely that the institution’s level of risk is unacceptable. Spending on reputational risk management is an investment in the same way a hedge or derivative is used to protect the value of the underlying asset.

Question #3: What is the Role of the Board during a Crisis?

If satisfactory answers are not available to the questions above, it is unlikely the leadership team will be able to define the role of the board during a crisis. But this information is critical to know and understand before an event because it’s an organizations response to crisis, not the underlying event, that has the biggest impact on reputation. Managed poorly and the response is going to be remembered and the reputational damage significant. Managed well, the reputation of the organization and its leadership can be burnished.

A board’s fundamental roles are to:

- ensure the financial sustainability of the institution,

- ensure a sound strategic direction; and

- appoint an effective leader.

A crisis will often impact all three of these objectives, and frequently the board will either become directly involved in the institutional response to the crisis or may end up being blamed for the crisis.

How to Ensure the Appropriate Board Role:

- Establish a clearly defined coordination process between the administration and the board during a crisis. This should include:

- Prompt notification any time the Crisis Management Team (CMT) has been activated

- Clarity on what information is shared with the executive committee versus what is shared with the broader board membership—confidentiality is a key consideration particularly in “self-inflicted” crises

- A focus not just on the facts as known but the forecasted impacts and consequences of the reputational, legal, operational, and financial risk created by the crisis

- Identification of specific, significant decisions reserved for the board’s Executive Committee

Formalizing this process can help build confidence among board members that the crisis is being appropriately managed while maintaining the administration CMT’s authority to make decisions effectively and expeditiously.

We know that a strong reputation leads to high-quality faculty, the recruitment of a dynamic student body, supportive and active alumni, a competitive edge in research and grants, as well as the support of local communities and government authorities. As a result, across the country and around the world boards and administrators have supported increasingly sophisticated and expensive branding campaigns in order to help differentiate their institutions in a competitive marketplace. Yet all of this work, time, and money spent on brand building, has the potential to be completely undone by one major issue or crisis.

In closing, I leave you with a well-known quote from Warren Buffet, the business “Sage of Omaha” who reminds us that “It takes 20 years to build a reputation and 5 minutes to ruin it. If you think about that, you’ll do things differently.”

Simon Barker is the managing partner of Blue Moon Consulting Group (BMCG), a crisis management firm that specializes in higher education. He’s supported school leadership in their response to protests, academic scandal, sexual assault, natural disasters, data breaches, and workplace violence along with a range of social, financial, and ethical issues. Barker’s book, Preventing Crisis at Your University: The Playbook for Protecting Your Institution’s Reputation, is available from Johns Hopkins University Press.