The new edition of this essential guide to Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) will be available for purchase and e-book download (for AGB members) later this month. Excerpted below are brief selections from the text which AGB feels may offer helpful guidance for board members and academic leaders navigating the rapidly evolving COVID-19 crisis.

[From the chapter “Enterprise Risk Management: A Guide for Administrators.”]

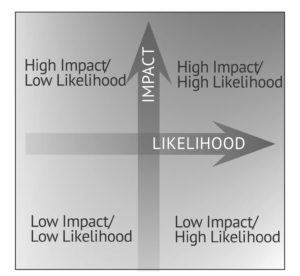

Colleges and universities use an array of different tools for assessing risk, from simple heat maps and worksheets to complex modeling spreadsheets and scenarios. For example, the senior risk committee of an institution with limited resources, using a simple heat map (see graphic below), can start by writing specific risks on sticky notes and placing the notes in the quadrant of a heat map to reflect the impact and probability of the risk. Placement of the sticky notes depends on administrator’s answers to the questions: “How likely is it that this will occur on our campus?” and “How bad will it be if it does?” The goal of this exercise is to identify the risks that belong in the “high impact/high likelihood” quadrant and begin risk mitigation plans on these risks first.

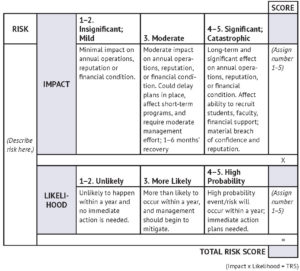

For institutions with more resources, a more complex risk assessment method involves the use of a scoring tool. (See graphic below; for a more advanced risk scoring tool.) By assigning risks an Impact and Likelihood score and then multiplying them, administrators can compute a total risk score (TRS) for each risk considered. The total risk score, however, should not be a substitute for the good judgment of the senior administration.

While the TRS is a quantitative ranking, senior risk committee members should use their professional judgment to evaluate the ranking, reordering as appropriate and grouping the risks into high, medium, or low (or red, yellow, or green). This kind of ranking process helps institutions spend scarce resources on their greatest vulnerabilities, and not waste time and energy on risks that pose only minor threats to the institution.

The top five to 10 risks should be shared with the governing the appropriate board committee. The president and board chair should decide how the board will engage and conduct further inquiry into each risk. The second 10 to 20 risks should be assigned to department heads and deans with responsibility for developing mitigation plans and reporting regularly to the senior risk management committee.

[From the chapter “Risks to Strategic Direction (and Shared Risks)”]

Standing committees play an important role in working with senior administrators to assess the risks and responses facing the institution. Some risks do not fit neatly within the charter and purview of the standing committees and can be the work of the full board. While the executive committee or the audit committee can address some of those risks, for reasons that AGB’s The Executive Committee describes, the full board—sometimes facilitated through ad hoc committees or task forces—is the ideal place for discussion of shared risks that cross functional boundaries. …

Crisis Response and Business Continuity

To open the dialogue the board may ask:

- Crisis response plan. Does the campus have a crisis response plan, and is it regularly tested and revised? Does it include a communications plan?

- Board communications. Do board members understand their collective and individual roles in a crisis? Are procedures in place to keep them informed during a crisis?

- Leadership contingency plan. Is a plan in place to respond if a crisis is directed at the president, a board member, or the board chair?

- Data recovery. Does the crisis response plan include an evaluation of technology needs to support recovery of data and restoration of all services? Does it include evaluation of campus research to support protection and recovery?

- Business continuity plan. After the immediate crisis has passed, does the institution have a plan to resume instruction and research if it does not have access to some of its core operating assets, such as the physical plant, cash, faculty, staff, or IT infrastructure? Do departments have continuity plans in the event that a crisis disproportionately affects their operations?

Hazing, alcohol abuse, sports scandals, sexual assault, shootings, high-profile tenure decisions, disputes over academic freedom (and academics speaking freely on social media), quarreling boards and presidents, and board member misconduct begin the list of high-profile campus crises that plague higher education institutions. But external events beyond the institution, such as a flood, earthquake, or hurricane can also become crises.[1] So can, if left unheeded, societal trends of shifting demographics, declining state support, and competition from new education providers. A trend is not a crisis, until it is.

Campus leaders should recognize that crises are not predictable but inevitable. A crisis is an unplanned event that has the potential to endanger community members or the institution’s facilities. A crisis can quickly turn into a reputation event, costing the institution hard-earned goodwill from its stakeholders.

It is easy for institutional leaders to think that they are immune from the headline-grabbing, mission-weakening crises that afflict other campuses, but history proves otherwise. Whether the institution is large or small, rural, suburban, or urban, crises do not discriminate. A “cool head, warm heart”℠ philosophy is a principled approach for responding to a crisis. In short, it includes responding to families and the community in a caring manner while adhering to established policies and practices that limit liability and speed recovery.

Many academic institutions spend a disproportional amount of time identifying the risks that could derail or delay their plans and mission. Similarly, institutions spend significant time and energy developing crisis response plans but very little of it testing the plans. If that is the case, boards should encourage flipping the planning and practicing equation. While the institution cannot predict what the crisis will be or when it will occur, the leadership should practice how to respond to a wide range of possible risks. Like training a muscle, practicing crisis response—through a tabletop drill or mock exercise involving community participants when possible—develops the skills and relationships that your leaders will call on when the inevitable occurs, even if they never prepared for that specific crisis.

The complexity and intensity of some of the most prominent scandals to hit higher education require expertise in response that is well beyond any campus.[2] As a faculty member notes, “No campus is prepared for the media spotlight that accompanies a crisis of the size and scope that occurred at Duke University or Penn State. Even the most experienced campus public relations staff need outside help.” The need for immediate responses—via multiple channels—and the viral potential of events and any additional missteps call for specialized expertise beyond the experience and talent of internal staff. Having an external communications firm or consultant familiar with the institution, its culture, and its circumstances can provide much-needed additional support for managing the messages in the midst of a crisis.

The board can play a role before and during a crisis, but unless the crisis focuses on the president directly, that role will be limited. Before a crisis, the board should ensure that a plan is in place and require that it is regularly tested. During a crisis, the board and president must maintain alignment on the response, with the board offering to support the president and senior administrative team as appropriate for the crisis.

After the immediate crisis is over, it is time to get back to business. Unfortunately, that can be challenging when the crisis disrupts critical campus functions. Physical emergencies—such as a violent crime on campus or a natural disaster—may make parts of campus inaccessible or prevent some employees from returning to work. For example, at one institution, campus leaders who responded to a violent crime were surprised that they could not access their administrative or IT buildings until after an investigation was complete.

At a minimum, campuses should have a plan in place for how to return to instruction and research following a disruptive event. This plan should address how the institution will reopen if:

- Part or all of the campus is closed or inaccessible;

- The administration is largely incapacitated;

- Significant portions of faculty are unable to teach;

- Liquid cash is unavailable;

- IT infrastructure is offline or damaged.

Insight: Preparing for A Global Pandemic

The rapid and global spread of a new strain of the coronavirus (COVID-19) in early 2020 provided an opportunity for institutions to test crisis response and business continuity plans. As the coronavirus outbreak spread across the United States, institutions were faced with unprecedented decisions to prevent virus transmission. The pandemic impacted core academic and business activities, as institutions canceled on-campus activities and shifted to remote classes and telework. Many institutions also canceled large events and discontinued extracurricular programs such as athletics and study abroad. As this guide is being published, institutions continue implementing innovative social distancing actions to maintain business continuity during the ongoing pandemic.

Some campuses create plans for combinations of the scenarios above, while others also require their colleges or academic departments to create unit-level continuity plans. Some plans rely on the administrations, faculty, staff, and campuses of neighboring institutions to overcome continuity challenges. The board should encourage the administration to develop and role play such plans.

Insight: Know Where the Crisis Management “A Team” Resides

In hindsight, campus leaders who have lived through headline-grabbing events often acknowledge that stumbles were made immediately after the crisis while the campus team tried to respond and hire a public relations firm with relevant higher education experience—all within hours after the crisis hit. One president commented, “We tried to respond ourselves to the crisis for the first 24 hours, got the B team from a PR firm for the next 36 hours, and then finally identified the A team. But we were three days into the crisis with much damage done before we were truly ready to respond.”

Catastrophic Weather and Climate Change

The increase in catastrophic weather events over the past several years demonstrates the need for institutions everywhere to prepare for a changing climate. To open the dialogue the board may ask:

- Emergency plans. Does the institution have emergency policies in place to keep students, faculty, and staff safe, and to protect the institution’s physical property?

- Continuity and recovery plan. Does our continuity planning address how to respond during a weather emergency, and how the institution will get back up and running?

- Satellite campuses and study abroad. If the institution has remote or overseas campuses, has it also developed plans appropriate to these alternate locations?

- Lending a hand and receiving a hand. If a disaster strikes nearby, is the institution prepared to fill the need for facilities and supplies to support relief efforts? Does the institution know where to turn if resources are inaccessible in a weather crisis?

- Geographic and economic impact. What are the likely long-term impacts of climate change to the institution?

Institutions must be able to respond to the impact of catastrophic weather and other natural disasters. While institutions once needed only to focus on being prepared for extreme weather common to their geographic region, they now have to adopt a general posture of preparedness. From fires and floods to hurricanes and landslides, institutions must be prepared for extreme weather events.

Generally, there are two kinds of extreme weather events: those for which there is advance notice and those that occur without warning. For foreseeable events like wildfires and hurricanes, institutions have time to mobilize. In contrast, for sudden events like floods and tornadoes, the only way to mitigate the risk of these events is to prepare beforehand.

Institutions should have emergency plans for all types of weather events that might affect them. It is also important to conduct tabletop exercises to prepare staff for emergencies, as well as to identify gaps in policies and procedures.

Over the longer term, institutions should expect disruptive weather events to become increasingly frequent and severe as the effects of climate change become more pronounced. That trend will harm the institution financially: property and flood insurance are likely to become more expensive, and facilities will be more difficult to maintain. For some regions, climate change is likely to cause long-term negative economic damage. Boards and senior administrators should consider how climate change will affect the institution’s operations in both the short term and the long term. …

[From the chapter “Risks to Institutional Resources.”]

Boards are tasked with ensuring that institutions have adequate resources in place, including financial, human capital, facilities, and information technology resources. Given the breadth of these resource areas, no single committee can oversee all of them. Instead, various board committees oversee aspects of financial planning, strategic employment practices, maintenance and master planning, and information and cybersecurity strategy.

Risks in these resource categories are constantly changing, and boards must continue to ask how the institution is adapting to global changes and trends that affect higher education. While administrators are tasked with operational aspects of managing these resources, board members will look at resource risks strategically and hold the administration accountable for having programs in place to advance the institution’s mission and objectives. …

Information Technology

To open the dialogue the full board may ask administrators about:

- Information technology (IT) strategy. Does the institution have an information technology strategy? Does it reflect the institution’s core values and strategic plan?

- Protection. Do agreements with partners properly protect intellectual property rights and other institutional values (such as privacy and nondiscrimination)?

- Privacy. Do IT staff members regularly assess changes in privacy and other federal and state compliance areas?

- Cybersecurity. Does the institution perform regular IT security risk assessments and report findings to the board?

- Regulatory risk. Is the institution ready for emerging data privacy regulations from the European Union and elsewhere?

- Data sharing. Does the institution have a consistent approach to contracting with cloud vendors? Is the institution clear on who owns data stored with those vendors and who will bear the cost in the event of a breach?

- Accessibility. Does the institution have an electronic information technology (EIT) accessibility policy? Are the institution’s websites accessible to individuals using assistive technologies?

- Missed opportunities. Is the institution taking enough risk with its IT strategies? Are there opportunities to enhance the educational experience that have not been considered?

Over the past 20 years, information technology has evolved from being an operational support function for financial reporting and student records to becoming an integral part of teaching, research, and service. Data and cyber assets should be counted as one of four major assets (human, facilities, financial, and cyber) under the board’s fiduciary responsibilities for institutional assets. The risks of loss or diminution of any of these assets is an important part of the institution’s risk management strategy.

Institutions benefit from having IT experts serve on their boards. They bring a wealth of experience and knowledge of trends in a rapidly changing industry. While IT issues in higher education and commercial businesses are often similar, the differences are also substantial, and boards need to recognize the differences as well as the commonalities. The culture of higher education is one of transparency, openness, and collaboration. Businesses can operate secure and closed systems, while colleges, universities, and foundations serve broad communities from students, alumni, and donors to researchers and faculty. Small to midsized academic institutions have correspondingly smaller staffs, with members who are often generalists without the level of specialization or access to the top vendors that people who work in large corporate (and some large research university) IT departments have. Boards that understand these contexts and issues of scale are best positioned to help their institutions identify, assess, and mitigate IT risk.[3]

Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity poses a prominent risk for institutions of higher education. The nature of open networks, extensive systems, “creative” users, and sensitive data can generate the temptation to engage in mischievous and/or criminal actions. Unlike other industries, the openness of higher education networks means that a compromise in one place can impact the whole enterprise. Educational institutions have increasingly become targets of cyberattackers, who seek access to everything from email accounts and human resources records to medical information and research data. And the recovery, legal advice, and forensics work required to respond to a data breach are extremely expensive.

For cyber risks, the 80/20 rule is that institutions should allocate 80 percent of their resources to developing and testing cybersecurity systems (including on-campus and mobile computing) and 20 percent of their resources to responding to the significantly reduced risk of a major breach.

The board should ensure that policies are established and updated periodically, that testing is regularly conducted and reviewed, and that appropriate resources are invested in the security of computer systems and data. With the rise in prevalence of phishing and malware attacks, institutions should also train all employees with access to sensitive data–including human resources, finance, and other administrators—as well as research faculty on how to detect and avoid such scams.

Data Collection, Integrity, and Analysis

Within the IT function the emphasis on decision making is shifting from technology to information. IT discussions in higher education now include not just hardware and software considerations but also more intangible issues, such as privacy and instructional learning methodology.

Data analytics supports academic missions and also increases institutional risks. The trend toward collecting and analyzing information on potential students, current students, and alumni offers tremendous opportunities and significant risks. Identifying what data to collect, how to analyze them, what privacy and transparency policies should be in place, and whether the campus is prepared to use the analysis are the risks and opportunities of the new frontier of data analytics. The board should confirm that the institution has a privacy policy on the collection and use of such data and that the policy is made readily available.

Insight: Data Analytics Support Missions but Raise Privacy and Data Security Risks

The power of data analytics that is sweeping the business world has the potential to change student health services, academic advising, and alumni relations. Many campuses collect data on a student’s class attendance, number of meals eaten in the dining hall, library visits, and attendance at sporting events. Campus administrators can analyze such data and, using predictive modeling techniques, potentially identify students with substance abuse problems, those most likely to drop out, and/or those likely to become loyal and generous alumni. Questions that the board should ask and that should be answered include:

- Does the institution have a data analytics strategy?

- Is the institution collecting the right data?

- Is the institution willing to act on the data for the good of the institution?

- What is the institution’s policy on data privacy?

Emerging Risk: New Regulations

From data collected through admissions applications and student and employee records to information from alumni and donors, institutions frequently collect and retain information about individuals related to the institution. Because institutions are typically decentralized, without a single strategy that governs all data, many institutions struggle to fully grasp how much data are retained and how and where they are stored.

With the passage of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), organizations with data on consumers are facing a new kind of compliance regime requiring a strategic, end-to-end approach to data privacy that allows consumers to delete that data or take them with them to another provider.

For now, these regulators are not focused on higher education. European Union regulators are focused on marketers, and the CCPA law generally does not apply to nonprofit organizations. However, the day may come when these sorts of laws are commonplace, and institutions should be prepared. To comply with this new type of law, institutions must track their data on students and other consumers, knowing everywhere that data go and where they came from to begin with. Some institutions are drafting privacy policies that are more stringent than existing privacy regulations. This ensures that they are prepared for future regulations while also building a reputation for protecting their students, faculty, staff, and community.

One type of data potentially impacted by these new regulations involves admission and recruiting information. If someone from the European Union or California asked an institution to delete admissions data on them, how would the institution respond?

Data Sharing and Cloud Vendors

Institutions must be vigilant when contracting with cloud vendors to preserve appropriate rights to institutional data. Many vendors want their customers’ data because that allows them to provide value to all those customers through better analytics and benchmarking.

Institutions should contract with cloud vendors in a centralized manner, with all contracts vetted by IT and legal counsel. Industry standard language may not apply to higher education, so institutions should negotiate contracts that allow them to comply with the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and other applicable rules.

It is also important to vet the data security practices of vendors. That includes reviewing their practices for security data in transit over the internet as well as data at rest on their servers and in backups. Institutions should also request audits of the physical security of the vendor’s infrastructure, as well as the security of their application.

It is also important to understand, in the event of a breach, whether the vendor is required to notify the institution and who is responsible to pay breach notification costs and other related expenses.

Web Accessibility

In recent years, Electronic Information Technology (EIT) accessibility has become an important topic as regulators and plaintiffs’ attorneys have pursued institutions with outdated and inaccessible websites. Federal law—specifically, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act as well as the Americans with Disabilities Act—requires institutions to provide students with disabilities, and in some instances the general public, with access to electronic information. Many states have related requirements that apply to colleges and universities, some only to publics but others to all institutions in the state.

To succeed at EIT accessibility, institutions should adopt an accessibility policy and implementation plan. Designating an EIT accessibility coordinator and creating guidelines for faculty and staff to ensure web-based content is accessible is also key.

Vendor contracts should guarantee that EIT products meet these same accessibility requirements. Vendors should provide a voluntary product accessibility template (VPAT) for their products, identifying the level of support those products have for federal accessibility requirements. Legal counsel should vet contracts with EIT vendors to ensure that those vendors are obligated to remedy any accessibility shortcomings that arise and also, ideally, to have the vendor indemnify the institution in the event of a lawsuit or regulatory action involving the product. Multiple institutions should also consider procuring their products as a group to have more leverage with vendors over accessibility support.

While audit, governance, and executive committees are common to all boards, institutions also maintain board committees that provide oversight of the core student experience: academics and campus life.

These academic affairs and student life committees guide and support the mission of the institution—teaching, research, and service—and ensure an overall positive student experience. It is not the role of the committees to manage these functions, but it is their responsibility to understand, question, and ultimately support the direction set by the institution’s strategic plan and implemented through its annual operations. Committee oversight requires strong knowledge of potential risks.

Online Education

Disruptive innovations in teaching and learning have further complicated oversight of educational quality. In the past, instructional strategy meant a faculty member decided whether a course would be better taught as a seminar or lecture. Now, instructional strategy might encompass not only lectures, seminars, labs, internships, externships, and service learning, but also online learning, online program managers (OPMs), massive open online courses (MOOCs), social media, and the like. And there are risks at both ends of the blended learning continuum. Some universities—sometimes driven by the board—are rushing to participate in OPMs without a full evaluation of how they fit within the institution’s instructional strategy, broader strategic plans, brand, and overall financial picture. Other (often small, independent) colleges are choosing to downplay online learning opportunities rather than getting ahead of the competition. In addition, all institutions must recognize that online learning and institutional websites have to meet accessibility standards of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Insight: The Evolution of MOOCs, OPMs, and Their Impact on Education

Massive open online courses (MOOCs) rose in the early 2010s as a less expensive learning alternative that connects instructors with online learners from all over the world. The New York Times designated 2012 “The Year of the MOOC” as such institutions as Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford University, and Google developed platforms to offer courses online, typically at no cost.[4]

In 2019, however, a Google search for MOOCs invariably suggests the search query “the MOOC is dead.”[5] Some MOOCs no longer exist, while some have had to cut costs drastically in order to survive.

As MOOCs have declined, OPMs (online program managers) have grown. Most online degree programs in 2019 were delivered through OPMs, which are companies that specialize in online course design, implementation, and delivery. While OPMs were ideal partners for universities as they sought to increase online enrollments—and tuition revenues—most partnerships failed to increase margins or reduce costs. OPMs often take a large percentage of revenues for marketing and administrative support. Some institutions are evaluating the merits of developing OPM capabilities in-house, weighing the significant investment with the potential long-term return.

The promise of education technologies has met the reality of higher education finance and the challenges of change. It has been a bumpy road for many institutions, and the outlook is just as trying with the release of promising new education technologies each year.

To some degree the greatest risk of technology-enabled education is an emerging risk: Will the institution be ready for whatever disruptions come next? Virtual reality courses, augmented reality assignments, artificial intelligence-aided instruction, and countless other education technologies are mostly still ideas, not reality. Will the institution be able to evaluate whether the next development in educational technology is a fad or a disruption? Will it be prepared to innovate on its instructional model to take advantage of new technologies? These are questions without easy answers, but they are crucial ones to ask as technologies promise to change how students learn.

[1] For additional resources from AGB, see:

- Julie Bourbon, “University of lowa Flooding: The Expected and the Unexpected,” Trusteeship, September/October 2008.

- Lyn Trodahl Chynoweth, “Creating Solutions in Times of Crisis,” Trusteeship, November/December 2011.

- Lawrence White, “Governing During an Institutional Crisis: 10 Fundamental Principle,” Trusteeship, January/February 2012.

- Terrence Mactaggart, “Leadership in a Time of Crisis,” Trusteeship, July/August 2019.

- Joseph A. Brennan, “Object Lesson: The Crucial Role of Trustees in Facing Crisis,”Trusteeship, July/August 2017.

- Steve Dunham, “Crisis Management and the Law,” Trusteeship, November/December 2019.

[2] For additional resources from AGB, see “When Governance Goes Awry: What are the Takeaways?” Trusteeship, September/October 2012.

[3] For an additional report from AGB, see:

- Stephen G. Pelletier and Richard A. Skinner, “Technology in Context: 10 Considerations for Governing Boards of Colleges and Universities,” 2010.

- Michael Hites, George Finney, and Joseph D. Barnes, What Board Members Need to Know About Cybersecurity, 2018.

- John O’Brien, “IT: The New Strategic Imperative,” Trusteeship, March/April 2018.

- Eric Denna, “Higher Education’s Return on Information Technology,” Trusteeship, special issue 2015.

- Angel L. Mendez, “Need IT With That? How one Board Effectively Oversees Technology,” Trusteeship, special issue 2015.

- Stephen G. Pelletier, “Taming ‘Big Data:’ Using Data Analytics for Student Success and Institutional Intelligence,” Trusteeship, special issue 2015.

[4] Laura Pappano, “The Year of the MOOC,” New York Times, November 2, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html; “The Future of MOOCs Must Be Decolonized,” EdSurge, January 3, 2019, https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-01-03-the-future-of-moocs-must-be-decolonized.

[5] MOOCs Are Dead—Long Live the MOOC, Wired, August 2014, https://www.wired.com/insights/2014/08/moocs-are-dead-long-live-the-mooc/; “The MOOC Is Not Dead, But Maybe It Should Be,” Wonkhe, March 4, 2018, https://wonkhe.com/blogs/the-mooc-is-not-dead-but-maybe-it-should-be/.