Opinions expressed in AGB blogs are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the institutions that employ them or of AGB.

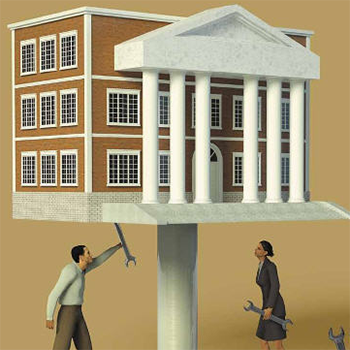

The November meeting of AGB’s Council of Board Chairs focused on the challenges that the environment of volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (VUCA)[1] present to effective and strategic shared governance of America’s colleges and universities.

The session began with a presentation by Council Ambassador David Maxwell, PhD, proposing the essential institutional characteristics necessary to survive and thrive in a VUCA world:

- Agility: the ability to move quickly when necessary;

- Flexibility: the willingness to think and act differently as conditions change;

- Responsiveness: for example, to changing demographics in the student pipeline, a changing financial environment, or changes in the policy environment (federal, state, and local);

- Strategic: a focus on the long term—where are we going, why are we going there, and how are we going to get there?

- Data driven: decisions based on verifiable, concrete information rather than data-free assumptions or “this is the way we’ve always done it”;

- Relevance: relevant to student aspirations and interests, to workforce needs, to community needs, to the needs of a civil society;

- Willingness to take risks: No organization moves forward without the willingness to take careful, well-thought-out risks; this also means a willingness to fail (and learn from the failures).

Maxwell said that the VUCA environment requires that we often need to make decisions with a speed that has not been typical of higher education historically. He noted that some board members (and presidents) become frustrated with faculty participation in shared governance because they feel it impedes the process. At the same time, when faculty members hear from the board or the president that “there’s an urgency to this decision,” they interpret it as code for “so we don’t have time for you to be involved.” Both of these perspectives are not uncommon on the nation’s campuses (often with evidence to support them), and it is important for boards (and presidents) to recognize them and find ways to address them.

Maxwell then proposed a series of criteria for effective shared governance in a VUCA environment:

- “Collaborative/parallel” shared governance rather than “serial” shared governance: Historically, many of the decisions subject to shared governance involve consultation and recommendations from a subgroup of one constituency (for example, faculty) throughout the faculty and administrative hierarchy and ultimately to the board—which can take an amount of time that is simply unacceptable in the VUCA world.

- An effective, alternative approach is “collaborative shared governance” in the form of working groups or task forces comprising appropriate representation of relevant parties, charged with proposing the options for addressing a particular issue and/or making a decision and presenting the relative advantages and disadvantages of those options to the president and/or board for a decision.

- Strategic/anticipatory

- For boards and presidents who stay current on higher education issues, there are very few things that can happen on a college or university campus that should surprise them—though they may well be surprised when they happen.

- Maxwell noted that a crisis is not a good time to figure out what you’re going to do about it, and who’s going to do it; it’s also a terrible time to find out your shared governance isn’t working!

- Institutions should engage on a regular basis in scenario planning based on possible futures: for example, what are we going to do if we have a 10 percent enrollment shortfall? What are we going to do if a student group invites a controversial speaker to campus? What are we going to do if a professor says something in class that offends some (or all!) of the students? And, most importantly, what will be the board’s appropriate role (if any) in addressing these scenarios?

- Boards and presidents should be as transparent as possible in sharing their concerns about potential strategic challenges on a regular basis with their campus stakeholders: It helps to avoid telling people the solution to a problem that they didn’t know they had!

- Finding the “sweet spot” between urgency and deliberation: Even in urgent situations, it is important not to lose the considerable advantages of careful, collaborative deliberation involving the parties to shared governance.

- Open and frequent communication: The more that the parties to shared governance are communicating on a regular basis (through appropriate means) with one another, the more effective they can be in carrying out their roles, and the more they will trust one another in those roles.

- Focus on mission and goals: it is vital to avoid getting bogged down in deliberations of decisions and issues that don’t move the institution forward.

- A decision matrix that identifies the respective roles (for example, consults, recommends, decides, approves) that each party to shared governance plays in each type of institutional decision (for example, budget, faculty hiring, administrative appointments, and so forth). Each of the “squares” in the matrix should refer to a brief narrative that explains exactly how that person/group carries out the identified function.[2]

- A Rapid Response Task Force: The RRTF is a small, representative group (perhaps of trustees, senior administration, faculty, staff, and students) that is empowered to recommend a decision to the president and/or board on those rare occasions when extensive consultation and deliberation are simply not possible.

- Liberation from the calendar: Historically, so much of the practice of shared governance on our campuses has been slowed down by adherence to the rhythm of the regular, scheduled meetings of the parties to shared governance (for example, faculty meetings, board meetings, and so forth). There are times when the institutional interest is best served by an intensive schedule of meetings outside of the regular calendar.

Important Questions for Boards to Address in a VUCA World:

- What do you see as your leadership responsibility as a board chair in the VUCA environment?

- How have you changed your practice of shared governance in response to the VUCA environment?

- Are there particular obstacles to effective shared governance in the VUCA environment?

- In this environment, how have you clarified your goals and decision-making as a board?

- In this environment, who do you talk to on your board or at your institution to get clarity on your goals and decision-making?

There was extensive discussion of issues related to the faculty role in shared governance and board members’ relationships with faculty. It is clear that these are pervasive and ongoing issues for many boards.3

- In developing a strategy, or a change in strategy, at what point do you involve the faculty? Don’t you have to get it formulated enough that there’s something to talk with them about?

- If you have those discussions for too long without involving faculty, they will think it’s already been decided.

- It’s important on many issues to bring the faculty in from the beginning, to look at them as equal partners (in the deliberations, though not in the ultimate decision).

- This is where “collaborative shared governance” can be most effective.

- What in the shared governance world should be the relationship between the board, the administration, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) chapter. and the faculty senate?

- It is critical to be clear about items under discussion—who has the authority/responsibility to talk about what?

- It is equally important to be clear about which group(s) have the authority to contribute to decisions on a particular topic.

- It’s important that people bringing issues to the board/president are legitimately representing the views of their constituents.

- It can be difficult for faculty going back and forth between a union and a faculty senate—essential to have clarity on the issues/decisions appropriate to each.

- There was strong support in the discussion for robust communications between the board (and board members) and the faculty, with an emphasis on the need for clear guidelines on appropriate contacts.

- The more people know each other, the easier it is to build the trust that is essential to effective shared governance.

- It is important that board members and faculty understand what appropriate contacts are—and what they are not.

- Inappropriate requests from faculty members (for example, lobbying a board member for their own interests or program) must be politely—but firmly— rebuffed.

- It is vital for board members to see themselves as champions for the entire institution—not any one part of it, or any individual.

- Boards (and presidents) should be proactive in creating forums and formats for board/faculty interaction.

- Shared governance is not shared decision-making.

- Shared governance at its best listens to the voices of the campus stakeholders and takes them seriously, but it does not give them veto power.

- Faculty, staff, and students should legitimately feel that their voices were heard in the deliberations that lead to decisions that affect them.

- It is important to communicate, to be as transparent as possible, so that the campus community isn’t surprised when a decision is made.

Organizational culture is in many ways more important than structure

- An institution can have a “perfect” shared governance structure, but it is unlikely to function effectively if it doesn’t meet the “threshold conditions.”[4]

- At the same time, a healthy culture of trust, collaboration, and transparency can often transcend imperfections in structure and policy.

- Building that culture is grounded in the need to develop mutual trust and respect among the partners in shared governance.

- Developing a culture that supports effective shared governance must be intentional—it doesn’t just happen.

- It’s important for boards and presidents to be as transparent as possible—and appropriate.

- Communicate—in both directions; people need to know that their voices are heard and valued.

- Ultimately, campus stakeholders must be able to see that the leadership—both board and president—are doing what they said they were going to do.

Thank you to AGB Mission Partner RNL for its support of this council.

David Maxwell, PhD is an AGB senior consultant and senior fellow and a coambassador for the Council of Board Chairs. He is president emeritus of Drake University and a trustee at Grinnell College.

1 For a discussion of this paradigm, see Johansen, Bob: Leaders Make the Future: Ten New Leadership Skills for an Uncertain World. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler Publishers, 2012.

2 For a sample decision matrix, see Bahls, Steven C.: Shared Governance in Times of Change: A Practical Guide for Universities and Colleges. Washington, DC: AGB Press, 2014, p. 87

3 In AGB’s white paper Shared Governance: Is OK Good Enough? (2016), only about 30% of the respondent presidents indicated that “a typical board member understands the work and responsibilities of the faculty well or very well.” (p.9)

4 See AGB’s white paper Shared Governance: Changing with the Times, p. 12 for a list of “threshold conditions.”

RELATED RESOURCES

Reports and Statements

Shared Governance: Is OK Good Enough?

Trusteeship Magazine Article

On My Agenda: Prioritizing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion and Shared Governance