- Higher education systems educate more than 75 percent of all students (and 80 percent of Pell-eligible students) in four-year public higher education, making systems the backbone of American higher education.

- The differences in roles and responsibilities of system boards and their leaders and campus boards and their leaders are sometimes not understood by participants, leading to tensions, role confusion, and unhealthy competition.

- The concept of systemness can help leaders incorporate coordination and collaboration across the system, optimizing the collective contributions of the system to the best interests of the state it serves, the students it educates, and the functioning of the system as a whole.

- For true systemness to flourish, the roles and responsibilities of system heads and campus heads need to be clearly understood and differentiated and the values of collaboration explicitly outlined.

- A focus on collaboration should be paramount when new leaders are hired, beginning with the composition of the search committee, and continuing through the charge to the search panel, the position description and advertisement, and the entire interview process.

Summary:

The future of higher education lies in greater collaboration and coordination. Here we explore the role of governing boards in overseeing higher education systems, the mindsets needed to adopt “systemness” as an operational standard, and how boards can use hiring and other strategies to leverage the collective assets of a system to support students and the state.

Today’s headlines are filled with stories of university mergers, acquisitions, and closures as means to manage the current financial instability confronting higher education. Unfortunately, while the focus of these efforts is often on cost savings and institutional sustainability, the goals of universities to educate students and serve their states often become afterthoughts.

From our experience working with higher education’s multi-campus systems, we would argue that governing boards could have another strategy at their disposal: “systemness.”

In her 2012 State of the University address, former State University of New York (SUNY) Chancellor Nancy L. Zimpher explained the concept this way: “Systemness is the coordination of multiple components that, when working together, create a network of activity that is more powerful than any action of individual parts on their own.” This definition may sound simple but implementing it in higher education is not.

Systemness comes in many shapes and sizes, from shared purchasing agreements to a common general-education framework across campus. More advanced notions of systemness are exemplified through these initiatives:

- SUNY’s Seamless Transfer initiative, which created a common transfer framework for the entire system and improved the completion rates of transfer students;

- The University System of Georgia’s Momentum Year, which supported all campuses in the system in implementing a “suite of strategies designed to help University System of Georgia students in their crucial first year of college” and propel more of them to complete their degrees; and

- The California State University System’s Graduation Initiative, which took a systemwide approach to advancing student success via the use of data- and evidence-based practices. To date it has outdistanced any other system in closing equity gaps.

As the higher education sector begins to peer over the demographic cliff that is quickly approaching, higher education leaders need to figure out new ways of operating and thinking. Over the past decade, systemness has emerged as a modus-operandi for campus leaders and governing boards seeking to accelerate transformation across multiple campuses.

During our time leading the SUNY system and working with the National Association of System Heads (NASH), we have seen the power of multi-campus collaborations to drive cost reduction, generate revenues, and enhance the resiliency of these systems. Although our work has mainly focused on formal multi-campus systems, the lessons could also apply to other networks and consortiums, which are on the rise among private institutions. However, for ease of description, we write primarily from the perspective of the multi-campus systems that exist under a single governing board.

The Board’s Role in Governing Systems

Multi-campus university systems are the backbone of America’s higher education enterprise. Today, higher education systems educate more than 75 percent of all students (and 80 percent of Pell-eligible students) in four-year public higher education. In addition, systems serve hundreds of thousands of community college students. The functions and perspectives of the boards that govern these institutions determine whether the advantages of being a system can be capitalized upon. Yet the distinction between a system governing board and an institutional governing board lacks clear definition. The result can be a situation in which a system board acts as a governing board of individual constituent institutions rather than as a board of the collective enterprise.

In part, the single institutional governing board was the only type of board until nearly the 20th century. Today, even though most students in the United States attend a campus in a system, most boards still govern individual institutions, primarily due to the large number of smaller private institutions. Given that the prominence and importance of system boards have been increasing, we as a sector need to be more explicit about differentiating the roles of the two types of boards. (Such redefinition of roles may also be needed for boards joining forces through private consortia).

We need to look no further than the recent National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I reorganization in which UCLA announced it would move from the Pac-12 to the Big Ten. The public argument was that it would expand the Big Ten to a nationwide league that could garner more money for its broadcast rights and increase the spoils for each league member. However, UCLA is part of the University of California (UC) system. The move would negatively impact its sister school in Berkeley, which would remain a part of the Pac-12 and likely see a reduction in its revenue sharing. The UC system’s Board of Regents quickly put a hold on the decision until members could review the implications for the system.

Ultimately, the regents allowed UCLA to join the Big Ten as long as the campus agreed to several stipulations, including sharing some of the new revenue with UC Berkeley. However, the chairman of the UC Board of Regents made it clear that, “In the end, we’re a system, not an individual campus. We’ve never had a situation where a decision by one campus had this kind of impact on another campus within our system.”1 The point here is that the board had to assess what was in the best interest of the system, not just that of a single institution.

As a counter-example, the Big 10 recently further expanded to include the University of Oregon, leaving behind its fellow institution Oregon State in the crumbling Pac-12. Because each institution in the state has its own board, UO was able to make the decision without any consideration for other institutions in the state. There will be nothing similar to the revenue sharing happening in the UC system. One can only consider what might have been the outcome had the state not eliminated its state system board in 2015 in favor of the current model.

We should note that most of the work we see around systemness focuses on student success, but this recent high-profile example of athletic conference restructuring provides a public example of how the system board can approach its role. System governance is fundamentally different from institutional governance. Whereas an institution’s governing board seeks to make decisions in the institution’s best interest, the system governing board is responsible for optimizing the collective contributions of the system’s institutions to the best interests of the state it serves, the students it educates, and the system overall. This, at times, may mean the system board, much like the UC board, must make decisions based on goals that differ from those of any of its constituent campuses.

Understanding this distinction in roles between the system board and the institutional board is the first step toward governing for systemness.

Understanding the System as Distinct from Its Campuses

The National Association of System Heads counts more than 60 public systems operating across 44 states. They take a variety of shapes and sizes. Maryland and Wisconsin have statewide systems in which (nearly) all public four-year campuses are part of a single system. In comparison, Texas boasts seven different university systems. The State University of New York has 64 campuses, while the University of Illinois System has three. Some comprehensive systems include two-year and four-year campuses, such as the City University of New York. The University of California is a segmented system comprising only research universities. As Dennis Jones, president emeritus of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems, is fond of saying: “If you have seen one system, you have seen one system.”

A distinguishing feature of any university system, however, is that it is an organizational entity distinct from its constituent campuses. Historically, many systems have acted like a loosely networked confederation of institutions, each with its own goals and mission, even at times competing with the system. As such, system boards sometimes become caught up in governing each institution independently of the others, creating unhealthy tension in the system.

Bruce Johnstone, a former SUNY chancellor and higher education scholar, has written: “As multi-campus system governing boards and system administrations act on behalf of state government and as agents of the statewide public interest, tensions between systems and member institutions—generally seeking maximum autonomy—are inevitable.”2

Yet the system board serves as the fiduciary and legal agent of the entire system; the board is the ultimate authority of the whole. Systemness seeks to leverage this tension as a powerful force of change, rather than a reinforcer of the status quo.

We have seen many examples of systems making decisions organized around the system as a whole, not just the component institutions:

- The University of California system has a single website where students apply for admission and financial aid across the entire system (rather than applying to each campus separately).

- The University of Louisiana’s Complete LA initiative is a single web portal where Louisiana citizens who have some college credit and no degree can identify potential academic programs across the state to complete their degrees. The system (not the institution) provides an academic coach who supports the students throughout their entire course of study, regardless of the institution or major.

- The University System of Maryland created the Britt Kirwan Center for Academic Innovation at the system level “to leverage the power of multi-institutional collaboration to increase access, affordability, and achievement of high-quality credentials for Maryland students.”

- The SUNY Academic and Innovative Leadership (SAIL) Institute provides professional development and leadership training across the system and beyond, providing a more economical and robust model for enhancing the skills of staff and faculty across its 64 campuses.

- The University of Illinois System is the backbone for the Illinois Innovation Network, a state-funded network of university-community-industry-based hubs throughout the state to drive innovation, workforce development, and economic growth in all Illinois regions.

Each of these activities is an example of system-level transformation. None of them could have been enacted by a single institution. Rather such projects require that the system’s board and the leaders it hires operate in an environment in which the system, not the campuses, serves as the primary entity. Thus, systemness is first and foremost about working from a mindset focused on optimizing the overall system and leveraging the size and structure of the system to pursue priority goals and advance needed transformations.

So how does a system board actually implement systemness?

Six Board-Level Drivers of Systemness

A key aspect of adopting systemness is changing the view of systems from merely being allocators of resources, regulators of campus activity, and approvers of new academic programs into being visionaries, facilitators of change, and leaders of transformation. As we note in the book Higher Education Systems 3.0, this shift is fundamental for moving the focus of decision-making from the individual institution to the system as a whole. It is also critical for unleashing the untapped potential of systems and system governing boards.3

Our experience and research show that systemness is optimized when system-board-level, system-administration-level, and campus-level drivers operate in sync.

There are six fundamental board-level drivers that system boards can use as they work toward enacting systemness in their work:

- Goals and Expectations. The system board ultimately sets the stage for all policy discussions and decision-making. For example, SUNY’s board sets an expectation that multidirectional transfer would be easier for all students at all campuses. Minnesota State University’s system board adopted a goal of Equity 2030 and is holding campuses accountable for achieving it. Other boards have set more tactical expectations around aggregating student-level data at the system level or using a common learning management system across all campuses. By staying focused on what is best for students overall and how decisions impact state goals, the system board can work to ensure that institutional and campus leaders and their decisions remain focused on system-level goals.

- Structure. Systemness is enabled (or disabled) by the structures that exist within the system. Library collaboration is a common and often overlooked example of systemness. Many systems and states have created initiatives that enable campus libraries to share resources and partner in joint purchasing contracts of materials. These arrangements expand what most individual institutions can do independently, but it takes a centralized structure to enable that work. Rather than have each campus engage on its own, the Vermont State College System recently created a system-level workforce-development position to coordinate resources across the state to support campuses and optimize service to the state. Other structures include coordinated purchasing offices, IT support, and online program development and delivery.

- Finance. The system board should strategically allocate funds to invest in the infrastructure necessary to support systemness initiatives and to reward institutions for engaging in collaborative activities. In addition to dedicated staffing, funding is often needed to support system-level data collection and analysis, infrastructure for supporting online program recruitment and delivery, software for centralized administrative functions, systemwide professional development, and convening people to learn about and enact transformation efforts.

- Policy Support. Policies can inhibit or support systemness. In our experience, many system-level policies have been developed based on the needs and goals of individual institutions rather than students or the state. As a result, these policies sometimes get in the way of collaboration. Boards should undertake policy audits to ensure their policies are working to support and advance cooperation and system-level transformations.

- Data Utilization. Data collection is a powerful tool and can influence how we identify goals to be pursued and measure the extent to which these goals are achieved. When a system board only views data at the campus level, it can reinforce the tendency to explore campus-level issues and solutions. For example, examining transfer-student success at each SUNY four-year campus prevented us from seeing that we were missing a significant population of students transferring to community colleges from four-year campuses. It is frequently noted that what is measured is what is managed. Given this reality, system boards should push to see both system-level and campus-level data to monitor progress toward board goals/expectations.

- Leadership. Enacting systemness requires leaders of the system and the campuses to understand systemness and work collaboratively toward its implementation. Systemness is a skill that can be taught (as we do in the AGB Leadership and Governance in Higher Education Institute), but there needs to be intentionality by the board regarding whom they hire and the expectations set out for those individuals.

Hiring for Systemness

A critical component of any board is the hiring and firing of the chief executive officer. For system boards, this often means hiring the system and campus executives. If those leaders share an understanding of their complementary roles and the power of systemness, the transformative efforts can be powerful. However, the results can be devastating if those in these roles fight over decision-making authority and institutional autonomy.

Many of us have heard Jim Collins, author of Good to Great, argue that leaders of organizations that go from good to great start “by getting the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus, and the right people in the right seats!” The process of getting leadership selection right is an attribute of organizational discipline. “Discipline,” Collins adds, “is a characteristic of greatness.”4

Although the metaphor is powerful and the importance of hiring it conveys is critical, the idea of a bus propelling forward as people rearrange the seats may not be the best way to capture the notion of work in higher education. The reality is that higher education is a loosely coupled system with many layers of semi-autonomous decision-makers functioning between the system or campus board and the offices, classrooms, and laboratories in which the work of the enterprise actually gets done. In this environment, a more appropriate metaphor is ensuring that everyone in the canoe is paddling in sync toward a destination that they agree on and to which they are committed. Developing that alignment throughout the organization is a crucial aspect of systemness.

In his classic book, Complexity and Control, Richard Elmore observes, “The skillful use of delegated control is central to making implementation work in bottom-heavy, loosely controlled systems. When it becomes necessary to rely mainly on hierarchical control, regulation, and compliance to achieve results, the game is essentially lost.”5

To take this argument full circle, the discipline of selecting good leaders and specific leaders who can perform well in the university system context is the actual connection to greatness. Optimizing a complex system to serve students and the state depends on leaders who can motivate those in the canoe to paddle in the same direction and develop structures supporting that collaborative effort. In our current environment, nothing could be more important. But how can that be achieved?

System Versus Campus Leadership: What’s in a Title?

First, some clarification is needed to discuss the roles of the system head and the campus head. Who does what can become confusing because “chancellor” and “president” are often used interchangeably for these roles. Within SUNY, the head of the system is the chancellor, and the head of the campus is the president. In the University of Wisconsin System, the terms are reversed, with president leading the system and chancellors leading each campus. Unfortunately, the usage of these terms is based more on historical idiosyncrasies than an honest description of duties.

While the title may not clearly represent duties, the roles differ considerably. The system head is likely the most comparable to a cross between the head of a government agency and the CEO of a large organization. The CEO is typically the highest-ranking individual in an organization and has responsibility for the comprehensive vision, strategy, and decision-making related to the overall direction of the entity and the use of resources. The board selects the CEO, who serves as the primary link between the board and the organization. In addition, in some cases, the CEO also functions as a quasi-agency head, with some level of engagement with the state’s elected leaders.

The campus head may more closely resemble the president of an organization that is part of a larger conglomerate. The head of each campus provides executive leadership for the institution and is responsible for the execution of strategy; leading the institution’s teaching, research, and service activities in collaboration with the faculty; and ensuring the institution is advancing its mission in a fiscally responsible way. Ideally, the work of the campus head is congruent with the direction set by the system CEO, although this is not always the case. Typically, while the system board may play a role in the final selection of campus heads, the individuals chosen report to the system CEO.

Role confusion is a major obstacle to advancing systemness, sometimes resulting in the system CEO and campus head tangling over roles and responsibilities instead of collaborating toward a shared vision and strategy. More often than not, this situation arises when the system head and the system board do not understand that the role of the system head is to manage the pursuit of a “public agenda”—an agenda based on service to students and the state. It is not to manage, from one step removed, the constituent campuses of the system.

Moving Toward Leadership for Systemness

It is easy to understand why there is role confusion between system and campus executives. Similar confusion often confronts system and campus boards. Boards responsible for a single institution typically hire an individual to be president and CEO.

Even within systems, the institution is the primary connection for nearly all stakeholder groups in higher education. In contrast, systems are often perceived as the foil to a campus’s best interest. The lore of higher education is littered with stories of strong “presidents and CEOs”—such as Charles William Eliot, president of Harvard from 1869 to 1909, or Father Theodore Hesburgh, president of the University of Notre Dame from 1952 to 1987—who transformed their institutions and served as public intellectuals. Seldom are system heads included in this list of transformative leaders; Clark Kerr of the University of California system stands out as a rare exception.

This imagery has also given rise to a perception of systems being a loose confederation of largely independent institutions, instead of a naturally networked organization that can take advantage of the collective resources of the entire system to benefit students and the state. One of the ways to move toward a different orientation is through a systemness strategy, where the system head and campus head work collaboratively in the best interest of the entire organization, not just that of each institution within the system.

Thus, in the case of multi-institution systems, those roles should be considered distinct from each other, with the system head serving as the CEO and the campus head serving in the local presidential role. The lack of clarity of these roles often leads to confusion over authority and responsibility, with both the system head and campus head trying to be CEO and president and fighting over authority. This tension inevitably consumes limited resources and serves as a barrier to meaningful transformation.

In the 2022 book Higher Education Systems Redesigned, Jonathan Gagliardi and Jason Lane explain:

Executing system-level change necessitates understanding the dynamics between systems and campuses. Too often conflict arises when systems and campuses fight over the line where campus autonomy stops and system authority begins. In some cases, this tension is inevitable, such as when systems execute their authority to determine which campuses are able to offer which academic programs, leading to system administration telling some campuses they cannot offer everything they wish. However, when a system leader sees his or her role as the same as the campus [president], the conflict can become all-consuming and debilitating. In such situations, it becomes very difficult to develop healthy and productive relationships between the campus and the system administration. Instead, each blames the other for interfering with progress, argues that their way is the right way, and fails to see where collaboration can advance their collective interests…. [E]ffective system leaders realize that systems, when possible, do not compete with institutions for the same domains of authority. Rather, they pursue activities and functions that are cross-cutting and supportive of campus missions.6

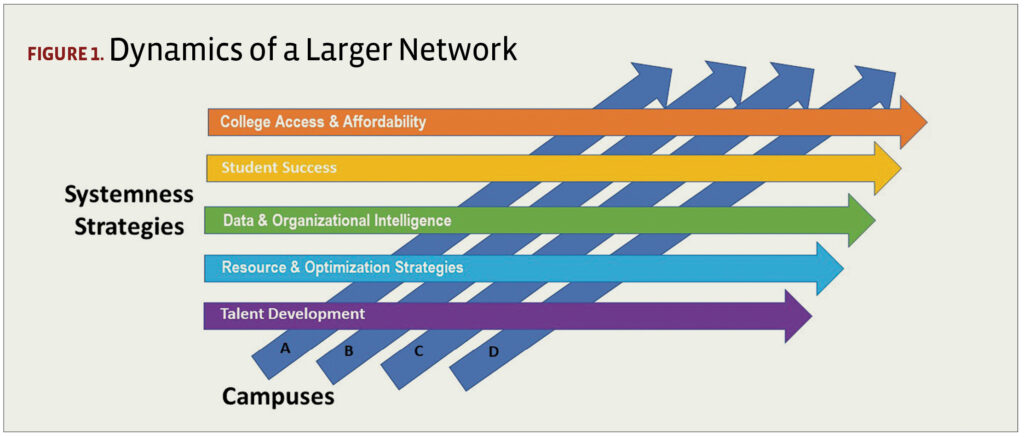

Campus heads at the same time must also understand that they are not part of a federation of loosely coupled institutions, each with its own agenda, mission, and vision. As shown in Figure 1, the system’s real power lies in the complementary dynamics of being part of a larger network. That power can best be harnessed to positively impact students and the state when the leaders work together toward a shared vision.

Why Hiring Matters

Role clarification starts with the hiring process. Given that the lore of higher education in the United States reinforces the concept of a campus head being both president and CEO, most candidates for these roles will default toward that orientation unless the board makes it clear otherwise. Meanwhile, the concept of a system CEO still needs to be defined in both mainstream and scholarly literature.

Time and again, we have seen examples of campus heads within systems who publicly chafe about being part of the system and having to report to a system CEO, even actively working against the system’s strategy if it is deemed to run counter to the vision of the campus head. On the other hand, we have also seen system CEOs, often former campus heads, who see their role as running the individual campuses, even though those entities have a designated executive leader.

In our experience, transformation occurs at its highest level when the system CEO and campus head understand their complementary roles. When this happens, the campus head runs the institution in line with the overall strategy and direction of the system, and the system CEO identifies the agenda of service to students and the state and advances activities that use system assets in pursuit of that agenda. It might even mean undertaking some systemwide reorganization, such as creating consolidated administrative structures that support work across multiple campuses.

That is why hiring matters. If a board is not intentional about the responsibilities of each role, nor clear with the candidates about its expectations, the tensions we’ve described are very likely to occur. Yet if a system board wishes to move toward a more effective leadership structure that can address future challenges, there is a way forward.

Four Steps for Hiring for Systemness

Hiring and onboarding system CEOs and campus heads to their appropriate roles can be complicated. The advice we provide here is relatively straightforward, but implementing it over several years requires changing the organizational culture from being highly competitive to building a team of campus heads eager to collaborate with each other. In turn, their campuses (at least most of them) embrace and actively work to engage in systemness.

The following advice is derived from our experience in consulting with systems leaders and boards and in hiring 54 campus heads for SUNY. Although the following steps are presented as a description of the process employed at SUNY, the process was thoughtfully created, tested in a large number of searches, and revised as necessary. As a result, this set of steps can be considered “good practice,” and we recommend their adoption for use in other systems. In addition, we believe there are lessons from these campus head searches that boards can use to inform searches for system CEOs as well.

Step 1: Composition of the Search Committee. Hiring system CEOs and campus heads to advance systemness starts at the beginning of the search process. The process, including search-committee composition, for a campus head in SUNY was defined in both state statute and board policy for the system. Each system is different in its approach, so we’ll not go into detail except to say that the search committee was heavily populated by constituents of the local campus. At the time, members of the SUNY governing board were not on the search committee, although the system CEO was able to designate a representative to be a voting member of the search committee. The individuals the system CEO identified for those roles became very important because they were instrumental in ensuring the system perspective was an integral part of the search process.

There are examples across the country of system board members serving on search committees, chairing search committees, or otherwise auditing the search process to ensure attention to systemness when candidates for campus heads are recommended for consideration. These highly local models depend on particular traditions or variants across systems. The bottom line is, if the intended outcome is systemness, it is essential that the search committee have members who understand that and can speak to that requirement. We would go so far as recommending that a representative of the board or system CEO be a member of all search committees to ensure that the expectation that the campus leader function as a member of the system is clearly understood.

Step 2: The Charge to the Committee. At the first meeting of the search committee, the system CEO and/or board chair should join the committee (even if by video) to deliver the charge to the committee, which should also be provided in writing. Each charge should follow a very similar format. It typically would include highlighting key characteristics of the campus, outlining foundational expectations of the role from the chancellor and the trustees, and outlining the basic process to be used in the search. Importantly, that document should describe the campus leader as both the head of the campus and a member of the system CEO’s leadership team, and it should note that the successful individual will need to balance those roles and acknowledge that at times there might even be perceived conflict between the two roles.

The charge has two key audiences. The primary audience is the individuals on the search committee charged with advancing a number of candidates to the system CEO for further consideration. The secondary audience, although no less important, is the internal and external stakeholders of the campus. The charge typically should be posted online on the search committee’s web page; often it is the only communique from the system CEO about what the campus might expect in its next campus CEO.

Noting that the campus head also has a role in working with the system CEO reminds the readers of the charge that the campus and its head are part of a larger system. It underlines that there is an important and symbiotic relationship between the system and the campus, which the campus head will have an important role in furthering.

Step 3: The Ad and Position Description. For candidates, the search ad is often a primary source of information. The ad is more than an opportunity to describe the necessary requirements and the description of the job and a way to brag about the institution. It is also the system’s opportunity to set expectations in terms of what the board expects that campus head to do or how the campus head will be expected to act once he or she joins the system.

As we did several searches a year, we developed standard boilerplate language for each ad that described the system and the general context in which the successful candidate would be expected to operate. Part of that language included the following statement: “[We are] committed to expanding on SUNY’s ‘systemness’ to ensure that we move the entire [system] forward as a national leader and major driver of academic excellence and economic revitalization in New York State.”

This language signaled that the heads of campuses needed to buy into a larger vision of advancing the system. Each campus would play a role in increasing academic excellence and contributing to the revitalization of the state. SUNY’s strategic plan at the time, The Power of SUNY, was grounded on the idea that SUNY would be instrumental in supporting the state’s emergence from the Great Recession of 2008.

The ad went on to stipulate: “Chancellor Zimpher increasingly looks to our campus [heads] to work collaboratively with other SUNY colleges, administrators, faculty and staff, and surrounding communities to lower cost, enhance productivity, and elevate the importance of degree completion at each institution.”

This language was critical to reinforce the idea that the campus heads were responsible for both their campuses and the system. Further, the expectation was for the successful candidate to collaborate with other campus heads.

To draw on an example outside of SUNY, the University of Illinois System recently hired a new head of its Chicago campus. The first line of the search ad read, “The University of Illinois System is conducting a national search for an individual to serve as the next permanent chancellor of the University of Illinois Chicago and vice president of the University of Illinois System.” The heads of the three campuses in the system also serve as vice presidents of the system and part of the system leadership team. While this may work better for a system with three campuses than 64, it sets a clear expectation that the campus head must balance the duties of chief campus administrator with a role in advancing the system’s goals.

Step 4: The Interview(s). More than soliciting information, the questions asked during the interview process also send signals about what is valued by the search committee and hiring official and what the candidate could expect about the role if chosen as the successful candidate. During each stage of the interview process (namely, the neutral site interviews, campus visits, and system administration visits), a variation of the following question was asked: “If you are the successful candidate, how would you balance the demands (sometimes competing) of being both the [head] of the campus as well as part of the system’s overall leadership team?”

Again, this question served two purposes. First, it allowed the various decision-makers to hear how an individual would approach the work and the extent to which they had considered the duality in the role. Second, it sent a signal to the candidates that reinforced the system CEO’s commitment to systemness and expectation of balancing the responsibilities to lead the campus with those of being part of the system leadership team.

As the concept of systemness began to extend beyond SUNY, it was not unusual to hear candidates integrate the term into their responses. Some even commented that systemness—or positive collaboration between campuses—drew them to the position.

Once a campus head is hired, effectively managing the transition into the new position is key. The focus will inevitably be on getting the individual to the campus and introducing him or her to the community. At SUNY, within the first few weeks of starting the position, the individual was also always invited to the system administration for a one- or two-day visit.

That visit had two purposes. The more operational aspect of the visit was to inform the campus head of the functions performed by the system administration, such as academic program review and system budgeting. The other purpose, perhaps the more important, was to build relationships between the campus head and the system administration staff. We wanted to build a positive and trusting relationship between the campus head and the system, which had not always been the case.

Conclusion

Implementing systemness is not easy and involves much more than hiring, but it is much more achievable when the right individuals are on the leadership team. It took several years to build the SUNY process, but the outcome was worth it. We built a team of campus heads who valued systemness; they said that they joined SUNY because of it. And because they saw collaboration as something important for their own work, not just a bottom-down edict that they were required to do, we began to see presidents organically working together to develop new partnerships. These partnerships ranged from shared academic programming to joint admissions between community colleges and four-year institutions.

Leading for systemness is a skill, and the processes we’ve described allow the board to set a strategic vision for collaboration and to build a team of leaders able to execute that vision and believe in the value of it.

Jason E. Lane, PhD, is the incoming president of the National Association of System Heads (NASH) and dean of the College of Education, Health, and Society at Miami University in Ohio. His previous roles include vice provost of the State University of New York (SUNY) system, dean of the School of Education at SUNY-Albany, and director of the Systems Center at the Rockefeller Institute. A bestselling author, his books include Higher Education Systems 3.0 and Higher Education Systems Redesigned, which explore the rise of systemness.

Nancy L. Zimpher, PhD, is interim executive director of NASH and chancellor emeritus of SUNY, where she served as the 12th chancellor from 2009 to 2017. Earlier, she was president of the University of Cincinnati, chancellor of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, and executive dean of the Professional Colleges and dean of the College of Education at Ohio State University.

Lane and Zimpher also are codirectors of AGB’s Institute for Leadership and Governance in Higher Education.

Notes

1. Witz, Billy, “U.C.L.A. Is Allowed by California Regents to Join Big Ten,” New York Times, December 14, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/14/sports/ncaafootball/ucla-big-ten.html.

2. Lane, Jason E., and D. Bruce Johnstone. Higher Education Systems 3.0: Harnessing Systemness, Delivering Performance (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2013).

4. Collins, Jim, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t (New York, Harper Business, 2001).

RELATED RESOURCES

Reports and Statements

Consequential Board Governance in Public Higher Education Systems