- It is critical for that institutions examine mission statements to make sure they are current, relevant, and effective in charting a course for the future.

- Universities cannot be everything to everyone. Too many strategic goals can undermine a core strategy.

- Boards may need to realign their internal structure to enable strategic change.

- If innovation is important, it needs a place within the institutional structure and

support from the highest levels. - To retain students, colleges and universities need to align educational programs,

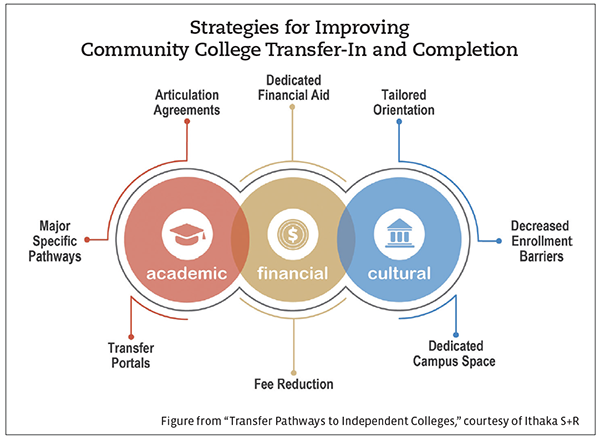

counseling, and student support services. - Improving transfer pathways between two-year and private four-year institutions could enhance the financial health of four-year colleges while raising baccalaureate attainment for community college students.

Twenty years ago, Michael Crow joined Arizona State University (ASU) as a new president committed to creating the “New American University,” as he termed it in his inaugural address. That new pedagogic model would move toward accelerated and continuous innovation, would embrace egalitarian higher education and eschew exclusionary admissions practices, and would match technological advancements in STEM subject research with corresponding liberal arts advances.

That vision has largely been realized, Crow says. ASU has 140,759 students (total) this Fall, up from 55,491 in 2002, including 61,572 online students. In particular, STEM subject graduates have skyrocketed, with engineering graduates increasing from 4,799 in 2002 to 30,000 last year. In fiscal year 2020, the university ranked sixth for research expenditures among institutions without a medical school, according to the National Science Foundation Higher Education Research and Development rankings. The percentage of minority students enrolled has increased from 20.7 percent of all students in fall 2002 to 40.5 percent fall 2021. And ASU has topped the likes of Harvard, Stanford and MIT universities to secure the most innovative university in the country designation eight years running from U.S. News & World Report magazine.

But the quest to build the university of the future should never end, Crow says. Now ASU is integrating virtual reality into learning, with, Crow says, early signs that this will prove a game changer by making difficult STEM subjects learnable for average learners and by opening up higher paying professions that require more technical degrees to a vastly increased pool of college graduates.

“We have found ways to teach and enhance learning for those students,” Crow says. “We just finished last semester with our first virtual reality-based labs with several hundred of our biology students taking labs off the earth in a virtual reality environment built by Steven Spielberg, as designed further by us and a company in Los Angeles called Dreamscape Immersive. It’s a learning tool that is designed to take the biology curriculum and tutor you individually in a manner unique to your learning pathway. And we’ve had kids with low science aptitude coming out with 35 percent improvement in their science aptitude, which we’ve never seen before. We are getting higher science literacy and more people who want to become science majors.”

Crow’s point, however, is not that most higher education institutions should emulate ASU. Rather, it is that many more colleges and universities must innovate and evolve more aggressively to a more diverse and powerful set of value propositions.

“[In American higher education], we have too little diversity, too few institutional methodologies, and too limited a pedagogical design to address the complexities of what lies ahead and to really fully realize the opportunities that we have in front of us,” Crow says. “Each university should strive to be less and less generic, more and more unique, more and more special, and more and more focused on the way that they think they need to do things. And that means having your own unique aspirations.”

This story, the second in a series examining The College of the Future, examines strategic planning, leadership, and programmatic alternatives for colleges and universities. It also examines the related issues of experimentation, innovation and flexibility; alignment, transitions and counseling services; and equity and civil discourse.

The Strategic Imperative

The need for higher education institutions to determine their core value proposition is hardly a new one. Arthur Levine, a professor at New York University and author of a book examining the future of U.S. higher education, The Great Upheaval: Higher Education’s Past, Present, and Uncertain Future, notes that there is a long history of evolutionary developments at inflection points in education that have created more higher education models, as documented in his book.

He says it is critical that institutions examine mission statements to make sure they are current, relevant, and effective in charting a course for the future. Levine notes that university boards should be focused less on degrees and credits—the means of delivery—and more on addressing the core issue of what business they are in.

Western Governors University determined that its North Star was to be responsive to student educational demands, says WGU President Scott Pulsipher. “Our vision is to be the most student-centric university on the planet. Our perception and our belief is that education is a means to an end, and is the primary way—or the single greatest catalyst—for people to change their lives for the better,” Pulsipher says. “That includes things that are not really academic endeavors.”

Joshua Wyner, founder and executive director of the College Excellence Program at the Aspen Institute, says that too many strategic goals undermine a core strategy and that it is instead best to pick two or three key objectives at a time and try to obtain those.

“The vision that presidents have can’t be in 20 parts, which is why many strategic plans don’t lead to substantial change. Plans can’t simply be an aggregation of what different parts of the institution already aim to do and how to make those parts better,” Wyner says. “It has to reflect a vision of the two or three big moves every couple of years that the institution is going to make so that every part of the institution is instituting reforms with a clear and limited set of priorities in mind.”

That involves making choices. Bev Seay, immediate past board chair of the University of Central Florida and board chair of AGB, says universities cannot be everything to everyone. “For universities like UCF, in a large metropolitan area, it’s going to be important that we focus on the areas of our core academic strengths, where we see the future, and specifically, the future of change in our industries. We can’t be dependent on any one industry, because you have different business cycles, and the work we’re doing must apply across multiple industries,” Seay says. “I was very pleased with the strategic plan that we recently crafted as it focused on understanding who we are and who we will be. For example, I’m impressed with the way it identified medical and tourism together as a focus. I think that’s innovative. Also, there is a focus on the space industry, given our proximity and our deep history in that sector. There was discussion of emerging technologies and national security, but the plan focuses on our students, who are my priority.”

In the case of North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University (NCA&T), the largest HBCU in the country and a strong research institution, there was a strategic need to recognize that its nature and competition had changed over time to include non-HBCU peers, says NCA&T Chancellor Harold Martin.

“We had to develop a different peer group where we were competing on those things that matter to parents of well-prepared college students and faculty, who are being recruited by lots of universities,” Martin says. “And so our peers today include only one HBCU but are comparable in Carnegie class and mission. Deciding to do that was a very difficult discussion that we had in the early years of my tenure as chancellor, with our board and with our alumni in particular, because they were afraid that we may be stepping into a space where we lose what has been good to us about being an HBCU, including losing connections with our heritage, shared history, and traditions. And so we’ve had to be very inclusive in those discussions as we have framed our posture for the future.”

NCA&T has been vigorously managing its programmatic offerings to better align them to student needs, he adds. And those programmatic changes resulted in, with the help of consultants, large structural changes, including the disposal of two colleges and the creation of three, Martin says.

Board and Executive Structural Changes

Boards may need to realign their internal structure to enable strategic change, says David Rowe, practice area leader for private higher education and foundations at AGB.

“At most institutions, the traditional governance structure typically extends the stovepipes of the administrative cabinet up into the boardroom,” says Rowe. “As a result, you don’t have any entity that looks across the institution as a whole and thinks strategically, five and ten years out. Increasingly, you’ll see boards that are more aligned toward consistently evaluating and anticipating the evolution of the value proposition; on resource alignment, rather than accumulation of resources, making sure that you’re scaling up and scaling down to meet demand; revenue generation, rather than simply providing the funds for the next good idea that comes along; and increasingly focused on processes that are growth-oriented as opposed to fundamentally selective, exclusionary, and meritocratic.”

Trustee selection is also important. Angel Mendez, a board member at both AGB and Lafayette College, a senior IT executive, and a Lafayette graduate, says it is important that boards of trustees develop a system to cultivate and groom a larger pool of volunteers to help institutional missions and to develop future boards that are effective and diverse.

At Lafayette, in addition to a 35-person board, there are more than 200 volunteer members of non-board committees, Mendez says. “We supervise, if you will, the process of nominating and selecting the leadership and membership of these committees,” Mendez says. “And we observe future leaders and see how strongly they volunteer, advocate, donate and get involved with career services and recruitment of students and so on. And then once a year we bring the chairs of all these councils to the board as well. It is almost a minor league that feeds into our major league, the board. My fear is that at many other institutions people are more reactive than proactive in constructing their boards, or traditionalist in the sense of, ‘I know a guy we can add to the board.’ Because of our committee system, we have probably four or five candidates at least every time a seat opens up whom we can consider. The research is pretty clear, the more diverse the group, the more innovative it is and the less inclined to live on tradition or be enamored with single class solutions or what we’ve always done. Our committee system gives us a chance to have a diverse, qualified slate.”

It also is critical to hire presidents, CEOs and chancellors who are visionary, Wyner says. But often board dynamics impede such hiring, he adds.

“If they want change, boards have got to hire visionary presidents who are willing to take risks,” Wyner says. “When we’ve done research on how community college presidents are hired, we’ve found that boards often do not spend enough time asking what the big goals of the institution are, for the next five to ten years, what the strengths and challenges at the institution are in meeting those goals, and then the attributes they need in a president to capitalize on strengths and overcome the challenges toward achieving those goals. Furthermore, many trustees don’t value risk taking and strategic vision as much as they value relationship building and fiscal conservatism. If you think about those two qualities, a focus that’s about fiscal conservatism and stewardship, and relationship building, are you likely to find a strategist who’s a risk-taker? Even when they hire a strategic risk-taker, presidents sometime fail because the board doesn’t understand that change is hard. Boards need to very intentionally support bold leaders in making the big changes needed and overcoming the temporary setbacks and challenges that any major change will bring.”

Lafayette College’s current president, Nicole Hurd, was previously assistant dean and director of the Center for Undergraduate Excellence at the University of Virginia, where she launched what became College Advising Corps (CAC) as a pilot program in 2005. She led CAC until joining Lafayette in 2021. CAC has helped more than 525,000 low-income, first-generation, and underrepresented students enroll in higher education by placing more than 800 recent college graduates each year as near-peer advisers in 795 high schools across America. She is applying that work to recruiting at Lafayette.

“Talent is everywhere—talent is not bound to zip code and is not just in urban areas or rural areas,” Hurd says. “And I think I’ve been challenging my colleagues here to start getting much more aggressive about how we recruit talent. I think I learned through the work with CAC that we have to be out there, we have to be proactive, we have to explain to families what our cost structure really is because people get very scared of the sticker price, which is not what low income families will actually pay; the value of instruction by faculty who are teachers and scholars; and what it means to have a personalized experience and to be a small liberal arts college that has strengths in the traditional liberal arts and engineering, all of which makes us much more attractive. We have to tell that story.”

One way to instantly diversify and increase the robustness of institutional offerings is through combinations. Combinations between for-profit institutions and traditional higher education institutions are one example of mutually beneficial structural change, Levine says. “Look at Purdue Global’s acquisition of Kaplan in 2018,” Levine says. “They took an open admission, for-profit and they brought it to a public not-for-profit. And what happened was that Purdue, which has been a highly selective institution, gained access to underenrolled students, such as older students and students of color. It also raised academic standards of the for-profit unit. It’s now public and anything they do is publicly viewable. So it established a minimum standard.”

Building Upon Competitive Edges

Many join ASU’s Crow in stressing the importance of schools building upon their comparative advantages and decisive edges. For Cornell College of Mount Vernon, Iowa, one such advantage is its One Course At A Time block system program, a pedagogic structure followed by only a handful of colleges and universities nationwide, under which undergraduate students take only a single class at a time for each three-and-one-half-week increment, says Cornell College President Jonathan Brand.

“We get to do something that basically no other school does, which is our students get to start walking their path multiple times over the course of four years,” Brand says. “And so we have students who after four years might study abroad four different times. We can do that [on the block system] because students don’t have four or five classes they have to juggle, they just have that one class. And if they’re a serious pre-med student or a serious athlete and they have a season on campus that they don’t want to miss, which would prevent them from studying abroad at a semester system school for a semester or a year, the block system allows it to fit into their schedule without missing their commitments on campus.”

Now Cornell has launched a core curriculum called the Ingenuity program that expands and formalizes efforts to encourage and enable students to take advantage of the block structure by encouraging more meaningful extracurricular, enrichment, and vocational experiences. That includes a requirement that students engage in at least two experiential learning projects, such as an internship, academic research, civic engagement, creative endeavors, or off campus study, and by supporting such endeavors with financial support of, on average, $3,500 per student, as well as seminars on writing and civic engagement and a capstone portfolio in which students reflect upon their time at Cornell by pulling their experiences together and expressing what they have learned about themselves and where this is pointing their post-college plans.

The block system and a student-teacher ratio of 13 students per faculty member enable great depth of instruction, particularly in STEM subjects, Brand says. “Our students overwhelmingly report when they go to grad school that it is not as hard as they thought, and our med school acceptance rate is nearly twice the national average, as the block system makes our students so much more comfortable with in-depth research,” Brand says.

Flexibility

Levine notes students are increasingly demanding flexibility as to when and how they receive higher education, and he also notes that online providers are better able to offer such flexibility. WGU takes this even further with its competency-based model, which ties degree progression to demonstrated mastery of a subject rather than semesters, quarters or units. This allows flexibility in progression and allows students to tailor education to their needs.

“Grades are simply a function of how much we as different individuals are able to learn in a set amount of time, right?” Pulsipher says. “That is a nice comparative tool, but not very effective when it comes to the differences by which individuals approach learning, such as varying competencies they bring or their capability for mastering certain subjects, which varies a lot in our case, where you’re serving working learners who have a lot of non-academic experiences from which they can draw knowledge. The way we’ve approached that is we have a subscription-based consumption model where you pay a subscription tuition for each six-month period and complete as many courses as you want as you earn credits.”

Some WGU students have finished a bachelor’s degree in one term, Pulsipher says. “This may be someone, for example, who’s already been working as a software developer for 10 years in the industry,” Pulsipher says.

In some cases the educational product is becoming inverted. “Many students are entering the workforce early with the hope of pursuing education down the road,” says Brandon Busteed, chief partnership officer and global head of Learn-Work Innovation at Kaplan. “There are 18-year-olds going straight to work at Walmart because they know they can get their college degree for free with Walmart’s support. And they’re making a tradeoff, thinking ‘I’m not going to do the residential college, I’m going to live at home and make some money and get a degree.’ It’s a debt free college model—why not consider it?”

Innovation

Fostering innovation is another area where institutions will need to improve, many interviewed noted. Boards need to become more involved in strategic decision making, Busteed says. One way to foster this is to structure board components that address this.

“Boards need to ask the question: where does innovation live?” says Busteed. “Has it been given a name? Has it been given a purpose? Is there a reason to think that we’ve institutionalized it as a behavior as opposed to just an accidental occurrence? One thing I’ve always admired about Wake Forest University that I use as an example is that when [former President] Nathan Hatch got there, he established a board committee on innovation. And so innovation became a focal point at Wake Forest, including through creation of a VP of innovation role in his cabinet. And this wasn’t just to handle the tech transfer function. This was thinking about innovative moves of any kind, such as new revenue sources and new types of students.”

It may take experimentation before individual institutions find their way in the new, more complex landscape, notes Levine. Universities must also embrace institutional flexibility, Levine notes. There is little point in experimentation and innovation if there exists little capacity to change. This may be particularly the case at the departmental level, Levine says, and may require advocacy with often powerful faculty bodies.

“And what I’ve told presidents is—and I’ve been very frank with them—‘scare the hell out of your faculty,’ ” Levine says. “Tell them the truth about the future and the consequences of failing to respond to changes in demography, the knowledge economy, and a technological revolution. And then invite them to join you and plan the future.”

At ASU, innovation includes process innovations. “We don’t just want the faculty member to be innovative in their science or lab or in their creativity in philosophy or whatever,” Crow says. “We’ve focused on the institution being innovative in how do we become of greater service? How do we lower the cost of delivering the degree? And how do we provide people faster speeds to get to their degrees? How do we allow people to double major, triple major, quadruple major, all of which requires us to be innovative. And so we have taken it on at the mission. We and a few other higher education institutions are prototypes of a new type of institution, a national service university.”

Institutions also may engage in innovation through product segmentation to a greater degree than in the past. As noted in a May/June Trusteeship article, Unity College in Maine has reorganized its educational offerings around distinct business offerings and learning modalities aligned with different student demands. The shift has led to increases in enrollment and a strengthened bottom line.

Pulsipher notes online education has highlighted the increased availability of other educational content. “It immediately exposed the fact that students can access the best content available, just like they can stream Netflix or have a Spotify playlist,” Pulsipher notes. “At WGU, we’re investing in technology that is sourcing and making available to students all the best learning resources out there. And that is a huge marketplace. We’re looking at which of that content is going to increase the probability that students are going to master the subject material, so that they can better prepare to actually demonstrate competency on the criterion-based assessment.”

Pulsipher says that additional research into learning effectiveness may further such efforts. “Some faculty at colleges may lecture three days a week, use curriculum they have been using for years, and may not have really assessed whether the lectures fundamentally increased the learning of the student, ” he notes. “Students may have learned the material in study groups or tapped into other online resources like Khan Academy or a YouTube university. We’re actually specifically identifying whether or not students learned from the learning resource produced by each WGU faculty member and asking what is increasing the ability of an individual student to master concepts.”

More Alignment, Support and Counseling Services

To retain students and earn their support, colleges and universities will need to improve educational alignment, counseling, and support services, several interviewed said.

Many institutions are seeking to ensure pipelines of students by developing precollege programs for high school students, Busteed notes. And, according to Wyner, of the Aspen Institute, dual enrollment in high school and college is also likely to increase.

“Finding different ways of working with K-12 is another huge opportunity that some colleges are taking advantage of,” Wyner says. “Nationally, somewhere between 15 and 20 percent of all community college enrollments are their high school students. I was recently with some community college presidents in Texas, and one was telling me that more than 50 percent of their enrollment is high school students.”

And at George Mason University and Northern Virginia Community College, students enter the community college duly admitted to both the community college and the four-year institution, Wyner notes. “If you move towards co-ownership of a student with another educational institution, you are much more willing to figure out what the advising function should be not just at your institution, but throughout the student’s journey, and then apply responsibilities and resources accordingly,” Wyner notes.

Through a program called Direct Connect, for example, dual enrollment students at Valencia Community College and feeder high schools progress to Valencia and then to a major Florida regional university, UCF. “At Valencia, 50 percent of students who take dual enrollment courses at their feeder high schools come to Valencia, whereas at many other schools, it’s much lower, around 10 percent,” Wyner says.

Better pathways are also needed between community colleges and private liberal arts institutions. Improving transfer pathways from public two-year and private four-year institutions could enhance the financial health of four-year colleges while raising baccalaureate attainment for community college students, says Loni Bordoloi Pazich, program director for institutional initiatives at the Teagle Foundation, which is supporting efforts to improve such alignment. Such pathways can offer community college transferees soft skills that complement community college technical skills, the well-rounding provided by liberal arts institutions, and a lower cost program (given it is only two years). Liberal arts institutions receive a more diverse student population, more students, and students who on average perform as well or better than “native’ four-year students.

“Research shows that associate degree completers are successful post-transfer at four-year colleges and have rates of baccalaureate attainment that exceed ‘native’ students,” Bordoloi Pazich says. The Teagle, Arthur Vining Davis, and Davis Educational Foundations have been collaborating to establish transfer admission guarantees across several states.

Counseling is a critical weak point in the entire higher education system, says Anthony Carnevale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce. Busteed and Levine say that several online educators are focusing on the counseling and other services that students need.

WGU, for example, invests in program mentors who provide one-on-one assistance to students, Pulsipher notes. “Every student, from the day they start to the day they graduate, has a mentor,” Pulsipher says. “That mentor has a master’s degree or higher with eight and a half plus years of experience in their field of study, and they are available to specifically shepherd that individual along—to help deal with not only academic needs, but also all the life disruptions that tend to be the reason students drop out. This is the most important reason our students stay. They say in our surveys, ‘I had faculty that encouraged my dreams and aspirations.’ ”

WGU also invests heavily in program curriculum development. “We are continually updating and investing in our program and curriculum design to ensure the freshness of our degree programs, and the curriculum that comprise them is holistically revamped every three years or less,” Pulsipher says. “If you want to ensure that education is a pathway opportunity, it better be timely, relevant, and high quality.”

WGU introduced an education readiness program through the creation of WGU Academy, an endeavor that launched just over three years ago.

“WGU Academy is designed to effectively improve the read- iness of learners, especially those who have never learned at a post-secondary level or who may have previously attempted college but were not able to be successful. It particularly focuses on things like learning how to learn, or efficiency, preparing individuals to apply reasoning and analytical capability to the post-secondary level coursework that they’ll be doing. Through WGU Academy, we found that individuals who actually complete Academy and then matriculate to WGU do substantially better than our student population as a whole. This was simply a recognition that some of the barriers of our students have nothing to do with affordability, or even prior college experience. It was, ‘do you have the capacity to learn and, if not, what is required?’”

Also missing from much traditional higher education is curation of how education relates to advancement in careers, upskilling in professions and career transitions. “Many ed tech providers are working to provide this. It is a large opportunity for higher education and one that, if missed, will be assumed by others,” says Carnevale.

Companies like Naviance, Overgrad, and Xello, big providers of college and career preparatory online platforms in K–12 education, for example, have gotten bigger. “They’re very much in this game and have moved to selling work-based learning that links high school, colleges, and careers,” Carnevale says. “The problem for them is that we know that counseling doesn’t necessarily work unless it’s face to face, especially with less advantaged kids.”

Such services and alignment can feed into improved retention, which will become more important for colleges and universities as the available body of students declines. “Increasing student success and retention would allow institutions to maintain more enrollments out of the same numbers of students,” says Carleton College Professor of Economics Nathan Grawe, author of 2018’s Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education. “We see almost embarrassingly high attrition from the first year to the second, and sometimes for the second to the third as well.” Grawe notes retention is particularly relevant for disadvantaged minorities.

Better alignment with long-term student, and not just employer, interests will also become increasingly important, the Aspen Institute’s Wyner says.

“There are lots of examples where industry, once they’ve got people in entry level jobs, want to keep them there as long as possible,” Wyner says. “But community colleges and universities can, and should, ensure that students have both the technical and adaptive skills to move ahead over time, and ideally stay in touch with students to help them obtain additional higher education if needed for career advancement.”

Equity

As noted in the first College of the Future story (Trusteeship, Septe./Oct. 2022), the higher education student body of the future will be less affluent and more diverse. The stakes are enormous for the country. Raising educational attainment among lower-income and minority adults to equal the attainment distribution of middle- and higher-income adults, and simultaneously raising educational attainment among racial and ethnic groups to match attainment among White adults, would result in annual public benefits of more than $950 billion, Carnevale says.

Addressing equity is a logical subset of an enlightened university’s attention to problem solving, says Freeman Hrabowski, III, until recently president of University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), a state university in Maryland that has transformed into an R-1 research institution while educating a high number of disadvantaged minorities in STEM fields.

Generalizations of all sorts should be replaced by data, Hrabowski says. “There’s no such thing as ‘the students’ at a university. They are all these different ethnic groups, they are different racial groups, they are different ages, they are from different parts of the world. And so disaggregating the data can stop the generalizing across the board and can help institutions become more effective in working with different types and groups of students. We try to understand the background of a student of any race, who has a reasonable chance of succeeding at UMBC. We look at everything from test scores and grades to attitude and rigor of high school work. And we’ve done that over three decades now.”

Hrabowski says, for example, that analytics can help identify, beyond the top-performing minority students that are coveted by every institution, those students who have a greater chance of success at UMBC—and those who do not. “We found, for example, that minority males who had very high test scores, even perfect test scores, but who had mediocre grades in high school tended not to do well in engineering and science, because they are accustomed to being super-high achieving on tests,” Hrabowski says. “They got 800 math SATs, but they don’t work hard. And they have an attitude problem.”

On the other hand, children of immigrants of all races do better. “The international influence at UMBC is very strong: 60 percent of our students of all races have at least one parent from another country,” Hrabowski says. “The point is, there’s an intensity that first generation Americans have.”

That leaves the challenge of the mass of disadvantaged minority students who are not immigrants, high performers, or affluent. Succeeding with this group of students takes effort, Hrabowski says.

Part of the work involves developing pathways for K–12 students from inner city Baltimore “by having well qualified teachers and Sherman STEM Teacher Program scholars who will prepare them for places like UMBC,” Hrabowski says. “Board members and donors have donated more than $38 million over the years, focused on producing first rate math and science teachers for those schools.”

UMBC has also redesigned coursework so that more and more diverse students can succeed in science and engineering courses. The model is being nationally replicated through similar programs at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Pennsylvania State University, and UC Berkeley, with foundation funding.

Reducing the debt burden upon lower income and disadvantaged minority students is critical to enable them to buy homes, marry, and pursue graduate education that will further their development, NCA&T’s Martin says. “We have an investment strategy to support our students so that they have less need to borrow funds and we manage our costs to attend by controlling tuition increases and fee increases,” Martin says. “The debt of our students at graduation has been declining every year for the last eight years. That’s because we’ve raised more money, we’ve managed costs, and we’ve limited debt burden of the university and passed on costs to our students. But that also means that we have had to be much more proactive in pushing our legislature and our governor to use the system to fund the important aspects of the needs of our university, as we look to the future.”

Ultimately, equity may mean meeting each student where he or she is in terms of learning needs.

“Some people need more input than others,” says Aaron Thompson, president of the Kentucky Council on Postsecondary Education (Ky CPE). “We are working within the schools and are targeting communities to get them to a point where they understand they can go to college and they can afford to go to college.” That has included increasing scholarships and financial aid to minority students so that they do not run out of money once they enroll.

The Ky CPE also has worked since 2016 to reframe remedial education so that students receive credit for [those classes] and can see progress toward a degree. “In addition, the council has supported such classes with wraparound services, tutoring, mentoring, all of those pieces, and we have also said, ‘we have a high expectation of you that believe you have the knowledge to do college work, and you can do these courses,’ ” Thompson says. Those steps have helped increase the completion rates of minority students compared to the overall population of students, Thompson says.

Equity and social progress alignment is also receiving the official imprimatur from a joint collaboration between the American Council on Education (ACE) and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, for a new set of classifications that recognizes equity issues. To be launched in 2023, the Social and Economic Mobility Classification will reflect an institution’s commitment to success in enabling social and economic mobility nationwide while effectively serving a diverse, inclusive student populace.

Equity also means ensuring key college experiences are enjoyed by all. “At Simmons University, we want to ensure experiential equity, that is, ensuring all students at Simmons are taking advantage of the resources and the excellent education provided, not just those at the top or at the bottom, but all students from diverse backgrounds,” says Lynn Perry Wooten, president of Simmons, a Boston-based liberal arts institution, that provides undergraduate education to students who identify as women but graduate education to all genders. “We also look at how we can help women address the special challenges many face, such as COVID, which has been called the she-cession, rather than recession, given the way it set back many women because they had to leave work to care for others and because of COVID’s disproportionate effect on careers in which women are concentrated.”

Wooten, Simmons’s first African-American president, aggressively uses data to address equity and inclusion issues of all types, she says. “For example, the data told us that we had a diversity problem in nursing—there are not a lot of nurses who are people of color,” Wooten says. “We have implemented a Dotson bridge and mentoring program that identifies students who need to belong to that community. It’s coaching and mentoring with nurses who look like them. And it is additional academic support, especially for the science classes in the heart of nursing labs, so that we can identify which classes are harder and which ones they need academic support for and provide that extra support as well as mentors and counselors.”

Public Discourse

A need that colleges and universities will have to address mentioned by many interviewed is increasing public discourse and social cohesion. To work on improving public discourse, institutions will have to practice such traits at home, Hrabowski says. He notes that UMBC operates under a shared governance model, “which means ‘it’s not us versus them’ at the system level or at the campus level,” Hrabowski says. “Faculty and staff and students and administrators are working together to solve the problems that we’re talking about. That’s very, very important. We weaken ourselves when it’s us versus them. We work to have governance where we share the responsibility and then the buck stops with the president. We are also fortunate that our University System administration and our Board of Regents are very supportive and enter into the discourse with us.”

Campus culture and cohesion will be critical ingredients in higher education winners, Cornell College’s Brand says. “Those will be the schools that have the most motivated alumni and friends to invest in those institutions,” Brand says. “I think the schools with the healthiest cultures are going to do really much better, whereas schools that are angrier—where there’s warfare—I think that culture will be very detrimental for those schools. That’s why we’re so focused on culture at Cornell, because schools where people feel connected and where faculty, staff, and students find meaning and satisfaction in their work and study—students know that connection, and I think it makes a difference in those who come and then the quality of the experience they have when they’re on campus.”

Preserving education in the humanities in the face of a shift toward STEM and professional instruction will be important to maintain democratic and civil discourse, Bordoloi Pazich says.

“The future of the humanities—which are so important for preparation to participate in our democracy—lies in general education as students increasingly turn to pursuing professionally oriented programs of study,” Bordoloi Pazich says. “We have seen tremendous promise in revitalizing the role of the humanities in general education using the “Cornerstone” program model at Purdue [to make the humanities an integral aspect of a coherent general education program]; [the Teagle Foundation is] now supporting adaptations nationally through our Cornerstone: Learning for Living initiative co-sponsored with National Endowment for the Humanities.”

The Time is Now

If there was a single theme that came through from higher education leaders interviewed for this story, it is that after COVID forced higher education institutions to do more than many trustees would have thought possible and as the demographic cliff of declining undergraduate enrollment looms only a few years away, the time for pedagogic reexamination and reinvention is now, and there is no time to spare.

Lafayette’s president, Hurd, who joined the college last year, “is upping the tempo on everything in the place,” says Lafayette trustee Mendez.

“In the pandemic, we went through a massive disruption and adapted successfully,” Hurd says. “Then you realize that part of what we built and the muscle that we don’t want to lose after the pandemic is the ability to really listen to each other well and be able to be nimble when needed. If we don’t continue to be nimble, and frankly, both communicate well and be inclusive at the same time, then we’re not going to make the best decisions for our community. I’m a big believer, especially on issues such as our budget, that the budget is a value document and if we don’t actually have conversations with our community about it, then we’re not reflecting those values the way that I’d like us to.

“This past summer, we formed our first ever community-wide diversity, equity, inclusion committee and we put in place for the first time in a long while a community-wide budget committee,” Hurd says. “And I know when I say ‘committee’, people are going to think, ‘Oh, that’s not effective or efficient.’ But when I got here, we had many different diversity plans, including at the departmental level, often done, I gather, in silos. There was definitely not a common vision, or a common strategy for doing really important work on our values and how we show up for each other. And now we have four faculty member colleagues, four staff member colleagues, and two other staff members providing important support looking at the budget and diversity, equity, inclusion issues, in a much more synergistic, holistic, and, frankly, much more nimble fashion.”

Trustees in particular should work with university executives and other stakeholders to examine such issues now, Crow says.

“The trustees have got to demand change and to stop accepting things as they are,” Crow adds. “Every time the administration says something like, ‘the faculty won’t do this, they won’t do that’—that’s not true. Our faculty have voted for 35 new schools and initiatives, they’ve eliminated 85 academic units, they’ve changed the curriculum, they’ve changed the design, and thousands of our faculty members have been trained in advanced, technologically based learning and thousands of courses have been built by our faculty members. And so this notion that somehow the fact that culture is a fixed thing, and the trustees are just supposed to accept it…well, they don’t have to accept it. Trustees need to drive innovation. Or if they’re not going to drive innovation, they need to not block innovation.”

David Tobenkin is a freelance writer based in the greater Washington, D.C. area.

Editor’s Note: This article continues from the September/October issue of Trusteeship magazine and examines other aspects of the college of the future: The College of the Future, Part 1

RELATED RESOURCES

Trusteeship Magazine Article

The College of the Future, Part One

Reports and Statements

AGB Board of Directors’ Statement on Innovation in Higher Education