- Assessments can help boards, committees, and members examine the leadership pipeline for succession planning by identifying the talents, skills, and backgrounds needed in its composition for consequential governance.

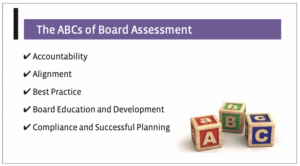

- Board assessments are essential to effective governance and exemplary trusteeship. They help boards focus on what matters most.

- By establishing a thorough assessment process and clear action plans to address the results, boards hold themselves and their chief executives accountable, demonstrate commitment to serve their foundations, and promote stronger board and executive performance.

A new board chair soon will take the helm. A new institutional partner has been appointed. New relationships and economic opportunities are emerging. A major campaign is on the horizon. The board wants to adopt a new strategic plan. These are just a few reasons why foundation boards consider undertaking assessments.

“Boards must hold themselves accountable for their own performance by modeling the same behaviors and performance they expect from others in their institutions. To do so means setting goals for board performance and benchmarks for measuring board effectiveness, as well as conducting regular board self-assessments.” This statement from the National Commission on College and University Board Governance, Consequential Boards: Adding Value Where It Matters Most, published by AGB in 2014, remains the clarion call even many years later. Board assessments, like regular wellness checkups, are essential for effective foundation boards to align with their institutional partners and remain accountable to their donors and other constituents. Individual, committee, and comprehensive board assessments deliver indicators for consequential foundation board governance. Foundation boards that can attest to their willingness to engage in self-reflective continuous improvement often find themselves more invigorated and purposeful in meeting their philanthropic missions.

Imagine the opportunities for strengthening your board’s capacity to govern more effectively before undertaking a strategic plan, a leadership change, or a major campaign. Even publicly traded companies are required by NASDAQ to assess themselves. Regular informal and more comprehensive assessments offer individuals and entire boards insights not often discussed during the regular course of foundation board meetings. “The members of institutionally related foundation boards can benefit from an assessment process that clarifies the relationship between the foundation and the university, as well as the respective roles of the foundation board, the foundation and chief executive, and the university administration,” according to Marla J. Bobowick and Merrill J. Schwartz, PhD, coauthors of Assessing Board Performance: A Practical Guide for College, University, System, and Foundation Boards (AGB 2018).

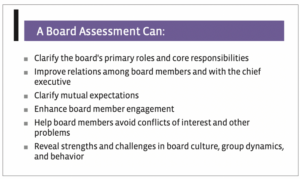

Further, as Charlene K. Reed, PhD, noted in The Role of the Board Professional (AGB 2017), “High-performing boards commit to regular self-assessment, both of the group and of individual board members. A board assessment can be extremely beneficial, as it:

- Enables the board collectively and trustees individually to reflect on their performance and effectiveness;

- Identifies issues and questions that need to be addressed;

- Ensures that outcomes drive an action-able plan for board improvement; and

- Demonstrates the board’s commitment to evaluation as an organizational value.

For Georgia State University Foundation’s board, delving into a comprehensive assessment gave them an opportunity to prepare for their future and that of the university it supports. Kevin Lofton, currently the vice chair of the GSUF board, previously served as a member of their governance committee and led the assessment task force that led the more than 30-member board through the comprehensive process. He said, “It is best practice for a board to take a comprehensive look at itself to improve governance effectiveness and efficiency. The GSUF was a critical point of change. The world was in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, the university had just hired our new vice president for Institutional Advancement, and a search was underway for a new university president. It was the perfect time for the board to focus on improving how we operated, as well as focus on growth, our wants, and desires.”

For foundation boards, an assessment can be as straightforward as looking back at the end of each year and asking the question, “How did we do?” to more extensive approaches such as a comprehensive assessment that often occurs in five-year cycles. Taken as a standard governance practice, assessments help new board members and longer-term members understand their roles and responsibilities more clearly.

James Lanier, an AGB senior consultant and senior fellow, encourages boards to delve into these considerations, “During assessments, board members can ask themselves a series of questions such as:

“What are the standards that we need to hold ourselves to? It’s a time to refresh and renew your look at our policies and procedures. Are we following them? Looking at the governing documents, and you bylaws, are we running the board as we are supposed to do it? Are we voting correctly? Are we doing the kinds of things we need to do for good governance?”

Recently, the University of Toledo Foundation made the decision to better understand its policies, practices, and procedures that could lead them to become a more consequential board. The foundation’s president, Brenda Lee, explained why this approach was taken. “With almost half of our trustees being appointed within the last three years, it provided an opportunity to engage them in a deep and meaningful way that sometimes doesn’t happen until later in a trustee’s tenure. The effort will hopefully serve as the foundation for a positive trustee experience during their time on the board, as well as translate into more support for the university. In addition, the assessment laid the groundwork for our strategic planning efforts, which will begin in the spring, following the completion of the University’s strategic plan.”

Assessments are at the very core of the Principles of Trusteeship (AGB 2021, see graphic further below) that require board members to:

- Understand Governance

- Lead by Example

- Think Strategically

Individual board members and the board as a whole can be more effective when all three areas are achieved.

Individual Board Assessments

Individual board member assessments should never come as a surprise. When new members join the board, a statement of responsibility or expectations should be prepared and presented for discussion and signature. Likewise, as with any performance evaluation, the assessment of individual board members should be based on expectations that have been agreed upon in advance.

Once board members know specifically what is expected of them, it becomes easier to assess whether they are meeting those expectations. Other means of individual self-assessment may include:

- Self-reflection to discover alignment with the nine primary tenets outlined in Principles of Trusteeship;

- Examination of participation/attendance records;

- Interviews and conversations with the committee on trustees/governance committee and/or board chair; and

- Exit interviews with the board chair and president.

To be effective, individual board member evaluations must be confidential and provide opportunities for members to evaluate their own performance against the board’s statement of expectations, as well as to raise questions or concerns. The governance committee should digest the results of individual board members’ self-evaluations, make recommendations about actions on board members’ status as needed, and share any other relevant conclusions with the full board as appropriate.

Such individual assessments are particularly useful when a board member’s term is about to end and the individual is being considered for reelection. As the governance committee prepares for an upcoming election, it should ask incumbents who are eligible to complete a self-assessment before having their name added to the slate.

A self-assessment and a subsequent conversation with the board chair also:

- Assist incumbents in considering whether they will stand for reelection;

- Reminds them of their responsibilities if they were to be elected for an additional term; and

- Helps the governance committee determine whether to nominate a member for an additional term.

Such topics as attendance, service as an ambassador, knowledge of and understanding the mission of the foundation and its partner institution, philanthropic priorities, roles in fundraising, the financial health of the foundation and the partner institution, and relationships with administrators also are reviewed during individual assessments.

Board Committee Assessments

Foundation boards of the future must focus more on strategic philanthropic issues that align with their partner institutions. So, while individual trustee assessments are underway, board committees often take a hard look at themselves by taking an inward, reflective journey to determine whether they are focused on the “right” work to support their philanthropic endeavors. Some board committees even emerge from the assessment process with new infrastructure or refreshed and more meaningful charters for their work. By taking a hard look at the work of committees, many find engagement during their meetings to be more focused, meaningful, and constructive.

Many of the boards AGB studied, as noted in the 2015 AGB report “Restructuring Board Committees: How to Effectively Create Change,“ began with a thoughtful assessment of their current structure, including the number and focus/charters of their committees, committee meeting schedules, and the size of the board. As a result, they were able to identify what they believed to be the barriers to effective governance and full board engagement. At the root of the problem for many boards was a series of challenges, ranging from board composition to board procedures.

Two of the most common issues to emerge from many boards’ assessments of their committee structures were board size and the number of board committees. Several boards reported being too large to work effectively or having too many committees. In both circumstances, the number of people and committees made it difficult to prioritize and address the most salient strategic issues. Boards that are either too large or too small can be under-engaged or stretched too thin to do important work.

By assessing how the board’s size and the number of its committees influence one another, several institutions were able to downsize their boards and identify the right number of committees to address the needs of their foundations successfully. Committee assessments have another benefit. Many boards have little cross-fertilization among their different committees. But a board can extract more value from committees when it explores comparative data to determine why some committees perform better than others so that good practices can be shared. In many cases, intentional collaboration and synergy among committees emerge after such an evaluation, which leads to greater impact and effectiveness.

In their book Governance as Leadership: Reframing the Work of Nonprofit Boards (Wiley 2004) Richard Chait, PhD, William P. Ryan, and Barbara E. Taylor have offered key questions committees should consider:

- How would you summarize the central purpose of this committee?

- What was the most strategically significant work this committee did in the past year?

- What is the most strategically significant work this committee should do in the year ahead?

- What would be lost to the organization if this committee did not function for two years?

- What have you enjoyed most about serving on this committee?

- What have you least enjoyed about serving on this committee?

- What could the chair of this committee do to make the committee more effective?

- What is the most important thing you have learned from serving on this committee?

Comprehensive Board Assessments

Boards should hold themselves accountable for fulfilling their fiduciary responsibilities. An assessment provides a process for the board and chief executive to make their goals and expectations explicit and for aligning their work to meet those ends. A thoughtful process can inform the board of best practices in governance and be a forum for educating and developing its members.

Assessments can help boards examine the leadership pipeline for board officers and identify the talents, skills, and backgrounds needed in their composition. Being a high-performing board takes an ongoing commitment to a virtuous cycle of learning and reflection—to look at why, what, and how the board does what it does. It’s a cycle of setting goals, assessing performance, and using feedback to improve.

GSUF’s Kevin Lofton noted the process helped the board address its effectiveness, “The assessment allowed the board to understand our current state and chart a course to improve our effectiveness. The process included receiving input from a comprehensive list of stakeholders and resulted in our developing a long list of things we wanted. We subsequently prioritized the list into five focus areas. The board successfully implemented work plans to accomplish or make progress in every area. The board regularly refers to the plan.”

The basic goal of a board assessment should be to improve performance. At its best, such an assessment educates board members about their responsibilities and clarifies boundaries between the board and administration. It builds a shared understanding of the respective roles of the board, chief executive, cabinet members, and others. It can help identify ways to use board members more fully, in ways they prefer, and increase appropriate member engagement. It can educate members about practices and policies and help them avoid conflicts. And it can identify and address problems in how board members understand their roles, how they communicate with one another, and how they interact with the foundation community.

The Kent State University Foundation undertook a comprehensive board assessment several years ago and the experience prepared its leaders and executives to lay the groundwork for the future. “The board assessment process was an opportunity to take a great board and make it even better,” said Scott McKinney, Kent State’s associate vice president for donor and volunteer engagement and COO for the KSU Foundation. “The assessment allowed us to pause and reflect on all our governance processes and have discussions around industry best practices. The discussions that took place within the context of the assessment have continued and have led to some meaningful changes. For example, we are in the process of launching our Legacy Member Program–designed to keep former members engaged in the way that best suits them.”

Assessments also can set the sights of the board to focus on what matters most and to work at a more strategic level. A thorough assessment can identify any barriers to success—such as those mentioned previously including committee structures, trustee responsibilities/accountabilities, and meeting agendas—so the board can concentrate on what’s important. It can uncover what’s missing or getting in the way of better board performance—such as composition, policies, skills, and knowledge.

The best board assessments are results oriented. Not only do they include consideration of the current performance of the full board, but they also serve as the bedrock for an action plan that will guide the work of the board, its committees, and the administration for the succeeding years.

Planned and led effectively, the assessment process can enable a board to understand how a group of high-achieving individuals from various walks of life can come together and function as a team. The most persuasive and respected chief executives, board chairs, and board members may need help in motivating a board to higher levels of achievement. And through periodic reflection, even the members of a very effective board can renew and improve their personal and collective commitment to their institution.

“If a board is to truly fulfill its mission—to monitor performance, advise the CEO, and provide connections with a broader world—it must become a robust team, one whose members know how to ferret out the truth, challenge one another, and even have a good fight now and then.”—Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, “What Makes Great Boards Great?” Harvard Business Review (September 2002).

In “Assessing Board Performance” (AGB 2018) AGB encourages boards to follow several processes when undertaking a formal assessment to ensure the board assessment is conducted with objectivity, candor, and utility:

- Survey. At the heart of the assessment process is a confidential survey of the board. Individual responses are reported in aggregate and without attribution.

- Retreat. The board commits itself to a half- or full-day retreat to discuss the findings in an executive session with only board members and the chief executive.

- Facilitator. An outside consultant is hired to guide the process, analyze the results, and facilitate the retreat.

- Action plan. The board and facilitator develop a board action plan based on the results of the survey and retreat discussions. This plan will guide the work of the board and committees for the next two to three years.

In Effective Board Chairs: A Guide for University and College Chairs (AGB Press, 2016), Jeffrey B. Trammell, JD, writes of how board chairs are responsible for leading self-assessment processes for the full board and individual members. This responsibility often is transferred to the trusteeship or governance committee to lead the charge and identify external expertise to facilitate the processes and retreat.

Rae Mang, the chair of the University of Cincinnati Foundation Board, said, “Our board uses assessments in a couple of ways. We survey our board population probably a couple of times a year and we do it as an entire entity. And, certainly, with not being together these last several years, our survey frequency has gone up a bit, and we use surveys to inform the content for our board meetings. We use surveys when we want to make a change to governance. For example, reducing term limits from three four-year terms to three three-year terms. And, after each meeting concludes we ask how the experience was for them. How their time was utilized. Did they have opportunities to engage each other and university leaders? And we use that information to hopefully improve our meetings over time.”

In addition to assessing board meeting effectiveness, roles, and responsibilities, board assessments, especially for foundations dovetails into the critical role board culture plays in building and strengthening relationships within the board itself and with its external constituents.

We’ve all heard the saying “Culture eats structure for lunch.” Through an assessment of the board as a whole, better information sharing and agreement on strategies and the institution’s direction will emerge. Boards are social systems designed to advance the mission of the institutions they serve and other important initiatives—campaigns, strategic plans, scholarships, economic development programs, and other high-level goals. Jim Lanier stresses that a board’s culture—”those unwritten rules and processes that come into a board over time” play a key role in whether or not that board becomes highly effective and consequential.”

“When we talk about the best results and transformation of boards, sometimes I’ll have a member who’s been on the board for a number of years, say ‘Remind me exactly what I’m supposed to do.’ Too often, we bring outstanding individual leaders onto boards, and we expect them to know exactly what to do, but we don’t spend the time and continuing education to help them to look at the key elements of governance. Many excellent volunteers come in knowing that, but you would be surprised that many do not understand the obligations and responsibilities that they have as members. Most boards come out of assessments having a firmer understanding of what it is they have as

priorities of the board, what individual priorities they have as members, and have the feeling there is a roadmap going forward.”

Board Assessment Surveys and How to Conduct Them

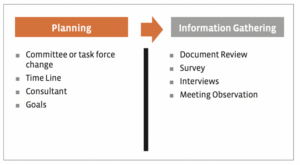

The process of assessment involves:

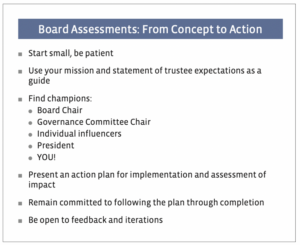

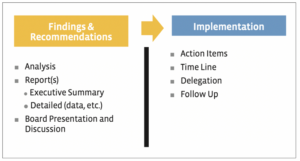

1) planning, 2) information gathering, 3) findings and recommendations, and 4) implementation.

According to Assessing Board Performance, best practice illustrates that “the best time to schedule a board assessment is when no serious programs or issues are at hand, so the review does not appear punitive or targeted toward ousting troublesome board members. To this end, the board may want to establish a policy and procedure for regularly conducting a board assessment. Boards of public institutions will need to ensure their actions are consistent with applicable laws regarding open meetings and records.”

Typically, the governance committee and executive committee members take the lead in planning by assigning members to serve on a special committee or task force to develop the time line, review the assessment questions, work with a third-party consultant, and recommend goals for the assessment process and retreat. For foundations with limited resources, internal institutional research experts potentially can help design reliable and verifiable survey instruments.

Working together with the third-party consultant, the task force or committee validates impressions from the survey (and interviews, if included in the assessment process). Supporting this task force is the full board, which commits to offer candor, involvement, and full participation in the process. The planning team strives throughout to help the board realize its most important goals for the assessment.

Additional resources used during the board assessment include recent accreditation reports, meeting agendas and minutes, charters, annual reports, recent campaign materials, governing documents like bylaws and other legal documents, institutional trend data and dashboards, and strategic plans. In addition, interviews with people who have close ties to the board—for example, the chief financial officer, general counsel, other executive leaders, and the board professional—offer additional perspectives and valuable points of view. Many boards also include influential emeriti members who may recently have completed their terms yet have invaluable knowledge and wisdom to share.

The final phases of a comprehensive assessment are when the real work begins. Typically, an executive summary and detailed report are generated and shared with the board chair, chief executive officer, and task force/committee members. The full board then receives the final results during its retreat, where the transition from “findings and recommendations” to “implementation and action” occurs. The assessment results become teaching tools and suggest new ways of operating, including the development of appropriate standards, practices, and benchmarks.

Typically, no more than three or four action items should emerge as important to address over the course of the next three to five years. The task force or committee is responsible for bringing structure and clarity to the outcomes, so the board continues to address the key findings and true change occurs. Most boards that participate in an assessment process ensure that progress updates on the findings and action plan remain on the board’s standing agenda for the foreseeable future.

For the University of Toledo Foundation, choosing AGB to lead their assessment offered more than they expected. “Use an AGB consultant to facilitate the process. You will get so much more out of the process if it is facilitated by an AGB consultant than if the assessment is staff-led. I was surprised by the amount of work that went into the assessment, mostly done by the consultant, prior to actually having our day-long retreat. It was well worth the investment. I can say that the experience exceeded both my expectations and the expectations of our trustees,” said President Lee. The foundation soon will begin a strategic plan in partnership with AGB.

Several board assessment options (Basic, Classic, Premium) tailored to the needs of available resources ranging from complimentary member-exclusive self-assessment tools to more comprehensive facilitator-led processes that include written surveys, interviews, and in-person facilitated retreats are available through AGB. Components of these assessments range from self-service online questionnaires to AGB’s facilitated board retreats complete with comprehensive and detailed analysis and recommendations to the board. For more information visit: https://agb.org/agb-consulting/board-assessment/

Lynnette M. Heard is an AGB senior fellow and senior consultant in the areas of board assessments, board and leadership development, board selection and composition strategies, diversity/equity/inclusion strategies, bylaws review, parliamentary procedure, and public and media relations. In addition, she leads the Board Professionals Certificate Program Task Force and serves as the ambassador for AGB’s Council of Board Professionals.