- Internationalization can take the form of marketing to international students, partnerships with companies and other universities, study abroad programs, or a host of other relationships. Along with greater opportunity, internationalization exposes your institution to greater risk, which has to be measured and managed.

- Many institutions are experimenting with technology for international learning, either by itself or in combination with conventional study abroad. Trustees can help ensure that study abroad is a means to the end of international learning and not an end in itself.

- Assess the institution’s international expertise and capacity. This effort should focus on existing faculty and programs, but it should also include board members, staff, alumni, and donors.

- An international plan that is developed and owned by the entire stakeholder community will ensure that a single campus office is at the center of global engagement, while breaking down silos and creating a sense of urgency.

- Effectively communicating your institutional strengths to potential students outside the United States will require a fresh marketing approach.

- Ensure that expectations for growth in international enrollments include a parallel commitment of resources to serve those students. A useful number for your dashboard is the ratio of international student tuition revenue to dedicated expenses for student support.

- Multiple student perspectives, driven by different cultural assumptions and values, contribute to deeper learning for everyone.

The pandemic has put tremendous financial pressure on colleges and universities, leading them to examine their value proposition and reassess their business model. Sticking to the basics and riding out the storm seem to be the norm at many institutions. In the midst of these challenges, the international activities on your campus may seem like a secondary issue, or even a distraction. It may seem contrarian, but by the end of this article you will see that internationalization is part of the solution: It will sharpen your brand, advance your mission, and strengthen your finances–if you do it the right way. This article will guide you through that process.

First, a jargon-free definition: Internationalization is the advancement of your institutional mission through the pursuit of opportunities outside the United States. It can take the form of marketing to international students, partnerships with companies and other universities, study abroad programs, or a host of other relationships. Along with greater opportunity, internationalization exposes your institution to greater risk, which has to be measured and managed.

This definition of internationalization will serve as the backbone of a written international plan, which will build on but remain separate from your institutional strategic plan. You may still be exhausted from a previous planning effort, or you may be so focused on putting out fires that long-term planning on any issue seems unrealistic. But a dedicated international plan is critical. It can go into much greater depth than your strategic plan, with clearer goals, time lines, and resource commitments. A separate international plan also offers the opportunity to undergo a scan of your international resources and capacities, which will generate a list of promising opportunities for your institution.

There is no established structure for an international plan, but it should have the following six parts:

International goals, developed through a process of broad consultation with key stakeholders, including the board of trustees. The entire institution and its supporting communities should feel a sense of ownership, and the document should not be associated with any individuals—including board members, senior faculty, and executives.

A board discussion about international planning should initially focus on these questions:

What is the international content in our current strategic plan? Has anyone been assigned responsibility for execution?

What are our current international activities, and what are their implied goals, even if they have never been articulated? Do they advance our mission as an institution? What information would we want to gather from a deeper institutional scan?

If we were presented with a major international opportunity, how would we responsibly evaluate its potential risks and benefits?

How would our community respond to a major planning effort that focuses on internationalization? Are we still “recovering” from a

recent planning experience? Would a new planning effort energize our community or be met with resistance? Do we need an external advisor or consultant to help us design and execute the planning process?

International learning goals for every student. The curriculum is sacred territory for faculty, and boards should tread carefully here, but you have several important roles. First, you can ensure that the curriculum is developed through consultation with external stakeholders, including employers and alumni. Faculty may have the final say, but board members can ensure that other voices are included in the discussion. Second, boards can help to build a culture that recognizes and supports the value of measuring student learning. Many board members will have helped to build an assessment culture in their own organizations, and their perspective can be particularly effective. Board members should also hold the senior leadership accountable for linking the curriculum to the value proposition and brand identity. The strategic plan should define the knowledge and skills that every graduate will possess when they leave the institution. If your value proposition states that every graduate will have a global perspective, then you should ask how that is being accomplished.

Keeping all this in mind, these are some of the learning goals that typically appear in international plans. As you read through these, think about how your recommendations and guidance could support their delivery at your institution:

- Knowledge of global challenges and potential solutions;

- The ability to complete tasks in an international environment, such as working on a team with members from different countries;

- An understanding of your own cultural biases and limitations;

- Fluency in a foreign language;

- Deep knowledge of a particular country or region that has importance to the United States; and

- An understanding of the design and operation of global institutions.

Most institutions have study abroad programs, which can be critical for advancing international learning. But these opportunities are not available to many students, even when the institution makes an effort to increase access through financial aid and scheduling. The board can help to keep the focus on international learning goals, which can often be reached without leaving the home campus. The pandemic has greatly increased our comfort level with the use of technology for communication and collaboration, and many institutions are experimenting with this technology for international learning, either by itself or in combination with conventional study abroad. The key is to ensure that study abroad is a means to the end of international learning and not an end in itself.

A survey and analysis of international expertise and capacity. This effort should focus on existing faculty and programs, but it should also include board members, staff, alumni, and donors. This is where dedicated international planning is essential, since most strategic plans do not take this finely grained approach. Additional investments in faculty, either in the form of new hiring or professional development, should address the gaps between existing capabilities and your articulated international goals. But there are other benefits. One is uncovering international connections, activities, and capacity that you never knew existed. Another is the spontaneous generation of ideas for new programs, partnerships, and revenue generation.

A comprehensive plan for international students. International students are the main source of new revenue in any internationalization plan, and this is the most important international goal at many institutions. I have dedicated a section on this issue below.

A structure for managing international partnerships. Most colleges and universities are divided into silos, and this is especially true of external partnerships: Employers, donors, learning partners, vendors, and government regulators are each managed independently. When I worked in a business school, it was immensely challenging just to come up with a comprehensive list of corporate partners. These firms could be recruiters, donors, research partners, sponsors of student projects, or major contributors to executive education programs, and they often filled several roles at the same time. A separate office managed each aspect of the relationship. Even within the office of development, which ideally has a bird’s-eye view of external partnerships, turf issues abound. I once led an alumni tour during which I was provided with a list of everyone who donated to the alumni association, but not the much more important list of major donors because the list was managed by a different office.

Somehow, this absurdity seems more obvious in an international context. Imagine walking into a hotel lobby in London or Delhi and seeing a senior executive from your institution; You are both there on university business and neither of you knew about the other. Or perhaps you have a student exchange program in Mexico and are unaware that your most important corporate recruiter has major operations there—operations that could be sponsoring internships or research projects.

Board members can take a principled position on this issue without getting into the weeds. At a minimum, a single campus office should manage all international academic partnerships as well as those with multinational corporations, foreign governments, and international nongovernmental organizations. Ideally, the same office should be able to access information on international donors, alumni, and marketing strategy. An international plan that is developed and owned by the entire stakeholder community will ensure that this office is at the center of global engagement, while breaking down silos and creating a sense of urgency.

An organizational structure that supports international goals and objectives. A common outcome of international planning

is the creation of an executive position that will take the lead on internationalization, which can send a powerful message of strategic intent. A commonly used term for this position is senior international officer (SIO), but in practice there are many titles.

Here is another strong argument for creating a dedicated international plan. When these plans are done the right way, with broad consultation and consensus building, the entire institution— including the board—owns the international goals. This gives the SIO strong momentum when it comes time to implement the international plan. It also gives the board the right and the responsibility to ask the tough questions about implementation, accountability, and organizational change. When it comes to the creation of the SIO position, here are just a few of the critical issues:

What should be included in the SIO portfolio? It may be tempting to charge the SIO with internationalizing the curriculum, but this territory is likely to be crowded with entrenched interests. Charging the SIO with meeting unrealistic goals can undercut their credibility in other areas. At many institutions, the provost or president will be in a better position to lead a comprehensive review of the curriculum, including but not limited to international content.

How will the SIO be held accountable? This starts with ambitious but clear and realistic international goals for the institution as defined by the international plan. When the entire community feels ownership of international goals, then they will also expect to be updated on progress. The board should devote time to designing (or updating) a dashboard that measures the key performance indicators in the international plan.

Will the SIO have the support to deliver on international goals? Beyond the obvious questions about funding and staffing, the board should ask about the level of support from the rest of the senior executive team. A typical restructuring will place study abroad, international student services, and international partnerships in the SIO portfolio, but in my own experience, the invisible lines of the org chart are at least as important. What if the records for international alumni need a major overhaul? What if a new study abroad destination requires a redesign of the risk management function? What if an international visitor needs basketball tickets? All of these involve reaching across the organization into other silos. A diplomatic and tactful SIO will be essential, but just as important will be a strong signal that the work of the SIO is central to the mission of the institution.

Building an International Brand

No doubt your strategic plan includes a passage that states the value proposition for attending your institution. If you participated in the development of your most recent strategic plan, you may still have painful memories of the difficult trade-offs and compromises that led to the final version. The result should be a clear and compelling argument that carves out a distinct competitive niche for your institution. This would be a good time to reread this part of your strategic plan if you haven’t done so recently.

The lessons from the private sector are relevant here. Seven of the ten top brands in the world are owned by U.S.-based firms, including Apple, Google, and Amazon. All of these companies started with a focus on the domestic market in the United States, developing products that were designed to meet the needs of U.S. customers. And yet all of these firms became very successful internationally, and they did it without major adaptations of their products. Foreign customers enthusiastically purchased their products because the value proposition was so compelling that they were willing to adapt themselves to the product instead of the other way around. In management lingo, we call these international firms because their products were developed initially for their home market and then crossed national borders. Other firms are global because they try to develop products that will appeal to a worldwide audience from the start. A good example is the Hollywood blockbuster with plenty of action and a relatively simple plot and dialogue. Among the top ten global brands, all are owned by international firms.

Look again at your strategic plan and the articulated strengths of your institution. It is likely that your value proposition for domestic students will also be compelling for international students—in other words, that you should take the international approach rather than the global one. Take, for example, the common assertion that the institution develops leaders in a variety of fields, including future executives, social entrepreneurs, or artists who will redefine their genre. The same value proposition will work in many international markets, including the most important ones. Another message that crosses international borders effectively is the assertion that students will learn to think analytically and creatively, which could be an end in itself or a means to a successful career.

That’s the good news. Effectively communicating your institutional strengths to potential students outside the United States will require a fresh marketing approach. Think back to the private sector examples: These firms entered international markets without adapting their products, but their marketing still had to be adapted to local cultures and tastes, and they had to take different marketing channels into account. In the case of higher education, studying in the United States will very likely be the most expensive option for students, so messaging has to be much more than just marginally compelling.

Below I present a quick tour of the three key markets for international students. As you read through the descriptions, think about your core value proposition and how it would address the needs of students in these countries.

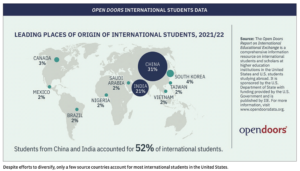

China

This is the most important market for the United States, with more than 300,000 students currently enrolled in American institutions. The vast majority pay for their education through private savings, and family capacity to pay out of pocket is increasing rapidly. The vast majority of high school students take a national examination that will determine their placement in a Chinese university; those with top scores will be placed in world-class universities like Tsinghua or Fudan. These students may choose to study in China even if they could also attend a top university in the United States. Those in the next tier will also be placed in a Chinese university, but not a top one, and they are prime candidates for study in other countries. There is a vast network of agents and advisors who are ready to help families with the application process; many are honest but a significant number overpromise or cut ethical corners. An important driver of this business is the application for admission, which can be bewildering to families who are familiar only with the national examination. Equally intimidating is the fact that there are more than 4,000 higher education institutions in the United States.

The motivations for studying in the United States have evolved over time. Initially, most Chinese students were graduate students in science and engineering, but many are now pursuing degrees in business and other professions. For this group, a prime motivator has been the possibility of working in the United States after graduation, initially with an extension of their student visa and ultimately with the hope of remaining for the longer term. With growing professional opportunities in China, especially in the private sector, more Chinese graduates are returning to China for work. For better or worse, Chinese families pay close attention to national rankings, but there is a growing realization that the United States boasts many quality institutions.

A large percentage of Chinese students have parents with college degrees who have either studied outside of China or currently have careers with high international content. This increased sophistication has led to skepticism about the quality of Chinese higher education—and especially its notorious emphasis on rote learning and memorization. This has led to an increased appreciation for teaching quality. The liberal arts model, with an emphasis on critical thinking, oral and written communication, and the acceptance of more than one correct answer to a complex problem, is particularly appealing to these families. Partially for this reason, roughly half of all Chinese students in the United States are now undergraduates.

U.S.-China relations are at their lowest point since diplomatic relations were normalized more than 40 years ago, and there are growing signs that the strains are spilling over into higher education. For example, the U.S. government is denying visas to student applicants with ties to the Chinese military. The numbers are modest, but the policy has infuriated many other applicants, leading them to look at destinations other than the United States. China continues to be the target of other proposals, including a nascent movement to persuade universities to divest from Chinese firms.

India

India is the second largest source country for the United States. With all the concerns about China’s economic rise, it’s easy to miss the fact that India is also growing rapidly, with families willing to use their rising incomes to pay for education at all levels, from primary school through college. There are excellent universities in India, but their capacity is extremely limited compared to the vast population. There is a widespread perception that U.S. higher education is much better overall, which is reinforced by the large number of people in India who have already studied in the United States. Many have remained to live and work, forming a network that can help with careers and employment. English is widely spoken in India.

Indian students highly value the possibility of remaining in the United States after graduation. There are a number of legal pathways for achieving this, but the policies and statements of the Trump administration have led many people in India to believe that immigrants are not welcome in the United States. The media in India also focus on crime and gun violence, contributing to a sense that the United States is more dangerous than alternatives like Canada or the United Kingdom. You can expect Indian students to carefully weigh the costs of attendance against starting salaries and the potential for professional advancement. This single-minded focus on the economic gains of a university education can be an opportunity for institutions that can demonstrate they are a good value, even if they are not well known or highly ranked.

Anecdotally, employers in global technology industries say that Indian students have excellent technical training but may lack the ability to take creative approaches to solving problems. Even a task that seems narrow and well-defined—such as writing computer code—can include obstacles that require fresh and innovative thinking. Institutions can emphasize their ability to develop these skills, even in technical fields like engineering. Alumni—ideally Indian nationals with successful technology careers—can be mobilized to reinforce this point.

Saudi Arabia

Demand for study in the United States is driven by massive government funding—at one point one-quarter of the country’s national budget. This support is generous: full tuition, international travel, and a living stipend. In some funding categories, institutions must be on an approved list that is based on institutional quality, but I have heard anecdotally that many Saudi students are not qualified for admission to these institutions. Managing your relationship with the Saudi government should be considered a fixed cost of being in this market.

Saudi Arabia’s national budget and the scholarship program are heavily dependent on oil revenue. (Next time you fill up, imagine your dollars recycling back into U.S. universities. I hope that helps.) The government cut the scholarship budget in 2016, when oil prices fell, although they recently set new, ambitious targets through 2030. There are geopolitical risks as well. When the Canadian government criticized Saudi Arabia’s human rights record, the response was to cancel all student scholarships at Canadian universities, setting off a hectic rush to find transfer schools in the United States. In another case, a number of U.S. institutions called for cutting ties to Saudi Arabia after the assassination of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi by agents of the Saudi government.

This is a country that is tech savvy—there are more smart phones than people—and a marketing campaign should focus on social media and other tech platforms. What Saudi students don’t care about is staying in the United States since their scholarships require them to return home after graduation. Any value proposition that is based on the quality of teaching should emphasize student support, including academic tutoring, advising, and English language courses. Like all international markets, academic rankings matter, no matter how flawed the methodology.

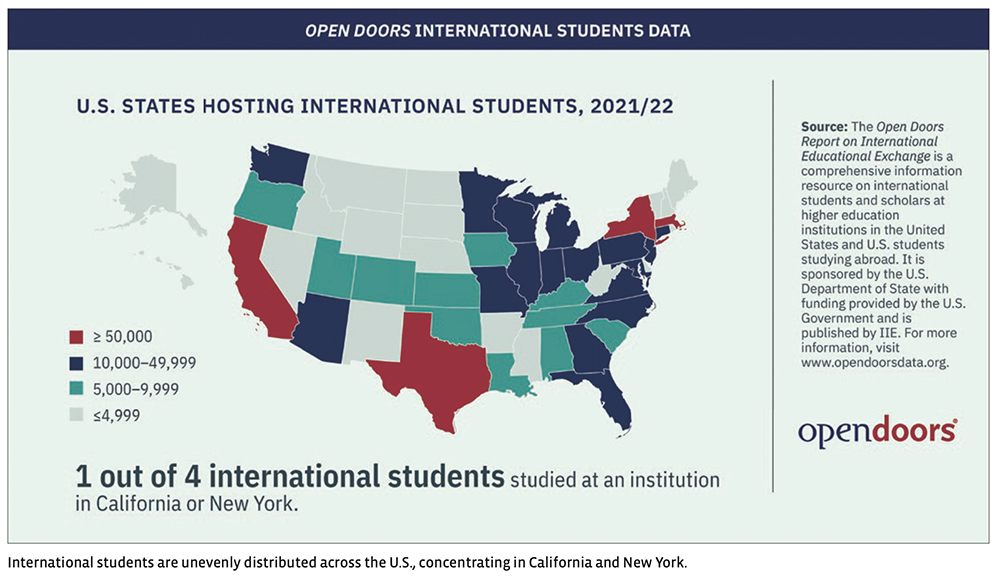

Managing Risk as well as Reward

Half of all international students in the United States come from China and India. Diversification has been the Holy Grail of international education for decades, but the results have been disappointing. Developing a marketing infrastructure in a new country takes years of investment, and many institutions do not have the resources or the patience to pursue such an effort. The high price tag for U.S. higher education means that smaller countries will have only a limited number of students who can afford to come to the United States. Finally, the U.S. government frequently denies student visas to applicants from developing countries, arguing that they are at risk of remaining in the United States illegally after graduation.

Imagine a board meeting during which you are looking at your latest enrollment numbers, and they are concerning. Perhaps domestic enrollments are down, and a board member wants to talk about recruiting internationally. Maybe you already have an international marketing plan, but the actual numbers are not meeting their target. Or you might have a sizable number of international students already, but the numbers have been declining. These are the questions to guide your discussion:

- What is our value proposition to international students? Is it distinctive, clear, and backed by evidence and examples?

- Does our international plan make a resource commitment to marketing our institution? Who is accountable, and are they getting the resources they need?

- Do we understand that some marketing efforts could take years to pay off?

- How do we prioritize national markets?

- Do we need help? Where are internal resources lacking, and do we hire more staff or purchase services from an outside vendor?

The last bullet is worth exploring, especially if your institution has a policy that requires large vendor contracts to be approved by the board. International education is replete with firms that can help you design and execute a marketing plan, recruit students, and even deliver instruction. It is a very different world from domestic marketing. Just to take one example, recruiting agents in foreign countries are allowed to charge a commission to the U.S. institution, while other agents may charge fees to the student and their families.

Another model, known as a pathway program, focuses on recruiting students who would not otherwise meet the admissions criteria set by the institution. Instead, the pathway provider offers special classes during the first year that focus on improving language and academic skills. The student is then mainstreamed in their second year. Contracts with pathway providers are complex and they can be controversial since they outsource one of the core functions of the institution. When I gave a presentation at the AGB annual meeting a few years ago, a board member told me that a pathways agreement was placed on their agenda because of the size of the contract. The board was not even aware that these discussions were taking place, and since they were not receiving regular updates on international strategy, they had no context for evaluating the agreement. The result was an awkward meeting and a delay in approving the contract. A written international plan with clear goals and resource commitments would have provided the proper framework for making such an important decision.

Supporting International Students

With revenue generation a top priority for many institutions, it is easy to overlook the fact that international students also have special needs that use resources. In many cases they can use the same services that are offered to domestic students, but as international enrollments grow, you can expect to see budget requests that create tailored services. One emerging issue is mental health: While incidents of mental illness are rising rapidly among all students, the problem is especially acute for international students. They are often under tremendous pressure from their families to excel academically, they are living in a foreign country and culture, and their own cultural norms can make it difficult to seek help. Another area is career advising: International students are unable to take advantage of the employment opportunities that are open to domestic students because of legal restrictions on their visas. There are exceptions that allow firms to employ international students for limited periods immediately after graduation but finding and attracting those firms requires a special effort. If you see growth in international enrollments without a parallel commitment of resources to serve those students, then you should be raising the alarm during budget meetings. A useful number for your dashboard is the ratio of international student tuition revenue to dedicated expenses for student support.

The classroom is faculty turf, but I will argue for one exception here. Many faculty do a poor job of involving international students in the classroom, especially when it comes to highly interactive work such as case analyses, oral presentations, and the discussion of readings. International students may highly value these experiences but lack the language skills and cultural cues that are essential for being active participants. A modest investment in faculty development can deliver outsized returns in international student satisfaction. Remember that the value proposition for your institution may be based on the quality of classroom instruction or the development of communication skills. Investments in improving classroom dynamics can also deliver benefits to domestic students. An international perspective can contribute to a deeper understanding of many subjects, including those that appear to have no international content. My spouse teaches a course on the use of color to students who are studying industrial design, and many of her students are from outside the United States. Multiple student perspectives, driven by different cultural assumptions and values, contribute to deeper learning for everyone.

Finally, be sure your international plan includes exit surveys that are designed to measure student satisfaction. These numbers should also appear on your dashboard. The surveys should identify strengths that should be advertised and weaknesses that should be addressed. Be prepared to be surprised: Those quiet students who never complain may have a lot to say when their comments are confidential.

Making the Case to Your Stakeholders

Many Americans are already skeptical about the value of higher education. Not surprisingly, they are also likely to be skeptical about the benefits of internationalization, especially if the arguments focus on the benefits to the institution and not the larger community. Board members and senior executives should be prepared to defend their international activities with evidence-based arguments that demonstrate the value of internationalization to all stakeholders. Here are four key arguments.

Internationalized institutions are stronger. Institutions often charge full tuition to international students (and nonresident tuition in the case of public universities) and may even charge them additional fees for some services. Although the presence of international students requires additional staffing, it is very rare to find a campus that is not experiencing a net financial gain.

Moreover, these same students eventually become alumni who may become donors to the institution and open doors to more international opportunities. Institutions can also generate revenue through research grants and contracts that have an international focus. Many institutions also have the capacity to provide training and professional development to foreign nationals, with funding through grants or by directly charging instructional fees.

International activities can also improve institutional rankings. Some rankings explicitly identify international activities as part of their methodology, including study abroad, international student enrollments, and international content in the curriculum. International activities can also indirectly affect rankings through higher standardized test scores and higher levels of research funding. While most campus leaders and their boards have serious misgivings about the methodology, there is no denying that a strong showing contributes to the reputation and prestige of the institution.

Outside the question of rankings, most institutions noted for their excellence have a significant global footprint. Much like products and brands in the private sector, the international reputation of an institution builds on its domestic image and reputation. The process of leveraging domestic assets in order to create global opportunities will be readily understood by board members and other stakeholders who have a background in the private sector. Institutions may find themselves in a virtuous cycle during which a strong domestic reputation attracts prestigious international partners and donors, which in turn builds its domestic reputation.

International students are good for all students. The presence of international students in the United States can be a sensitive issue. Public concern generally falls into one or more of these areas: (1) that international students take seats away from domestic students, (2) that they stay in the United States after graduation and take jobs from U.S. citizens, and (3) that they pose a national security risk. Nevertheless, the economic impact is clear: NAFSA (the Association of International Educators) estimates that each international student in the United States spends $31,000 annually on tuition, housing, and other services.

For the many public and private institutions that are struggling to meet their enrollment targets, they can easily accommodate both domestic and international students. As for immigration, international students can only enroll in a U.S. institution when they have been granted a visa that is restricted to this purpose. The visa laws of the United States clearly designate the student visa with a non-immigrant visa, without a pathway to permanent residency. By law, the burden of proof is on the student, and every year thousands of applicants are rejected before they leave their home country.

Finally, there is the growing sentiment within the federal government that colleges and universities are vulnerable to the loss of technology to other countries, especially China. Even the critics acknowledge that the vast majority of international students come to the United States in order to acquire knowledge legally and that most of the knowledge that exists on a university campus is not protected by national security laws. Nevertheless, every institution should be able to demonstrate that they have taken the necessary measures to comply with laws protecting sensitive technology.

But the most effective arguments focus on the nonfinancial benefits of international students. They strengthen the learning environment for all students, providing different experiences and perspectives in and out of the classroom. And by admitting only the best students, regardless of nationality, the institution improves the learning environment for everyone.

Internationalized institutions are good for their communities. Most communities in the United States have been touched by globalization through trade, investment, and migration. Broadly speaking, larger urban areas have benefited; smaller cities and most rural areas have lost. A recent project studied the impact of U.S. foreign policies on the state of Ohio, demonstrating that many parts of the state have benefited from export growth and inward foreign direct investment, while other parts have been devastated by import competition and the relocation of jobs to Mexico and other countries. The study demonstrated that foreign investors are attracted to areas where state and local government, the private sector, and higher education are already working together on community and economic development. In addition to the traditional role of workforce training and development, internationalized institutions can share their expertise on foreign countries, provide foreign language training, engage in research partnerships with the private sector, and contribute to a more welcoming environment for foreign nationals. On the latter, the presence of international students and faculty can be an important factor, and a different study has shown that foreign investors are attracted to communities that have an existing international population.

Internationalized institutions are good for the country. For the past half-century—through Democratic and Republican presidencies alike—the United States has pursued the goal of promoting stable democracies around the world, the ideal being democracies that have economic systems that are based on a strong, dynamic private sector. In addition to “hard” policies like trade agreements and treaties, “soft” policies promote these goals through development aid and educational and cultural exchange. While these official programs are important, they are tiny in comparison to a wide range of private activities that promote American values, from movies and television to higher education. International students at American colleges and universities return to their countries with a deeper, nuanced understanding of American society and values. Every board member and campus leader should have compelling stories of international graduates who have returned to their home countries to positions of power and influence.

After being in crisis mode for so long, it may be challenging to think about where you want your institution to be in five to ten years. Internationalization should be an important part of that vision, and international students will be critical to your success. They will strengthen your finances, sharpen your value proposition, and make your campus a more attractive place for all students. As a board member, you are in the ideal position to promote and implement this vision. An ambitious but realistic international plan, developed with broad stakeholder input, will serve as your roadmap.

Brad Farnsworth is principal at Fox Hollow Advisory, a consulting firm that focuses on international higher education strategy. He has worked at Yale University, the University of Michigan, and the American Council on Education, where he served as the vice president for global engagement. He will be leading a session on international strategy at the AGB National Conference on Trusteeship in April 2023 in San Diego.

Resources

https://services.intead.com/blog/topic/recruitment-budget/page/3

https://services.intead.com/blog/spotlight-on-student-first-approach

https://opendoorsdata.org/data/international-students/

https://www.aieaworld.org/aiea-books#Handbook2ndedition

https://www.acenet.edu/Research-Insights/Pages/Internationalization/Mapping-Internationalization-on-U-S-Campuses.aspx