In today’s fiercely competitive higher education environment, in an industry plagued by questions around cost relative to value, perceived as having antiquated management and governance models, and facing complex, socially and politically charged issues roiling campuses daily; an institution’s reputation has never been more important, nor more at risk. In this new world, we no longer have the luxury of treating institutional reputation as nebulous and essentially unmanageable. Instead, we each have a fiduciary responsibility to recognize that our reputation is our institution’s most valuable—and fragile—intangible asset.

Core to this shift in perception is understanding how to actively incorporate the concept of reputation into decision-making, particularly at times of significant strategic change or exacerbated risk. Understandably, however, given the nature of reputation this can be challenging. Strategic decision-making tends to rely on key variables that are defined and measurable. Financial risk can be expressed in spreadsheets, charts, and graphs. Proformas with various assumptions about enrollment, operating costs, and other factors provide comfort and a level of predictability. Legal risk is rooted in the discipline and specificity of the law, defining the parameters within which decisions can be made.

But what of reputation and its corollary, reputational risk? The measures available to help understand reputational value and hence risk are imperfect at best. In the corporate world, we can look to stock price, which, arguably, incorporates such key variables as reputation and confidence in leadership. In higher education, we have campus climate surveys and rankings—helpful although arguably themselves at risk. But even with more immediate feedback—think Elon Musk and the impact the Twitter story has on Tesla’s share price—all of these measures are lagging indicators, judgment after the decisions have been made. In short, neither the corporate world nor higher ed has the clear metrics necessary to help guide decision-making relative to reputational risk. Yet the approaches to thinking about reputational risk could not be more different.

In the corporate world, whole teams are devoted to not just building, but also protecting reputation. In higher education, where deep and enduring bonds characterize our relationships with stakeholders and reputation defines who we are, the caretaking of this most important asset is mostly left to chance. At many schools, reputation is simply a convenient shorthand for all that is positive about an institution—its quality of faculty, alumni networks, and research. Management of it is perceived as unseemly. “Shouldn’t reputation just be the organic outcome of reality?” the thinking goes.

But there’s a flaw in this reasoning. All of those good things didn’t just happen by chance. They are the outcome of decades (and sometimes centuries) of strategic decision-making designed to build the institution’s reputation. So, in an industry where reputation is so fundamental and intrinsically more important than it is in the corporate world, shouldn’t we be doing everything in our power to consciously and intentionally protect it?

Outside-In Decision-Making

Reputational risk is created when there is a significant disconnect between an organization’s decisions and the expectations of its stakeholders. Reducing reputational risk, therefore, requires an understanding of the perspective, the expectations, and the information needs of the range of stakeholders who are critical to the institution’s long- term success. What do stakeholders expect of us? How should our decisions align with our core values as an institution? And importantly, how do we reconcile differences in the perception of these values? To do this effectively, we must rely on an “outside-in” approach to decision-making, a methodical evaluation and consideration of impacts and consequences of each decision on key stakeholders—faculty, on staff, on students, on prospective students and families, on donors, and on alumni. Incorporating reputational risk during a time of crisis or significant change is vital and requires:

■ Exploring Dissonant Points of View—Research suggests that “stress makes decision-makers cognitively rigid. They seek premature closure, fail to search all alternatives and … may view subordinates who advocate a different course of action as interference rather than a source of useful information and ideas to improve the decision.”[1] Jan Suwinski, our MBA professor at Cornell, used to jokingly refer to the cultivation of dissonant points of view as “listening to the crazies,” an important way to reveal options typically ignored or discounted.

■ Reducing Overoptimism—At critical junctures, leaders must be able to move beyond what is known to look out and explore the potential impacts and consequences of the situation and subsequent decisions on key stakeholder groups. We can do this by employing a “Planning Case” to constructively engage decision-makers to think beyond current assumptions (which are almost always too optimistic), to stresstest them using a “worst probable case” scenario. This helps us identify and mitigate risks, thereby improving decision-making.

■ Developing Metrics—While metrics are notoriously elusive relative to reputation, we can borrow and adapt to suit our needs. For example, based upon an agreed Planning Case, we can improvise with an Impaired Asset Model. Typically used to write down the value of an asset on an organization’s books that has lost value, we can use it to analyze the potential reputational damage of a specific issue. As with any predictive model, certain assumptions must be made about the nature of the issue, its duration, and impact on revenue (enrollment, donor support, research support, etc.) and expenses (litigation, marketing, etc.) but it adds rigor where previously there was none.

■ Taking a Stakeholder-Centric Approach to Decision-Making and Communications—Especially during a crisis, institutions typically over emphasize the importance of managing the media over the information needs of other critical stakeholders. In fact, it is not unusual to hear faculty, staff, and even board members complain that they learn more about the administration’s response from the local newspaper than they do from the institution’s leadership. In contrast, a “stakeholder-centric” approach reduces criticism and cultivates community support by identifying the issues and information needs of key stakeholders; focusing directly on and making decisions that reflect those needs;

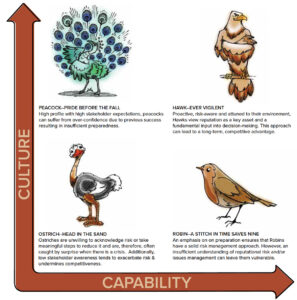

While this matrix is intended to be a lighthearted way of considering differences among institutional cultures and capabilities to address the challenge of reputational risk, we acknowledge that assessing the cultural component can be challenging. Indeed, a peacock or an ostrich organization, for example, is unlikely to ever recognize that it needs to become more like a hawk. In fact, it either thinks that it is already a hawk or that the whole concept is not worth its time.

and finally, communicating those decisions directly to the community thereby bypassing the typically more negative filter of the press. This seems self-evident but inexplicably is often not the approach taken.

Inside-Out Decision-Making

The approach outlined above stands in direct contrast to the normal operating mode of most colleges and universities—especially during a crisis. Instead of focusing on outcomes first, these institutions use, as a starting point, perceived internal constraints which typically shape and limit the range of acceptable options. Generally speaking, decisions are based on financial and/or legal considerations and then communicated out to stakeholders in a way that positions, explains, or justifies the decision.

Unfortunately, this approach often leads to dramatically worse outcomes. Think about the institution that overweighted legal risk to the extent that it never took responsibility and/or apologized for egregious cases of sexual assault, creating massive reputational damage and, actually, increasing legal settlement costs to boot. Or the institution that didn’t anticipate the pushback from parents and faculty to meager increases in adjunct’s salaries, leading to both major reputational fall-out and higher costs in final contracts. Inadequate consideration of reputational risk typically leads not just to reputational damage but higher costs as well.

Making Reputation a Leadership Priority

As a board member, how do you know whether or not your institution is able to effectively manage reputational risk? As briefly discussed in “The Role of the Board in Reducing Reputational Risk” (Trusteeship, November/December 2021) the Reputational Risk Maturity Model can help you measure the institution’s—and the leadership team’s capability—to understand how prepared the institution is to both respond to unexpected crisis events and to proactively identify and mitigate potentially corrosive issues.

Beyond capability, however, there is another important variable to consider, “culture.” The success of an outside-in approach to incorporating reputational risk into decision-making lies in the institution’s management culture, typically revealed at its best and worst during times of significant stress. Culture, in this instance, is a shorthand way to describe the degree to which an institution and its leadership understand and value stakeholder expectations and align decision-making to them.

We can visualize the intersection of these two key ideas through—the requisite—2×2 matrix in which Capability is shown on the x axis and Culture on the y axis, thereby creating four theoretical quadrants with the optimal being the top right. In further deference to the best consulting frameworks, we assigned each quadrant a bird and its associated characteristics to help crystallize the concepts.

While this matrix is intended to be a lighthearted way of considering differences among institutional cultures and capabilities to address the challenge of reputational risk, we acknowledge that assessing the cultural component can be challenging. Indeed, a peacock or an ostrich organization, for example, is unlikely to ever recognize in the first place that it needs to become more like a hawk. In fact, it either thinks—respectively–that it is already a hawk or that the whole concept is not worth its time.

Even if there is a recognition of gaps in capability or culture, most institutions find it difficult to change, and finally do so only when forced by a crisis. We saw this to a lesser extent as institutions needed to rapidly adapt to an evolving Covid environment. While difficult, most institutions are proud about how they were able to adapt over a relatively short period of time, and rightfully so. However, it is when a college or university stands alone in the face of a self-inflicted crisis that the scrutiny is the most intense, and the response most likely to go awry, compounding damage to its reputation, standing, and ongoing viability. In those moments, a “change at the top” is frequently the only way to signal to stakeholders that, going forward, things will be different. And that is a scenario we all should aim to avoid.

The Bottom Line

As daily headlines remind us—from the Varsity Blues scandals to more recent union issues and strikes at both publics and privates—institutions frequently create not just long-term damage to their reputation, but also weaken financial sustainability and increase legal risk when they are perceived as having failed to meet the expectations of those with whom they have an intense and lifelong connection.

As you evaluate your team’s capability to respond to crisis, keep in mind that decisions made without building in reputational risk as a key variable and input into decision-making, risk creating significant disconnect between the institution’s actions and the expectations of its key stakeholders—the very definition of reputational risk.

Simon Barker is the managing partner of Blue Moon Consulting Group (BMCG), a crisis management firm that specializes in higher education. He has supported higher education leaders in their response to protests, academic scandal, sexual assault, natural disasters, data breaches, and workplace violence along with a range of social, financial, and ethical issues. Barker’s book, Preventing Crisis at Your University: The Playbook for Protecting Your Institution’s Reputation, is available from Johns Hopkins University Press. Email: simon@bluemoonconsultinggroup.com.

Jen Rettig is a partner and client lead at Blue Moon Consulting Group. She leads the development of BMCG’s crisis readiness assessment methodology and supports clients through the development of crisis management exercises, plans, and leadership sessions. She also directs stakeholder research and creates proactive messaging platforms including promotional videos and issue dark sites. Email: jen@bluemoonconsultinggroup.com.

1. Alexander L. George, “The Impact of Crisis-Induced Stress on Decision Making,” in “The Medical Implications of Nuclear War” (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1986.)