- Public opinion regarding higher education has grown more negative in the years since 2015. That downturn has been matched by a drop in undergraduate enrollment.

- Students and prospective students identify financial pressures as the greatest obstacle to attending and completing college.

- On average, the value of a college degree remains high, but new research shows that the payoff of a college degree is less reliable than in earlier years. As a result, attending college has become a riskier undertaking, especially for lower-income students.

- Students who leave college with debt and no degree may be worse off than peers with no college at all. Boards should monitor data on retention, completion, and debt burden, and understand and address barriers to completion.

- Colleges can do more to address students’ financial concerns, including offering more transparency in financial aid offers to students they admit.

- Students benefit from work-based learning, especially paid internships, but those opportunities are not evenly distributed among the student population.

When the presidents of three of the nation’s most selective private colleges were called to testify before a U.S. House committee in December 2023, there was no indication in advance that the session would turn out to be such a consequential moment in the recent history of American higher education. In response to questions about campus antisemitism from Rep. Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), the three presidents—Claudine Gay from Harvard University, Sally Kornbluth from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Liz Magill from the University of Pennsylvania—offered halting, legalistic responses. Weeks of controversy followed, along with an outpouring of criticism aimed not only at the three presidents but at higher education in general, criticism that quickly moved far beyond the narrow question of who was allowed to say what on these elite campuses. Both Magill and Gay stepped down, and many in higher education—including administrators, faculty, and trustees—felt caught off guard by how quickly the conflagration had ignited and by how few defenders American colleges and universities seemed to have in their corner once the fire began to spread.

In retrospect, though, perhaps we shouldn’t have been so surprised.

Throughout the twentieth century and well into the twenty-first, higher education was one of the nation’s most respected institutions. For much of that era, only a minority of young people attended college, but most Americans—even those who never set foot on a university campus—saw higher education as an important positive force in civic life.

In recent years, though, those positive feelings have been eroding. A little less than a decade ago, public opinion polls began to show signs that Americans were turning against college as an institution. In a 2015 Pew survey, two-thirds of Americans said that higher education was having a positive impact on the country; by 2019, that portion had fallen to half. In 2015, Gallup reported that 57 percent of Americans said they had at least “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education; last summer, only 38 percent of Americans said the same.

As public opinion soured, undergraduate enrollment fell. In 2016, 70 percent of high school graduates were going straight to college; today, just 62 percent of new high school graduates are doing so. The total undergraduate population in the United States has shrunk significantly in recent years, from 18 million students in 2010 to 15.5 million in 2021.

Back in the Obama years, an ambitious, even idealistic attitude pervaded much of higher education. Major projects launched by the White House, by nonprofits, and by foundations sought to dramatically increase the number of Americans who were graduating from college. Today, many of those initiatives have stalled or failed outright. In 2009, President Obama pledged that by 2020, the United States would once again lead the world in the share of its young people graduating from college. In fact, we remain stuck around twelfth place internationally. In 2008, the Lumina Foundation set a goal to increase the share of young people with a college credential by more than 20 percentage points by 2025. With that deadline only months away, we are less than halfway to that goal.

Other initiatives that began during that optimistic moment aimed not just at trying to boost college graduation numbers overall but at improving equity in higher education as well. Beginning in 2016, more than a hundred selective colleges banded together in a well-funded project called the American Talent Initiative that pledged to vastly increase the number of low-income students attending and graduating from the country’s most prestigious universities. The goal was to boost the number of such students enrolled at high-graduation-rate institutions by 50,000 before 2025. Instead, since 2017, the data have been moving in the wrong direction: elite colleges have been admitting fewer low-income students each successive year. As a result, American higher education is now more divided than ever by students’ family income: our nation’s most well-funded universities have come to seem more and more like exclusive clubs for the children of high-income families, while working-class and low-income students are increasingly relegated to colleges that have fewer resources and lower graduation rates.

When you ask young Americans what is holding them back from succeeding in higher education, their answers usually have to do with money. In 2022, the Gates Foundation underwrote a series of focus groups and national surveys of high school graduates who had not yet chosen to enroll in college. When students were asked for the number one reason they hadn’t pursued a degree, they said it was because college was too expensive.1 If they were able to go to college, they were asked, what would be their chief goal? To be able to make more money. And what intervention would be most valuable in helping them complete a degree? Anything that would allow them to avoid debt.

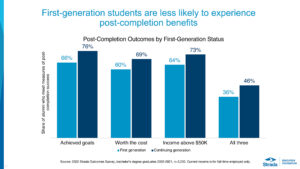

This growing concern about cost and value can be seen not just among those who haven’t enrolled in college—it’s apparent among college grads as well. A 2022 survey by the Strada Education Foundation found that a third of recent college graduates believe that their degree was not worth the cost, with Black graduates and first-generation graduates being more likely than others to say that their investment in college wasn’t worth it.2

Unpacking the Cost-Value Nexus

To many in higher education, these numbers have come as surprising and distressing news. For a long time, a bedrock belief among college educators and administrators has been that a college degree is almost always worth the investment of time and money—and indeed, that a degree pays off even more for those who grow up in disadvantaged circumstances than it does for those who grow up with more privilege.

This institutional faith in the value of a college degree is, in certain important ways, supported by the data. The college wage premium—the term economists use for the financial advantage enjoyed by college graduates—is as high as it ever has been. On average, a typical American college graduate with a B.A. and no further degree earns two-thirds more than a typical high school graduate. By that measure, a college degree still does pay off, in a big way.

But those graduates who told the Strada Foundation’s poll takers that their degree hadn’t paid off were not necessarily miscalculating. Recent research in economics has found that the financial value of a college degree has become much less reliable, and more variable, than it was in the past. A few decades ago, a B.A. offered students a fairly predictable, stable salary boost. Now, some B.A. holders are making a mint, while many others are really struggling.

Douglas Webber, an economist with the Federal Reserve Board, has conducted some of the most significant research on this question, most of it done while he was a professor at Temple University. A college degree still pays off for many students, Webber found, but students’ return on investment (ROI) depends heavily on a variety of factors, from the college major they choose to the tuition they pay to their own demographic profile. “While the expected return to attending college remains high,” Webber wrote in a 2021 paper, “the downside risk (driven largely by student debt and a high degree of noncompletion) is also nontrivial. As in many other contexts, the burden of this risk is not shared equally across the population but is shouldered most acutely by students from low-income backgrounds, particularly among underrepresented minority groups.”3

The greatest financial burden, Webber and a colleague explained in a separate paper published last year, is experienced by the millions of young Americans who enroll in college, go into debt to pay for it, and leave without a degree.4 (About 40 percent of American undergraduates enroll but never finish, and they come disproportionately from lower-income families.) Those non-completers, Webber found, go on to do worse, on average, than high school graduates who never attended college at all. In many cases, their financial situation is quite dire: two-thirds of adults with student debt and no degree told the Federal Reserve’s researchers that it would be difficult for them to cover a $400 expense.

Webber’s data illuminates the cracks that are emerging in the “attainment agenda” that has dominated higher education policy and practice over the last decade. While improving attainment overall remains a crucial national goal, increasing the number of American college graduates alone is no longer sufficient to maintain higher education’s position as an engine of social mobility and economic competitiveness. The next step for the field may be to address the gaps in the system that are allowing so many young people to enroll—and even to graduate—without a clear path toward financial stability and career opportunity.

A college degree in the United States was once a reliable guarantee of a comfortable middle-class life. A generation or two ago, it didn’t matter so much what you studied in college or even how well you performed. If you made it through four years, a good job would likely be waiting for you. As a result, college administrators in that era didn’t worry too much about students’ ROI; indeed, for many administrators and faculty members, ROI was a foreign concept. Somehow, success would just magically happen for students: you go to college, read some books, work some equations, attend some parties, and then graduate into a stable, secure adult life.

For many students today, however, that idyllic arrangement no longer seems within reach. The opportunities available to B.A. holders have grown more precarious and uncertain, while the cost of attending college has sharply increased. Over the last three decades, at four-year colleges, the sticker tuition price—adjusted for inflation—has doubled, and over the last twenty years, the total student debt carried by Americans has more than tripled.

Threat or … Opportunity?

Given the shifts underway in both the economy and in public opinion, institutions of higher education in the United States now face both a threat and an opportunity. The risks for administrators and trustees in the next few years include shrinking enrollment, significant financial challenges, and more intense political and legislative scrutiny and opposition. The opportunity is to face these risks head on—to address the very real problems that are at the root of this growing public discontent.

Students and their families want results from higher education that, for many, higher education is not currently delivering. But that shortfall is not inevitable. There are policies and practices that could significantly shift the relationship that colleges have with their current and prospective students—changes that could improve the public standing of higher education by improving the actual experience of students, families, and community members.

Below are five suggestions on how that shift might begin.

1. Take student concerns about cost more seriously.

There are a number of competing theories for why the cost of college has increased so sharply over the last thirty years. Much of the responsibility certainly lies with state governments, which between 1980 and 2015 cut the amount spent on public higher education relative to personal income nearly in half. As states reduced their support of public colleges and universities, where more than three-quarters of all college students were enrolled, more and more of the financial burden fell to students and their families. Increased borrowing and debt followed.

Those funding cuts created problems for students that went beyond rising tuition. To boost revenue, state flagships often increased their recruitment of out-of-state and international students, making those colleges less accessible to state residents. (The University of Vermont now enrolls more freshmen from Massachusetts than from Vermont.) Meanwhile, at less selective public colleges, including community colleges, per-student spending fell, which often led to significant cuts in the student services and support systems that many undergraduates depended on to help them reach graduation.

During this same era, private universities embraced the principles of enrollment management, a set of innovative practices pioneered in the 1970s by Jack Maguire, then the dean of admissions at Boston College. Maguire was among the first to realize that admissions and aid policies could have an enormous impact on a college’s financial health. By targeting selected students with strategically deployed financial aid, Maguire was able to boost the bottom line at Boston College. In subsequent decades, Maguire’s innovations spread, and along the way they were turbocharged by the boom in information technology. Now, after waves of expansion and consolidation, a handful of giant corporations dominate the field of enrollment management, all of them deploying advanced data analytics and sophisticated prediction software to help colleges precisely identify, admit, and enroll the students they desire most.

But those innovations have come at a cost—one that both colleges and students are now paying. Enrollment management benefited early-adopter colleges when just a few of them were using Maguire’s techniques to vanquish the competition. Now that nearly every college uses the same tools, enrollment management has become, for many colleges, a self-defeating trap. The algorithms at the heart of the business inevitably push colleges to admit a greater number of affluent students and fewer working-class students—while compelling colleges to offer those rich kids greater discounts, in the form of “merit aid,” to entice them to attend. That leaves colleges less able to offer genuine need-based aid, which means that middle-class and working-class students, when they are admitted, are often saddled with unmanageable tuition expenses and towering debt.

According to the basic logic of budgeting, colleges could improve their financial health by reducing their expenses. Yet the logic of enrollment management dictates that colleges continually spend more, especially on the student amenities that affluent applicants seem to desire. The Wall Street Journal calculated last year that the price of even the lower-cost dorm rooms on American college campuses has gone up an average of 70 percent, adjusted for inflation, over the last 20 years, while the price for the more luxurious dorm rooms has increased even faster.5

Spa-like gyms and hotel-style dorms may appeal to the wealthy students that colleges are competing for. But non-affluent students and their families are not looking for luxury; they are looking for value. The colleges that find their way out of the enrollment management trap first—that figure out how to genuinely cut costs, significantly reduce tuition, and deliver a good-quality education for less—will not only win public support but may also discover an untapped pool of applicants who are as tired of the enrollment management game as many admissions officers are.

2. Be more transparent about costs and benefits.

For many high school seniors and their families, the choice of which college to attend—and whether to attend at all—is one of the most consequential financial decisions they will ever face. It is also often one of the most bewildering. The questions at the heart of this choice are as urgent as the answers are elusive: How much is this really going to cost? And how much will it benefit me in the end? For prospective students and their parents, the difficulty of calculating costs, affordability, and expected benefits further erodes their trust in higher education.

One straightforward reform that would help applicants and their families would be to make financial aid award letters clearer and more transparent. A 2018 analysis of award letters from more than 900 colleges by New America found that many of the aid offers were vague, unclear, or misleading.6 More than a third of the letters didn’t include any information on the actual price students would pay, making it impossible for applicants to understand the aid they were being offered. A 2022 study by the federal Government Accountability Office found that more than 90 percent of award offers either did not provide an estimate of the net price admitted students would pay or understated the price by excluding important expenses.7 Most colleges have also been found to “front load” their financial aid, offering significantly more grant aid to first-year students and then reducing those awards in future years.8 Because of this pattern, high school seniors are often unable to get a realistic sense of their full four-year expense burden, and as a result, they sometimes commit to colleges they can’t afford.

Eliminating front-loading and fixing award letters would be relatively simple reforms. The more complex—though arguably more necessary—change would be to give students more clarity not only on the costs of college, but also on the future benefits. A variety of new initiatives are underway to provide prospective students with a clearer and more realistic sense of how enrolling in different colleges and pursuing different degree paths might realistically pay off for them after graduation. At the think tank Third Way, Michael Itzkowitz developed a metric called the price-to-earnings premium that indicates how long it will take a typical student in a given degree program to recoup the expense of that education.9 Separately, a new group called the Postsecondary Commission is proposing reforms that would require institutions to offer prospective students detailed information on the economic outcomes experienced by their graduates.

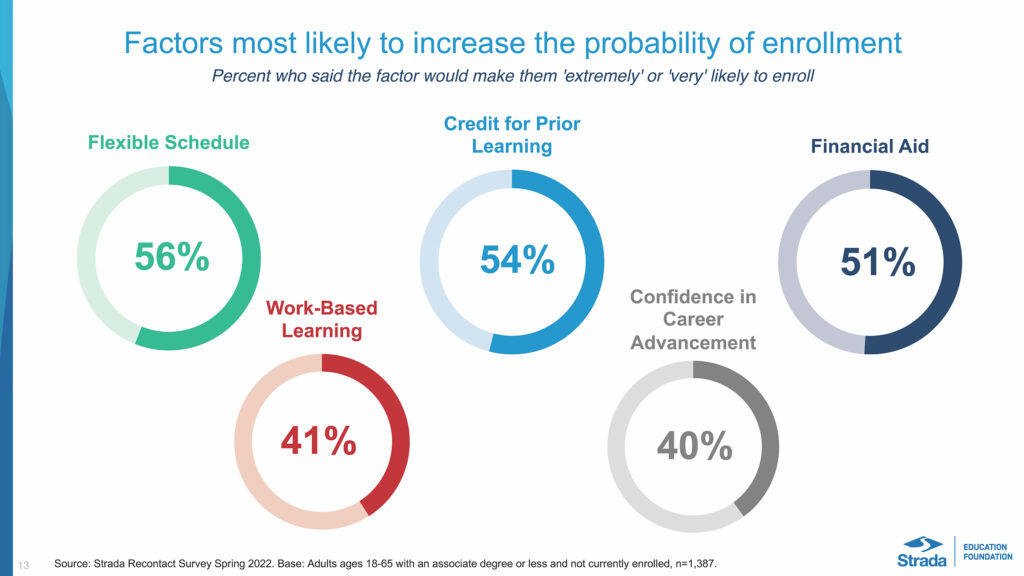

3. Offer students more flexibility.

In a 2022 survey conducted by the Strada Education Foundation, adults without a B.A. degree identified one factor that would be most likely to incline them to enroll in college: a flexible schedule.10 In an earlier era, most students who went to college started right after high school, attended full-time for four consecutive years, and graduated into the workforce. Today, however, many students and prospective students have jobs or families or both, and they want more flexibility in how and when they pursue their degree. Too many institutions have been slow to respond to that demand.

In theory, one of the most cost-effective ways for a student to earn a four-year degree is to enroll first at a local community college and then, after completing two years of study, to transfer to a B.A. program at a four-year institution. In reality, however, this pathway rarely works out well for students. According to federal data, only about one in eight students who enroll full-time in community college go on to receive a bachelor’s degree within six years. Among first-generation and low-income students, the figure is about one in twelve.

Part of the problem is the obstacles that many four-year colleges put in the way of students who want to transfer credits they have earned from community college. As Miguel Cardona, the federal education secretary, said last fall, “Our current higher education system stacks the deck against community college students who aspire to earn four-year degrees.”11 A recent study done at the City University of New York found that graduates of the system’s community colleges who transferred to a B.A. program elsewhere lost, on average, the equivalent of a full semester of work because of credits that didn’t transfer.12

The good news is that there are some encouraging new partnerships that aim to make the transition more effective. The ADVANCE program at Northern Virginia Community College provides a clearly articulated path for students to transfer their credits to George Mason University. Students enroll in ADVANCE at the beginning of their time at the community college and receive personalized coaching designed to make sure that the courses they take will transfer most effectively to George Mason.

Students who are already in the workforce often need a different kind of flexibility: the ability to attend school on their own schedule and to make progress at their own pace—sometimes slower than typical students, and sometimes faster. Students at Duet, a Boston-based nonprofit that works in partnership with Southern New Hampshire University to offer students low-cost associate and bachelor’s degrees, enjoy an unusual degree of flexibility. They progress through a project-based curriculum on their own timetable, getting help remotely from university instructors and in person from Duet coaches at a dedicated study space in downtown Boston. The typical Duet student completes an associate degree in 18 months.13

In a separate initiative, a dozen universities, including Georgetown, have formed a new partnership to design a streamlined, three-year bachelor’s program in which students would receive a bachelor’s degree after completing 100 or fewer credit hours. So far, no accreditor has signed on, but a few have signaled that they are open to the idea of this kind of experimentation.14

4. Build better pathways to the jobs students want.

One of the best ways for students to improve their career trajectory after graduation is to engage in some kind of work-related learning during college. Graduates who did so report higher career satisfaction and a greater sense that their education was worth the cost. Employers agree: in a 2023 survey, they said that internship experience was the number one attribute they looked for when choosing between two equally qualified candidates. That extra attention from employers often pays off for job seekers: on average, a paid internship in college leads to a $3,000 salary boost a year out of school.15

But there is an important distinction within this research. Whereas paid internships produce a clear financial benefit for college students, unpaid internships and other work-based learning experiences on average do not. And though more than 80 percent of college students take part in some form of work-based learning, only 29 percent have a paid internship during college. What’s more, those paid internships are not evenly distributed. Thirty-seven percent of white male students have a paid internship in college, compared with just 20 percent of Black male students. Affluent students are 7 percentage points more likely to have paid internships than Pell-eligible students, and students with college-educated parents are 10 percentage points more likely to land a paid internship than first-generation students.

A handful of organizations are trying to address these inequities. Braven, a nonprofit based in Chicago, enrolls hundreds of students each year at seven colleges around the country in a credit-bearing course that teaches precisely the kind of job-seeking and networking skills that students entering college say they want from their time on campus. Students enrolled in the Braven course practice their interviewing skills, improve their resumes, and strategize how to leverage and expand their personal networks—all of which lead to significant improvements in job placement after graduation.16

Other colleges have sought out collaborations with employers to better align their course offerings with the needs of local labor markets. In Tennessee, Blue Cross Blue Shield and East Tennessee State University introduced a program in 2022 called the BlueSky Tennessee Institute to train graduates of high schools in the Chattanooga area to fill in-demand jobs in technology and analytics. The university offers students an accelerated path to a B.S. degree in computing that comes complete with a job offer from Blue Cross Blue Shield. The degree path is intense but efficient, requiring just twenty-seven months to complete.

5. Expand the definition of campus diversity.

Much of the current national political battle over higher education has focused on the question of diversity. The 2023 Supreme Court decision on affirmative action put new constraints on admissions departments and administrators seeking to diversify their student bodies. Yet there is a paradox at the heart of this controversy: over the last several years, as selective colleges and universities made efforts to improve the racial and cultural diversity of their campuses, the student population at many colleges became less diverse in terms of socioeconomics and political ideology.

As mentioned earlier, the number of lower-income students enrolled at high-graduation-rate colleges has fallen since 2017. At the same time, the nation’s political alignment in terms of educational attainment in the United States has changed. Voters with more years of education have been trending toward the left, while non-college voters have shifted right. On many campuses, meanwhile, left-leaning politics have become more dominant than ever. According to one recent survey, twice as many college freshmen now say they are liberal or left-wing as say they are conservative or right-wing.17 Among faculty, the ratio is five to one; that imbalance has grown from a two-to-one ratio in the mid-1990s.18

As a result, if you’re a working-class kid from a small town in rural America whose parents didn’t go to college, campuses today may not feel particularly welcoming. A few years ago, while I was reporting my most recent book, The Inequality Machine, I spent a lot of time in rural communities, from western North Carolina to central Pennsylvania to the Rio Grande Valley, where I spoke with high school seniors, their families, and their college counselors. Many high-achieving students told me they wanted to go away to college, but a good-quality college education often seemed to them and their parents like an unattainable goal. All around them, they could see examples of young people who went off to college only to return without graduating, discouraged and in debt. Many of the high school seniors I spoke with decided that college just wasn’t worth the emotional effort or the expense.

In the years since, the personal disenfranchisement I have heard among students and their families has hardened, in some communities, into political anger directed at higher education. (Public support for colleges and universities has declined much more sharply since 2015 among Republicans than among Democrats.) This skepticism toward higher education is a problem for those communities, where jobs and other opportunities for young people are often scarce. But it also seems like a problem for higher education. That growing sense of alienation is directly feeding the political headwinds that many college leaders now face.

Colleges today know better than ever how to recruit and admit the students they want, and there are plenty of ways to increase the number and diversity of low-income students on a college campus. A 2023 paper by a group of economists led by Raj Chetty at Harvard identified common private-college admissions practices that benefit high-income students, including favoring the children of alumni and giving admission advantages to athletes in sports that are dominated by private-school students.19 Early admission also has been shown to give a leg up to wealthy applicants, who can commit to a college without needing to compare financial aid offers. Ending those three practices would go a long way toward increasing socioeconomic diversity on campus. But this is unlikely to happen without a genuine commitment by leaders in higher education, including trustees, to the idea that making their campuses more broadly diverse and welcoming is a true priority.

These five strategies are not the complete answer to higher education’s current moment of crisis. Colleges still face funding shortfalls, a demographic cliff, and labor unrest, among other challenges. But any solution has to start from an awareness that there is a growing disconnect between what young people and their families want from higher education and what the nation’s colleges and universities are delivering. Effectively addressing that disconnect could help restore the sense of esteem and respect that higher education enjoyed in the United States not so long ago.

Paul Tough is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and the author of four books including, most recently, The Inequality Machine: How College Divides Us.

Endnotes

2. Strada Education Network, “Value Beyond the Degree: Alumni Perspectives on How College Experiences Improve Their Lives” (November 16, 2022).

3. Douglas A. Webber, “A Growing Divide: The Promise and Pitfalls of Higher Education for the Working Class,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (August 23, 2021).

4. Jacob Lockwood and Douglas Webber, “Non-Completion, Student Debt, and Financial Well-Being: Evidence from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking,” FEDS Notes (August 21, 2023).

5. Melissa Korn and Shane Shifflett, “Swimming Pools and Granite Countertops: How College Dorms Got So Expensive,” Wall Street Journal (December 20, 2023).

6. Stephen Burd, Rachel Fishman, Laura Keane, and Julie Habbert, “Decoding the Cost of College: The Case for Transparent Financial Aid Award Letters,” New America and uAspire (June 2018).

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Financial Aid Offers: Action Needed to Improve Information on College Costs and Student Aid” (December 5, 2022).

9. Michael Itzkowitz, “Price-to-Earnings Premium: A New Way of Measuring Return on Investment in Higher Ed,” Third Way (April 1, 2020).

10. Strada Education Network, “Education Expectations: Views on the Value of College and Likelihood to Enroll” (June 15, 2022).

11. Carolyn Thompson, “Few Community College Students Go On to Earn 4-Year Degrees. Some States Have Found Ways to Help,” Associated Press (November 9, 2023).

12. Collin Binkley, “‘Waste of Time’: Community College Transfers Derail Students,” Associated Press (May 2, 2023), https://apnews.com/article/bachelor-degree-community-college-transfer-credits-cec0154f260c130fbbfcb593de77e4da.

13. John Gabrieli, Martin West, and Katherine Larned et al., “College Re-Imagined: Can a New Model Help Close Higher Education’s Equity Gap?” working paper, Harvard Kennedy School (October 2021).

15. Nichole Torpey-Saboe, Elaine Leigh, and Dave Clayton, “The Power of Work-Based Learning,” Strada Education Network (2022).

16. “Empowering the Next Generation of Leaders,” Braven, n.d., https://braven.org/.

17. Ellen Bara Stolzenberg, Melissa Aragon, Edgar Romo, Victoria Couch, Destiny McLennan, Kevin Eagan, and Nathaniel Kang, “The American Freshman: National Norms Fall 2019,” Higher Education Research Institute (2020).

18. Ellen Bara Stolzenberg, Kevin Eagan, Hilary Zimmerman, Jennifer Berdan Lozano, Natacha Cesar-Davis, Melissa Aragon, and Cecilia Rios-Aguilar, “Undergraduate Teaching Faculty: The HERI Faculty Survey 2016–17,” Higher Education Research Institute (2019); Linda J. Sax, Alexander Astin, Marisol Arredondo, and William Korn, “The American College Teacher: National Norms for the 1995–96 HERI Faculty Survey” (September 1996).

RELATED RESOURCES

Trusteeship Magazine Article

The New “R” in Enrollment Management

Reports and Statements

The Promise of Higher Education