Opinions expressed in AGB blogs are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions that employ them or of AGB.

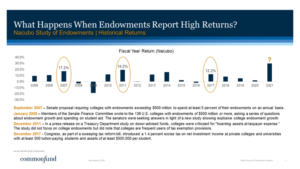

College and university endowments posted record returns in FY 2021. In August, Bloomberg reported a median return before fees of 27 percent for larger endowments. Endowments of $500 million and larger fared even better, with median returns of 34 percent. As a recent article in the Chronicle Review pointed out, these returns come in the wake of widespread budget cuts and layoffs: “While 2021 was a year of staggering endowment growth, 2020 was a year of deep and sometimes existential cuts. At university after university, administrations responded to the pandemic with fiscal discipline and layoffs.” The author goes on to argue that 2021’s “endowment performances represent just another step in the ongoing financialization of higher education, a process that renders university missions subservient to the performance of their investment portfolios” and that “university administrators use the endowment and the constant imperative to reduce spending, reinvest profits, and deliver ever-more-impressive returns as a screen against any check on their managerial powers.”

This should serve as a red flag to college, university, and institutionally related foundation boards; not a warning that presidents, CFOs, and investment managers are transforming institutions into investment companies intent on maximizing returns at the expense of students, faculty, and mission, but that they should be working to educate institutional stakeholders as well as public policymakers about the way endowments work and their role in institutional business models.

The argument that institutions used the crisis as an opportunity to cut expenditures and privileged portfolio growth over the well-being of students, faculty, and staff fails to address the reality of the crisis and the real possibility that, had markets not made a historic recovery, endowments could have sustained losses that would have left scholarships, faculty chairs, and other endowed purposes unfunded or underfunded for years. The argument also disregards some fundamentals of fiduciary responsibility. Think back to 2020: at the point at which institution leaders were cutting budgets they were dealing with sudden drops in enrollment, significant losses in revenue from international students, housing, and athletics, and incurring unbudgeted costs stemming from the pandemic. The first quarter of 2020 also saw one of the most dramatic stock market crashes in history, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average plunging 26 percent in just four days in March. Contrary to the expectations of many, markets quickly recovered and grew to historic highs by the end of the calendar year. Siphoning funds from the endowment in mid-2020 would, however, have meant selling at the bottom of the market and forgoing the gains of the latter half of the year. More critically, it would have exposed endowments to long-term losses in the event that markets had not made such a remarkable recovery and undermined the institution’s ability to sustain funding for financial aid, programs and faculty as endowments recovered. The decision to make financial retrenchments rather than draw down endowments was fully in keeping with the fiduciary obligation to sustain the long-term purchasing power of endowments and intergenerational equity. And, of course, given that the vast majority of endowment funds are restricted by donors for specific purposes, administrations would have violated donor intent, another fiduciary breach, by using endowment funds for any but their designated purposes.

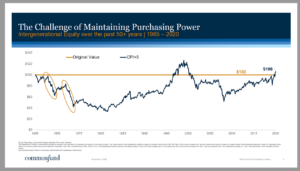

Tim Yates, the president and CEO of Commonfund Asset Management, delivered a presentation to AGB’s Council of Foundation Leaders at their November meeting. Commonfund tracked the purchasing power of a hypothetical portfolio from 1965 to 2020 to illustrate the profound difficulty of maintaining long-term purchasing power of a fund at an annual spending rate of 5 percent.

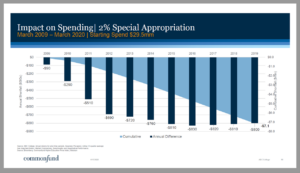

In addition to that analysis, Commonfund looked at the impact that a 2 percent special appropriation taken in 2009 would have had on annual and cumulative spending over the subsequent decade. The chart below is based on a hypothetical $550 million endowment from which an additional 2 percent draw is taken in addition to the annual 5 percent spending draw.

As the Commonfund data suggest, decisions to tap the endowment at moments of crisis or when returns are strongest can handicap spending years into the future, degrading purchasing power that, even absent special appropriations, has proven hard to maintain over the past 50 years and will prove even more challenging if inflation begins to rise in earnest and returns flatten. Yates also pointed out the coincidence of congressional scrutiny of endowment “hoarding” and calls for increased spending or excise taxes on investment income and periods of stellar endowment returns.

In AGB’s updated and expanded Endowment Management for Higher Education (forthcoming January 2022), author Nicole Kraus, the chief client officer of Strategic Investment Group, argues that one of the lessons of recent years is that “(c)ommunication about the investment program among senior officials—including the chair of the board, the chair of the investment committee, the head of institutional development, and the president—must be frequent and clear…The early involvement of all key leaders in certain strategic decisions regarding asset allocation, spending policy, and risk tolerance can be crucial. If any of these officials lose faith in the investment program at the wrong time, they may instigate changes that can wreak havoc on investment returns.” This insight is particularly critical for institutionally related foundations, where the institution president, board members, and CFO may not be directly involved in the management of the endowment. It may be appropriate for some institutions to seize the opportunity of highly appreciated funds and take special appropriations, but before doing so investment committees should undertake a careful analysis of the implications of additional distributions on the future purchasing power of the fund given various market scenarios.

The remarkable growth in endowments in FY 2021 is great news for colleges and universities but will likely trigger questions about why an institution isn’t cashing in on gains and spending more after making such deep cuts to budgets and programs. Institution and foundation leaders should be proactive in educating both internal stakeholders and external constituents about the realities of endowments including:

- That endowed funds are, by and large, restricted by donors for specific purposes and can’t be tapped to cover general operating expenses.

- That endowments have been contributed by donors to provide perpetual benefits to the institution, not short-term budgetary supplements.

- That boards have a fiduciary responsibility to calibrate endowment spending with an eye towards sustaining the long-term purchasing power of the endowment.

- That excess spending and special appropriations can have a significant impact on future spending capacity.

David Bass is AGB’s executive director philanthropic governance.

With thanks to AGB Sustaining Partner Commonfund for their support of this council.