The cost of higher education continues to be a heated topic of discourse for many Americans. While those working in the business of higher education typically understand the factors behind tuition and fees, trustees can play a role in breaking down these complexities for policymakers, the public, and other stakeholders who may not have all the information.

Trustees should consider how their institutions are fulfilling the promise of higher education, and share that with thought leaders, policymakers, and the public.

Students and families are concerned about the cost of college, but what many may not know is that despite rising published costs, institutions are increasing the funds available for financial assistance as well. According to NACUBO, in the 2017-18 academic year, the average student paid 50.5 percent less than the published price.

So how do institutions make up the difference? Tuition makes up only a fraction of revenues at colleges and universities – students pay less in tuition than it costs to educate them. Institutions rely on state appropriations, federal research grants and contracts, patent and trademark royalties, gifts and donations, interest income on the endowment, auxiliary services, state and federal financial assistance programs, investments, and other sources to complement tuition revenue.

A persistent point of confusion for American students and their families is the difference between published tuition and what a student pays after need-based and merit aid are applied. While sticker price has increased substantially over the last 20 years, net price has increased far more slowly.

This misunderstanding around what college can actually cost is a major impediment to many who would apply and enroll, especially first-generation and low-income students.

College endowments allow institutions to support their students, faculty, and other constituents. These funds are heavily monitored and often carry legal restrictions that require spending on specific uses, including scholarships, capital spending, research, and faculty salaries. Still, the 2018 NACUBO-TIAA Study of Endowments® indicated that surveyed institutions used roughly 49 percent of their endowment withdrawals on student scholarships and financial aid programs.

College, university, and foundation boards are responsible for setting endowment spending policies that support current priorities while ensuring there are funds left for future generations.

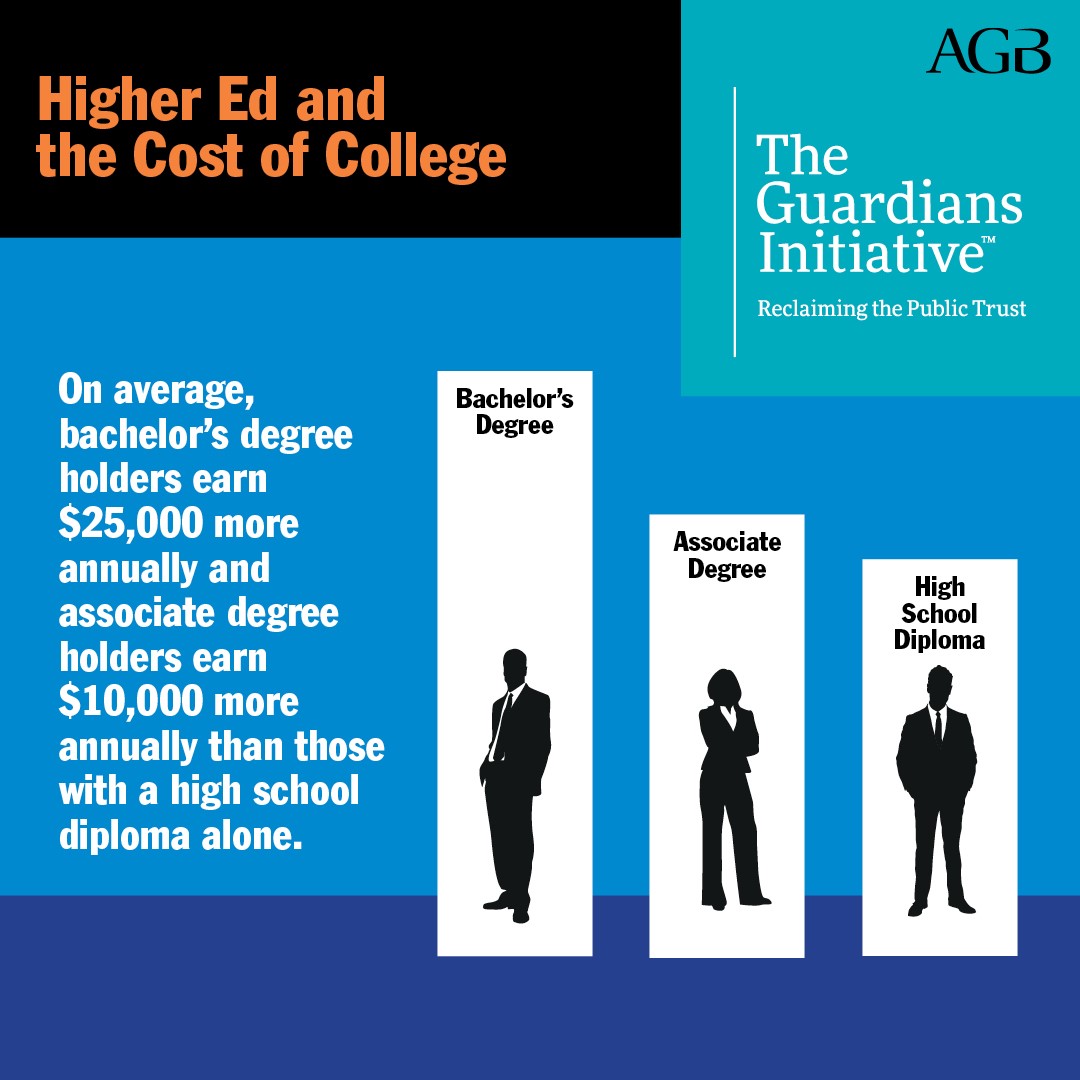

Heavy attention is paid to student debt, and whether students can obtain jobs that allow them to repay that debt. Half of students with associate degrees and one-third of students with bachelor’s degrees graduate with no debt, according to the American Council on Education. The vast majority of borrowers graduate with less than $30,000 debt. More can be found at the College Board website.

There is a direct correlation between earning potential and having a college degree. Additionally, unemployment for those with a college degree is far lower than for those with only a high school diploma during hard economic times.

Higher education leaders share the public’s concern about the cost of college. In fact, according to AGB’s 2018 Trustee Index, board members say that the price of college for students and families is their biggest concern for the future of higher education. Colleges and universities and are taking steps to seek savings through administrative restructuring, shared contracts and services, energy efficiency, and debt financing, among other approaches.