- Foster a system of shared governance that moves the institution from constituency based thinking to institutional thinking

- Develop a common understanding of what effective shared governance is and what it is not

- Ensure that every board member is familiar with the AAUP “Statement of Government of Colleges and Universities”

- Commit to a culture of transparency. Share information early to create deep discussion and iterative decision-making

- Be clear about the parameters of the decision-making process and communicate about the need for timely decisions.

Does shared governance promote nimbleness for institutions of higher education or is it an impediment? Is shared governance a tool for creating the alignment necessary for transformational change or is it a cumbersome relic that stands in the way of bold decision-making? Debates like these are increasingly common in college and university boardrooms. Most trustees are committed to the general principle of shared governance but also wonder whether traditional systems of shared governance are still relevant in times of rapid change.

From my experience in consulting with dozens of colleges and universities over the past ten years, I have seen, firsthand, that shared governance, when properly conceived, structured, and fostered, is an effective engine of change to help colleges and universities with institutional thriving. Trustees have a central role to play in setting the stage for effective shared governance and holding institutional leaders accountable for fostering a system of shared governance that advances the institution’s mission.

The best practices described in this article enable boards and their institutions to utilize shared governance as a powerful tool for institutional sustainability and thriving.

A central challenge for leaders is how to foster a system of shared governance that moves the institution from constituency-based thinking to institutional thinking. Constituency-based thinking is marked by who owns what decision, how decisions can be made to benefit my group, and how to exclude other groups from interfering with those decisions. It often includes short-term thinking, resistance to change, and efforts to preserve the status quo. A prime example of constituency-based thinking is a faculty that will not approve new academic programs because faculty members believe new programs will draw resources from existing programs. Institutional thinking is marked by a willingness to place the mission and well-being of the institution above individual interests. It fosters strategic thinking, high levels of teamwork, and iterative decision-making (changing decisions tentatively made based on the reasoned input of others).

Fear creates fertile ground for self-preservation and constituency-based thinking. And these are fearful times in higher education, when finances are tight for many institutions, competitive pressures mount, and changing conditions necessitate prompt decision-making. But shared governance, when properly conceived and well tended, can help align faculty, administrators, and boards and help them to think institutionally. Effective shared governance—which can focus on who owns what—when carefully tended can move to shared responsibility through which all parties feel accountable for decisions made and the future of the institution.

A primary responsibility for ensuring that shared governance is effective lies with the board. Boards have heightened responsibilities in times of rapid change and new opportunities, which are more easily fulfilled with well-defined and well-tended shared governance:

- The board must lead its institution in understanding the challenges facing higher education and the evolving opportunities, as well as accurately assessing the institution’s capacity to be nimble enough to confront challenges and seize opportunities.

- The board must lead the institution in developing realistic, achievable strategic plans for sustainability and prosperity that are understood and supported by trustees, administrators, and faculty leaders.

- The board should insist that the administration, with the input of faculty, is developing metrics to evaluate institutional sustainability and performance.

- The board should tend shared governance to foster the alignment necessary for all constituencies of the institution to invest their time and efforts into sustainability and excellence.

For most institutions, it will be impossible to fulfill the first three responsibilities without the effective shared governance described in the fourth.

Defining Shared Governance

If trustees, administrators, and faculty members define shared governance in different ways, they will find it ineffective. It’s important for institutions to develop a common understanding of what effective shared governance is and what it is not.

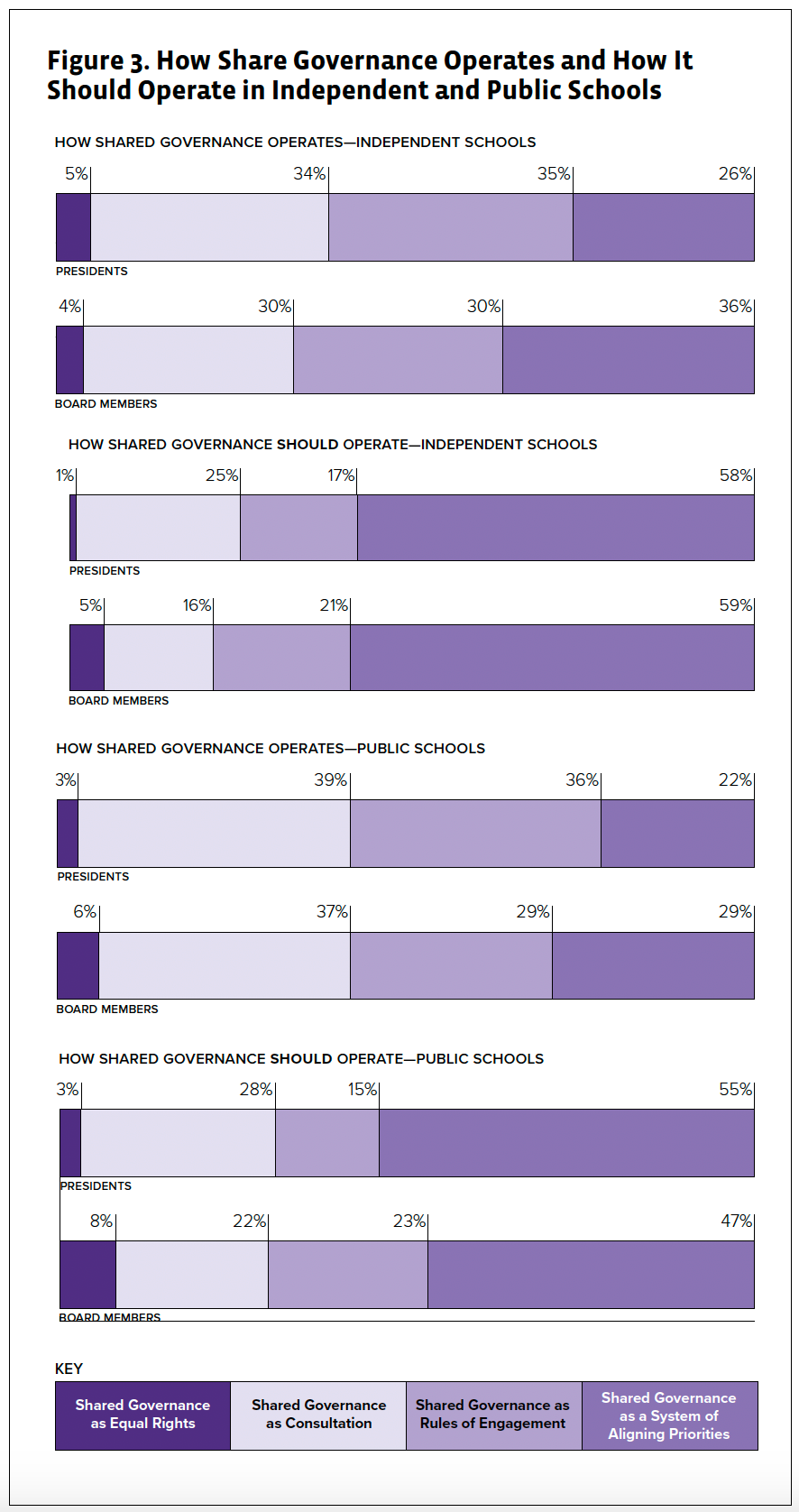

The following traditional definitions of shared governance fail to foster the nimble and timely decision-making needed today for colleges and universities:

- Shared governance as equal rights to governance.

- Shared governance as an obligation to consult before making important decisions.

- Shared governance as rules of engagement between board, administration, and faculty.

- None of these definitions of shared governance adequately facilitates agility and bold decision-making. Nor do these definitions facilitate moving from constituency-based thinking to institutional thinking.

When shared governance is viewed as equal rights to governance, decisions can’t be made until a consensus is reached by all. With this definition, faculty essentially have a veto right over decisions. Giving faculty a veto over major decisions is an abrogation of the board’s fiduciary duty to make decisions that are best for the institution, not just one constituency. Further, decisions made by consensus tend to be political, aimed at satisfying all parties by seeking the least common denominator. Rarely are such decisions bold. Structuring the endless committees and faculty processes to achieve consensus risks slow decision-making, often finalized after the engine has left the station.

Many trustees would define shared governance as the obligation to consult before making important decisions. While consultation is an indispensable part of shared governance, consultation with impacted stakeholders is not, alone, sufficient for effective shared governance. Too often the consultative process is engaged in too late, after decisions have been effectively made. At other times, mere consultation does not result in an iterative decision-making process, with those consulted feeling that their views were fairly considered. And too often, faculty are consulted on important matters, but their input is dismissed because the board sees it as uninformed. When faculty input is indeed uninformed, it’s likely because faculty have not been provided sufficient background and information about the decisions to be made. In sum, too often faculty see “consultation” as pro forma.

Perhaps the most common definition of shared governance in American higher education is as a set of rules of engagement. Rules of engagement identify who has primary responsibility for various decisions and how responsibilities are carried out when they overlap. Most faculty handbooks embody this approach by defining decisions made by the faculty, and, often, seeking to minimize administrative engagement in those decisions.

Those viewing shared governance as rules of engagement often turn to the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) “Statement of Government of Colleges and Universities” to identify responsibilities and rules of engagement between faculty, administrations, and boards. This statement was adopted by the AAUP in 1966 and commended by AGB to its members at that time. The statement seeks to assign primary authority to those closest to the decision and with the greatest expertise: faculty for academic matters, administrators for budgeting and planning, and board members for exercising their fiduciary authority. Some board members are inclined to dismiss the AAUP as an “advocate for faculty” and not the entire institution. But those who study the AAUP statement carefully recognize that it is well balanced, seeking to empower all through time-tested norms of higher education that provide that those with most expertise about a decision should have primary responsibility. And it’s important to note that the AAUP principles firmly acknowledge that the board has the ultimate fiduciary and decision-making authority over the institution.

The AAUP statement does help inform the parameters of shared governance, but it’s not sufficient to provide a full blueprint for moving away from constituency-based thinking. Rules of engagement build fences. During these challenging times in higher education it’s not true that good fences make good neighbors. Fences serve to divide and discourage collaboration. What is needed in higher education are decision-making processes that enable nimble, timely, and shared decisions.

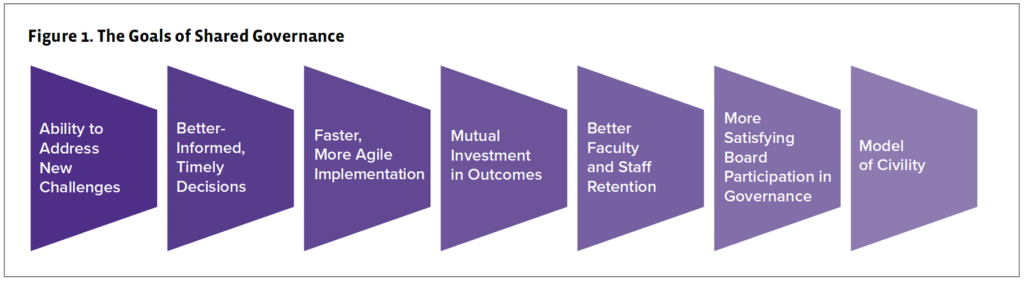

Shared governance, then, is best crafted as a process of decision- making designed to align priorities. When priorities are aligned between the board, administration, and faculty, decision-making will be more nimble, timely, and bold, and less constituency-based because each constituency is invested in identifying and pursuing mission-driven outcomes and priorities. This ideal of shared governance has these five components:

- culture of transparency and open communication;

- commitment to jointly consider difficult issues and jointly develop strategic directions;

- system to make timely decisions to support agility and timely action;

- shared set of metrics for success; and

- system of effective checks and balances to ensure that the institution remains mission focused.

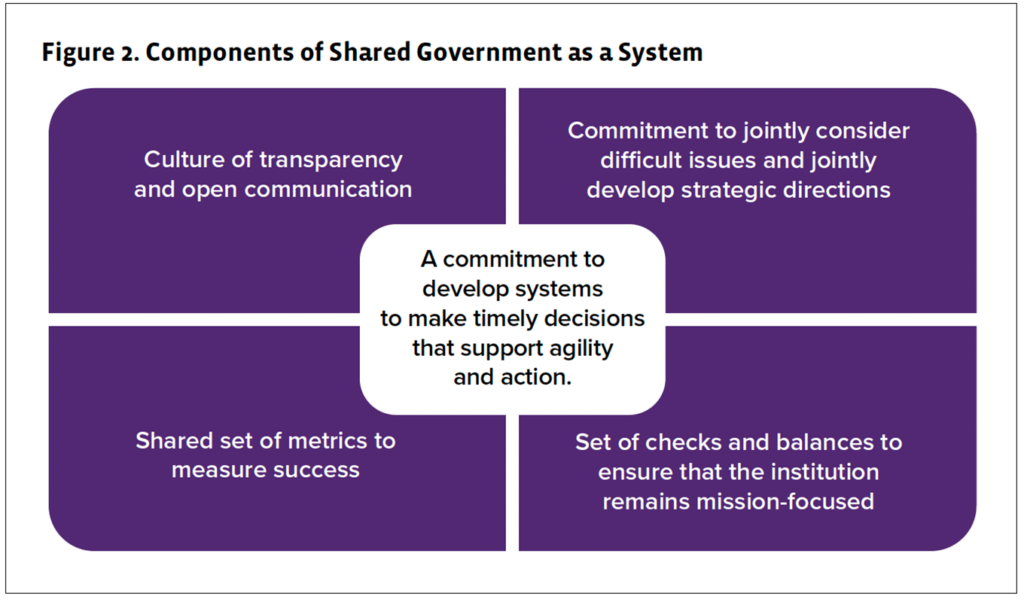

A culture of transparency exists when the board, faculty, and administration engage in effective three-way communication. Transparency is more than sharing information at the last minute, as an afterthought or with the intent of merely fulfilling an unwanted obligation before a decision is made. Deep transparency means sharing information early, in a way that is understandable and that creates the deep discussion necessary for iterative decision-making.

When sharing information with faculty, a culture of transparency involves a culture of respect, recognizing that each constituency in higher education can add value to decision-making. In my 19 years as president of Augustana College in Illinois, the faculty, board, and administration worked together to develop dozens of new programs to keep enrollment robust. Often, the administration would start the process by asking the faculty to consider a possible new program. We would typically outline what the new program might look like. Invariably, because the faculty felt respected and saw shared governance as shared responsibility, faculty members tapped into their considerable program-design expertise, modifying the initial outline into an even stronger program. Because of the deep faculty engagement, programs were high-quality programs, easily approved by the faculty and seamlessly implemented.

Committing to jointly consider difficult issues is a key ingredient of effective decision-making. High-quality decisions in higher education are usually the result of the “marketplace of ideas” where different perspectives are examined and the best ideas gain endorsement by all. While resolution of deeply contested major issues may be ultimately decided by the board, faculty most often add significant value, particularly when they view governance not merely as a set of boundaries, but also as an obligation of thoughtful shared responsibility.

A commitment to timely and agile decision-making is an increasingly important component of shared governance that is missing at too many institutions. Decision-making that is not timely will be “a day late and a dollar short.” Critical to timely and agile decision-making is to move from cumbersome constituency-based decision making to decision-making that supports the institution.

Effectively considering difficult issues facing the institution and developing strategies to address those issues is only the first step. As important is committing to develop a shared set of metrics for success to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies and pave the way for continual review of strategies and improving tactics in a timely way.

Finally, shared governance cannot be effective at most institutions without a system of effective checks and balances to ensure that the institution remains mission focused. These checks and balances include a clear understanding of how decisions are made, what role each constituency has in the decision-making process (for example, consultive, preliminary decision-maker, final decision-maker) and how differing points of view are addressed and considered. Many of these checks and balances are found in charter documents for the institution and in the faculty handbook. The AAUP “Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities” also provides helpful guidance.

Trustees can help move institutions to view shared governance as a system of aligning priorities by adopting a board statement asserting their support for shared governance. Board statements not only set the tone for shared governance, but they also can be useful tools in expressing respect for the faculty and the shared role of faculty in decision-making. The best board statements on shared governance have the following components:

- A statement of the board’s commitment to shared governance and a recognition of the historic importance of shared governance to the institution. This includes an expression of thanks to the faculty and administration for their commitment to shared governance.

- A statement of the board’s view of effective shared governance, crafting shared governance as a system of alignment of priorities with the five elements described above.

- A statement of the general roles of each constituency: the board as fiduciary, the president as a chief planner, and the faculty as architects of the academic program.

- A statement that shared governance fosters shared responsibility and accountability.

Some institutions have worked with faculty leadership to develop a joint statement about shared governance. While some institutions have been successful in doing so, others have not been successful because they have gotten bogged down in “what ifs” and disagree about certain granular details.

A sample board statement on shared governance can be found in my book Shared Governance for Agile Institutions: A Practical Guide for Universities and Colleges, Second Edition, AGB 2023.

Lessons learned about shared governance from the pandemic

COVID-19 hit at the heart of the overlapping responsibilities of the faculty, administration, and board. Faculty, with primary responsibility for the classroom, were concerned about safety in the classroom and the ability to provide outstanding student outcomes with a sudden shift to remote learning. Administrators and boards had similar concerns but were also focused on the budget impacts of required testing and lower enrollments, student retention, and the outcomes that any missteps could have on institutional reputation. Institutions that circumvented shared governance (and even suspended their faculty handbooks) with top-down responses experienced faculty refusing to teach, refusing to follow protocols, trashing administrative decisions with students, and even holding votes of no confidence.

Institutions that developed a response through shared governance that was widely supported took many other steps:

- Appointed and showed respect for a task force of trustees, faculty, administrators, and students to advise senior leadership and the board about the appropriate response.

- Established frequent meetings between the administration and the faculty leadership to exchange ideas and keep each other informed.

- Utilized the on-campus expertise of public health faculty, who usually had great credibility with other faculty.

- Posted for all to see the advice of local, state, and national public health officials and organizations, as well as information on the prevalence of the virus in the community and on campus.

- Committed to jointly develop with the taskforce a dashboard to monitor factors that might close the institution, open the institution to hybrid learning, or more fully open the institution.

At one college, notwithstanding that the institution took the above steps, the faculty leadership was still skeptical of the process and asked to retain its own expert. The administration consented, knowing of the fine reputation of the faculty expert. The expert endorsed the direction of the institution, but also made helpful recommendations that were integrated into the response. The participatory process led to high levels of faculty engagement and student satisfaction, as well as a renewing of the institution’s commitment to shared governance.

Five critical questions for the board to ask about shared governance

- How do board members define shared governance? Do board members agree on the definition? How do the administration and faculty define shared governance? Do the definitions align?

- Where has shared governance worked most effectively? Where has it been challenged? What lesson can be learned from where it has worked effectively and where it has not?

- Which of the ten best practices have been effectively implemented?

- In what two or three areas can shared governance be improved within the next year? Where can it be improved in the next three years?

- What strategic issues within the next year might benefit from robust shared governance in developing strategies and tactics?

Nine Best Practices in Shared Governance

Shared governance is at times messy. Trustees, faculty, and administrators are all human and occasionally stumble over the best practices in shared governance. Shared governance must be fostered and cherished, and that takes hard work.

The chances of moving from traditional notions of shared governance and constituency-based thinking to shared responsibility and institutional thinking are maximized by committing to the hard work of implementing nine best practices in shared governance.

1. Institutional leaders should emphasize to all constituencies the importance of shared governance in making timely and courageous decisions.

Shared governance must be nurtured by all leaders, including board leaders. Leaders displaying optimism about the importance of shared governance to make important institutional decisions are likely to spread that enthusiasm to other leaders.

Board leaders should periodically and explicitly state to board members, senior administrators, and faculty leaders their view that shared governance is critical to advance the institution’s mission. It may be helpful to point out that colleges and universities tend to be among the oldest of institutions in their cities or towns. One reason colleges and universities are so durable is their system of governance is less top-down and more geared toward engaging all groups through shared governance in making high-quality decisions.

Board orientations, faculty orientations, and orientations of administrators and staff should reserve time for discussions of what shared governance is and what it isn’t. These same orientations should also discuss how effective shared governance not only makes the institution strong but also makes it more satisfying and fulfilling to serve the institution.

Many institutions find it helpful for shared governance to be discussed annually at a board meeting. The board should be

reminded of what shared governance is and isn’t and how they can employ shared governance as an important tool in decision-making. A board statement on shared governance, described above, also serves as a visible reminder to the community that shared governance is important for timely decision-making.

2. The board should periodically assess the state of shared governance and develop an action plan to advance it.

Effective shared governance cannot be taken for granted. The trust necessary for shared governance can take years to build but, with missteps, can be lost in weeks. Periodically assessing the state of shared governance is critical for early detection and remedying of problems.

It’s a best practice to periodically survey faculty, administrators, and trustees as to the state of shared governance. A good survey assesses how various constituencies define the current state of shared governance and the desired state of shared governance. Doing so facilitates an analysis of how to close any gaps. Good surveys also seek to assess perceptions of three-way transparency and level of trust, as well as the level of faculty engagement in shared governance. A sample survey can be found in Shared Governance in Times of Change, Second Edition.

Often institutions establish a shared governance task force of faculty, administrators, and trustees to develop and evaluate the results. A shared governance task force can also lead discussions of how to improve shared governance. A shared governance task force should not be a permanent committee so as not to tread on the responsibilities and territories of other governance committees. At Augustana College, to keep the work manageable, I charged the committee to develop two to three recommendations that could be implemented within one year and one or two longer-term recommendations.

3. Build social capital between faculty, administrators, and trustees.

Shared governance cannot work effectively if faculty, administrators, and trustees don’t trust each other. Some degree of suspicion is understandable. Faculty are often focused on the now, including achieving the best outcomes for today’s students. Administrators are often focused on the near, including how to develop and implement strategic plans for the next three to five years. And boards should be focused on the far, including how to advance the institution’s mission for a robust future. But the truth is that successful institutions are focused on all three: the now, the near, and the far. And although their outlooks are different, each stakeholder cares passionately for their institution and each wants to improve the institution to best serve students. Institutions that can build trust and respect among faculty, administrators, and trustees develop ways to engage the expertise and vantage points of all constituencies for the best possible decisions for the now, near, and far.

There are many ways to advance social capital within an institution, but most of them involve being deliberate in helping different constituencies get to know and understand each other. Events such as receptions before board meetings, faculty lectures, and social gatherings at athletic or fine arts events are excellent ways for trustees and faculty members to get to know each other. Some institutions will invite significant numbers of faculty members to board retreats, where discussion of certain agenda items (for example, strategic planning; diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives; student mental health issues) may be enhanced by faculty participation.

When interacting with faculty, it is important for boards to understand the proper role of interaction between faculty and board members. Informal interactions should not supplant the formal channel of governance. Faculty members sometimes lobby board members on issues or projects that are of interest to them, but their views may not reflect the views of faculty as a whole or elected faculty members. Formal engagement in decision-making should be with elected faculty leaders.

4. Ensure that diverse voices are heard in the shared governance process.

The marketplace of ideas necessary to support shared governance is not effective if participants in governance are not diverse. At many institutions, most credit hours are taught by part-time or contingency faculty, yet these faculty members often have only a secondary voice in faculty governance. Faculty leadership is often dominated by more senior members of faculty (sometimes hardened by past shared governance failures) without adequate representation from millennial faculty (often with fresh ideas) who are starting to carry much of the teaching load. Faculty members from historically underrepresented groups are often assigned to so many committees and carry such a heavy informal advising role for historically underrepresented students that there is no time to participate at the higher levels in shared governance. Likewise, by tradition, at many institutions the voices of staff members and junior administrators don’t carry adequate weight. Excluding these groups from meaningful participation in shared governance robs shared governance of the rich texture of differing viewpoints because each of these groups has a different vantage point from which to observe the institution’s effectiveness.

The board should urge that participants in shared governance represent diverse viewpoints. Boards can’t be effective in doing so if trustees are not diverse themselves.

The board should discuss whether they are receiving needed input from part-time and contingency faculty, as well as millennial faculty who are less likely as a generation to participate in what they consider to be endless committee meetings embedded in traditional shared governance. The board should also ask whether there is sufficient student input to consider the views of students and the impact of policies on students.

5. Support programs to strengthen faculty self-governance.

Shared governance of any institution cannot be effective without effective faculty governance of how the faculty operates as a body and the academic program is governed. If faculty systems of self-governance are not sufficient, then no person or group can speak on behalf of the faculty. That makes it nearly impossible for the administration and the board to engage the faculty in shared governance.

One of the most difficult positions in higher education is that of a faculty leader. Many find that when they move to faculty leadership positions, they move from being one of the most popular members of the faculty to one of the least popular. Faculty leaders need support by their administration and board.

Faculty leaders who have a better understanding of the institution as a whole are more likely to help their colleagues move on from constituency-based thinking. Faculty leadership can be strengthened by institutions creating faculty leadership programs, giving current and prospective faculty leaders “a peek under the hood” about how the institution operates and makes decisions. Most institutions send faculty leaders to national faculty leadership training, where faculty members learn from each other. It is important that board leaders publicly recognize the efforts of faculty leadership and encourage administrations to reward faculty leadership (for example, stipends, release time, travel allowance to conferences). Finally, all trustees should be careful not to undermine faculty leadership by “going around” faculty leaders to discuss concerns with their friends or former professors on the faculty.

6. Maintain a commitment to three-way transparency and frequent communication.

The more information faculty have about the institution as a whole, the more likely they are to start thinking institutionally.

At most institutions, information asymmetries can be a challenge to shared governance. Faculty have a deep knowledge of the academic program and the students. Administrators are well versed in budget details and the status of strategic plans. Trustees are usually quite knowledgeable about their fiduciary responsibilities including enterprise risk management and long-term sustainability plans. It’s important to reduce the barriers caused by this information asymmetry by sharing knowledge and educating other constituencies about different areas of expertise.

Transparency includes providing important information early and often and via different methods of transmission. Some read everything that comes across their desks, while others prefer face-to-face

communication or executive summaries of important information. Information shared with faculty must include sufficient background to enable faculty to meaningfully participate in discussion. It must be sufficiently clear and straightforward to be digestible by faculty. I recall being asked by faculty when I was in my first administrative position to engage with them more deeply in budgeting issues. I agreed and provided faculty with a thousand-page printout of the general ledger! I cringe to think of that now. The better way would have been to engage the faculty in a discussion of budget priorities and how to best allocate scarce resources within those priorities.

To advance communication with faculty at Augustana College and overcome the assumption that the board was engaged in “drive-by” management, the board chair and I decided to invite faculty, even in number to the number of members of the board, to a board retreat. The retreat was focused on developing a strategic plan. I was nervous about doing this, until the first day when I observed that board members dressed like faculty members and faculty members dressed like board members. I then knew that faculty members and board members respected each other and desired to have deep meaningful discussion. Augustana decided to continue that tradition every other year. Topics discussed were topics that could benefit by shared governance: strategic planning; diversity, equity, and inclusion; rebounding from COVID-19; and student mental health. Often discussion of these topics was kicked off by a panel of a board member, an administrator, and a faculty member, which provided powerful evidence of a commitment at the retreat to value the voices of all.

7. Respect traditional rules of faculty engagement

Trustees tend to view quality as quality of results, while faculty members put more emphasis on the quality and openness of the process. Make sure that faculty handbooks are honored when making decisions. Strive to find a process for decision-making that seeks wide input and participation. For some board members, it can be frustrating to spend a lot of time seeking agreement on processes for decision-making, but it is worth the investment of time to create goodwill and shared understandings early.

It is also important to understand that little moves forward with a faculty without faculty champions. For new programs, for example, faculty champions can be fostered by involving faculty members early in discussion, providing summer stipends to develop program proposals, and providing administrative assistance (for example, budgeting, assessing program demand) for faculty in helping faculty develop proposals.

Faculty are also more inclined to advance new programs and program development when originated by their faculty colleagues. Several institutions have sponsored future initiatives think tanks, where faculty members can brainstorm on their ideas for keeping their institutions strong. Institutions that have done this have found that a plethora of ideas is usually generated attached to strong faculty champions.

I learned another lesson in my first year as a college president. Just as the spring semester was wrapping up, I announced several new programs that I would like to get ready for the next academic year. The pushback was fierce because it was the end of the academic year and faculty were exhausted. I’ve learned that the academic year has a rhythm to be respected if one is to employ faculty time in shared governance more skillfully. New initiatives should be introduced early in the academic year when energy is higher.

8. Adopt a shared governance mind-set.

Effective boards recognize that effective shared governance requires patience and stamina. After observing hundreds of higher education leaders, it’s clear that those with a “shared governance mind-set” are better able to move shared governance to shared responsibility and accountability.

Leaders with a shared governance mind-set have most of these attributes:

- Humility, recognizing that the best leaders are servant leaders.

- Even tempered and optimistic—even tempers can calm roiled waters, and optimism about shared governance is contagious.

- Strong listening skills and flexibility—strong shared governance leaders recognize that there are 101 solutions to most problems, and it is the task of shared governance to find one of the ten solutions that advance the institution in a way that most can support.

- Cherish diversity—fostering expression of diverse viewpoints creates the marketplace of ideas from which the strongest solutions emerge.

- Students of higher education—strong leaders are willing to learn and set aside assumptions of old ways of thinking.

- Patience—passionate people sometimes overstate their cause in clumsy ways and strong leaders ask whether this is an element of truth in their arguments.

- Respectful—respectful leaders understand that differing opinions arise from differing experiences and that reasonable minds can differ.

- Wisdom to stay in their lane—shared governance leaders know what they know and what they don’t know, relying on the expertise of others when they do not have it.

- Cherish institutional mission—shared governance leaders realize it is not about them, rather it is about the institution’s mission.

Those with a shared governance mind-set are, in short, role models for all who participate in shared governance. They are role models for institutional thinking.

9. Make difficult decisions graciously and courageously.

Shared governance does not mean those with responsibility for the decisions should shy away from difficult and unpopular decisions. No one likes to make decisions that disappoint or cause blowback. But leaders are obligated sometimes to make them. In those cases, it’s important to be transparent about the decision, what it means, how it was made, and how it will impact people. It’s also important to thank all who provided input, observe that reasonable minds can differ and acknowledge the disappointment by those negatively affected by the decision.

When delivering news that is considered bad, it is important to remember the words of Maya Angelou: “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.” Gracious decision-makers state their respect for their communities and how diversity of viewpoints, including opposing viewpoints, can make the community strong.

And an Important Final Best Practice in These Challenging Times: Timely Decision-Making

The important final best practice is to create a sense of urgency to make nimble and courageous decisions within shared governance. The most common criticism of shared governance is that it slows down effective decision-making. The classic reply is that it may slow down decision-making, but it speeds up implementation because shared governance yields greater buy-in. This reply is no longer sufficient. Both decision-making and implementation need to be timely.

For timely decision-making to occur, leaders must be clear about the parameters of the decision-making process. It’s important to communicate the reasons for nimble and timely decision making. Transparency about finances and competitive threats and opportunities aid in this process. All-campus retreats can be an effective way to communicate why decisions need to be made within an identified time frame.

It is helpful, in making timely decisions, to ensure that all college leaders will support the time line. To gain faculty buy-in, before setting time lines, it is helpful to meet with faculty leadership to ensure that they have full information about the need to make decisions. Many presidents explain the reason for tight time lines but show some flexibility to gain faculty leadership support.

It’s also critical for decision-makers to establish (and explain the need for) timetables for making decisions and the process for doing so. It’s helpful to the process for institutions to have a strategic plan that helps set out the timetable for decision-making and implementation.

Those who argue that nimble decision-making is not possible with shared governance, need only look at institutions that powered pandemic responses through systems of shared governance. Faculty demonstrated they are capable of urgent decision-making and rapidly retooling to effectuate those decisions.

When best practices are followed, shared governance can be an important tool for the nimble and courageous decisionmaking needed by colleges and universities. When it works well

and creates shared responsibility and accountability, shared governance is more than a tool of change; it becomes an engine for transformation.

Steven C. Bahls, JD, is president emeritus of Augustana College, where he served as the president for 19 years. He is the author of Shared Governance for Agile Institutions: A Practical Guide for Universities and Colleges in its just-released second edition. He is also a consultant for AGB Consulting.