It should come as no surprise to trustees that boards have come under increased pressure in recent years to be more purposeful in the how they govern, specifically when it comes to mission and overall governance. There are several possible reasons for this increased attention on mission and government but a pioneer in the field of governance and investment research, Keith Ambachtsheer, identifies three most likely explanations. In his foreword in The Trustee Governance Guide: Five Imperatives of 21st Century Investing, he reflected on the three main reasons nonprofit organizations have become increasingly focused on their mission and governance in recent years.¹

■ Governance as a process is finally receiving the bright spot it deserves;

■ The time has come to recognize the rise of behavioral economics and its lessons for trustee decision making; and

■ Sustainable investing is increasingly displacing “quarterly capitalism” as the philosophical foundation for long-term wealth creation.

What boards of trustees need to ask themselves is this crucial question: “How much does board governance matter to investment returns?” It is this question and the research that I have conducted for nearly a decade with Sarah Peck, associate professor of finance, at Marquette University, that have provided the impetus for the creation of the “Five Stewardship Imperatives” framework.

Honor and Responsibility

To serve as a trustee for an organization with investment authority is a rare and special calling. Here in the United States it might surprise people to learn that nearly 80 percent of financial assets falls under the purview of an institutional board (e.g., endowment, foundation, pension plan, etc.). It may surprise them even further to learn that only about 1.5 percent of the working population serve in such a capacity.²

So, for the select few, it is no doubt an honor to serve. Then, why is it such a responsibility? When considered across the main three categories of social goods, namely, retirement security, education and a catch-all category, philanthropy, which covers welfare, culture and the arts (plus the environment), the answer is clear—trustees play a fundamentally important role in our economy and society.

Retirement Security

With so many Americans largely unprepared for retirement, and despite the diminished role of the defined benefit plan, there are still millions of Americans, especially public employees, who depend on the benefit payments of pensions. For 50 million Americans, this will cover anywhere from a quarter to half of annual household spending during and throughout retirement.³

Education

For the nearly 5,500 higher educational institutions in the United States, the endowment fund is a source of competitive advantage, as well as the key to a sustained mission, especially in an age when budgets are tighter and enrollments are declining. For many students that will see some portion of college debt in their future (the average student graduates with $37,000 in debt), the endowment is a vitally important source of scholarship funding and support.

Philanthropy

Public foundations annually contribute nearly 20 percent of all charitable giving or approximately $60 billion. In addition to being a source of financial support to cultural, poor, and marginalized groups, they can also play a role in advancing social change.

Performance

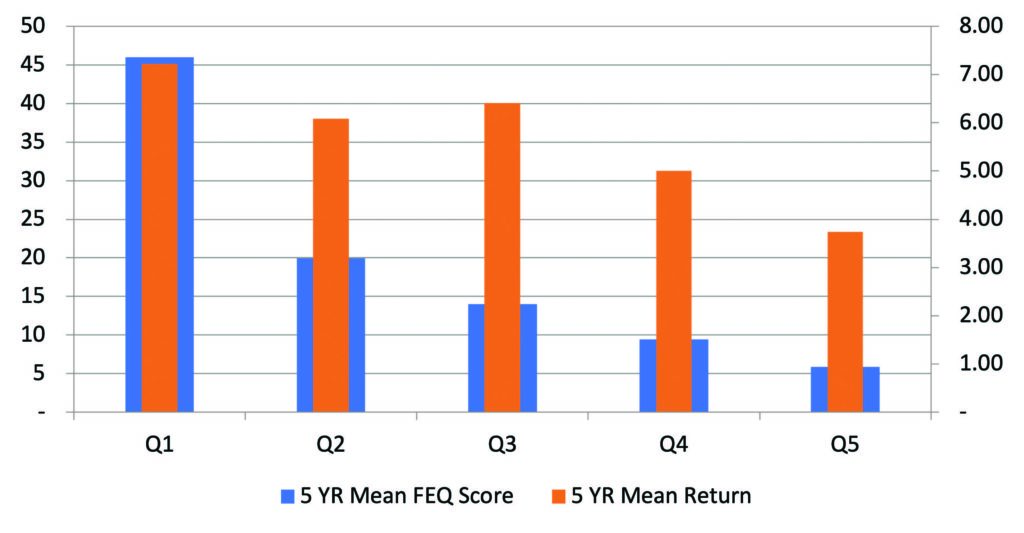

So, how well do trustees do at this job? We answered that question in our study of investment boards, and the answer was mixed. As shown in Figure 1, some did exceptionally well, but most (60 percent) performed at or below the average, and the average was lackluster. The question is how much could we tie back to governance? As it turns out we could explain between 78 percent and 94 percent of the variation in returns based on our governance framework, and this was predictive over a 12-month period.

Figure 1: Boards and their Annual Investment Returns (5-year Average)

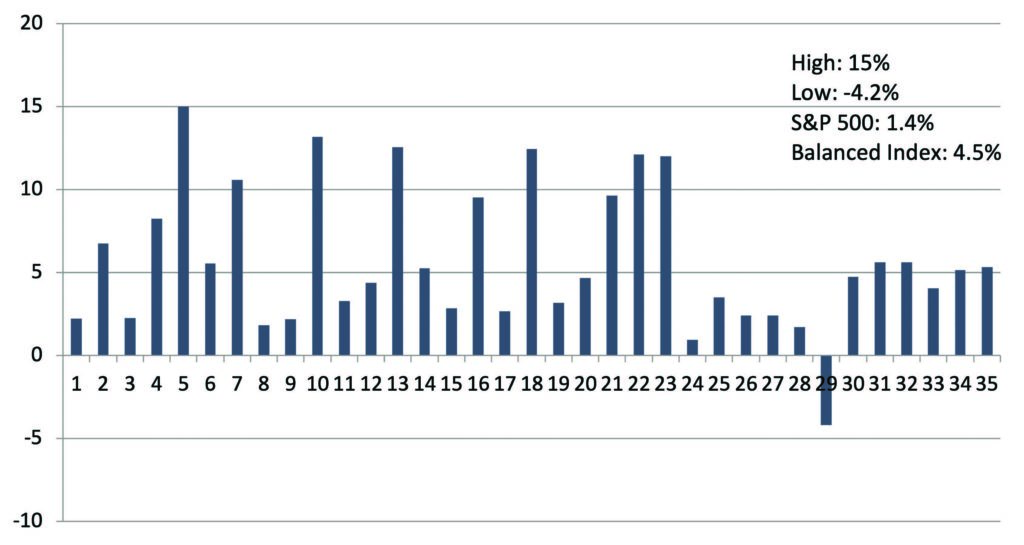

Consistent with these findings, when we further analyzed the organizations’ governance structure, we found that those in the top quintile of governance performance—as measured by the Fiduciary Effectiveness Quotient (FEQ) our summarized measure of governance—outperformed the bottom quintile by a significant margin (see Figure 2). The annual returns were nearly double. In fact, what was most encouraging is we found just marginal governance improvements could have a positive impact, e.g., a one-unit improvement in the FEQ saw, on average, an increase of 0.36 percent in annual return.

Figure 2: Quintile Governance Performance (FEQ) Compared to Investment Returns (percent)

The First Imperative: Be Well-Governed

So, our first imperative is obvious: be well-governed. For that we break fiduciary effectiveness down into three main parts: structure, process, and people. This, by the way, applies to every asset ownership organization regardless of their respective management model; the governance issues are the same. So, it does not matter whether an organization is working with an external consultant, running as an outsourced chief investment officer (OCIO), or managing things in-house and directly.

The key elements of structure are board professionalism…is this an experienced board? Board composition…who is on the board: insiders or outsiders? Elected or appointed? The level of board engagement…do they attend meetings, and how much board representation are on the investment and audit committees? And how transparent…how much does the organization disclose and report to its stakeholders and beneficiaries? It also includes the role of staff and the consultant, we found both are very integral to the success of the organization. Institutional knowledge…how much continuity is present in the organization (i.e., is there much board and staff turnover)? And finally, diligence…to what extent does the board fulfill its main function of running a streamlined and effective fiduciary process?

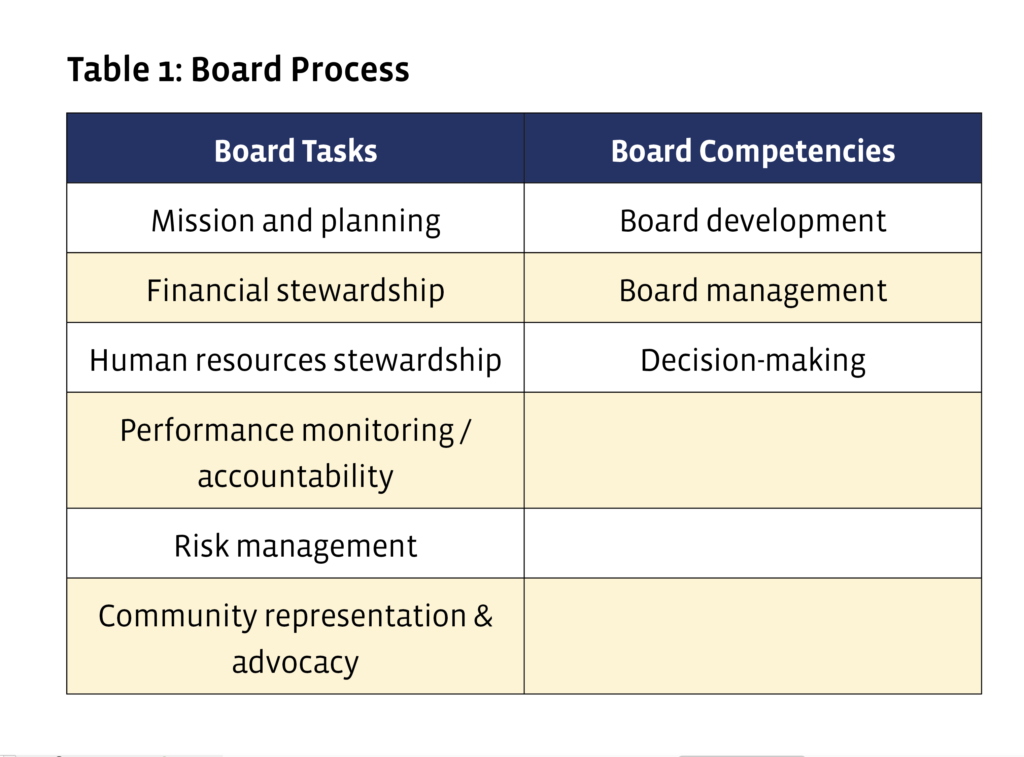

Board process takes place within the just noted structure and is composed of two main areas: Board Tasks and Board Competencies. See Table 1 for a breakdown of each.

Last, but not least, is the people part of the equation: The bottom line is it takes good people to run great organizations. This includes a board with strong leadership; a culture that is both open and fosters trust; board members who are competent and experienced; a board that is diverse with differing points of view; and finally, a board that has constructive group interactions/dynamics.

The Second Imperative: Be Knowledgeable

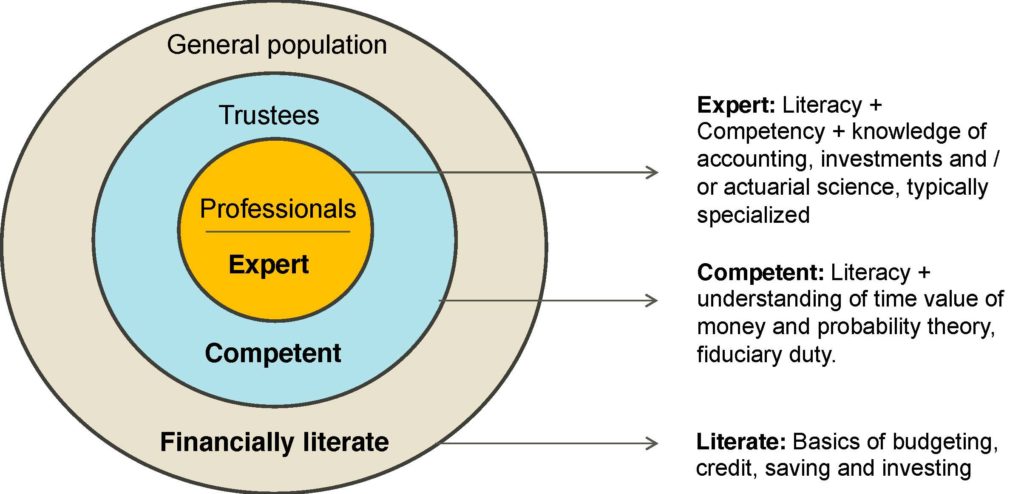

How much knowledge do board members need? Figure 3 illustrates the three levels of financial literacy.

Figure 3: Financial literacy: How much do you need?

For trustees, they need, of course, the same financial literacy of the general population—budgeting, savings, investing, and credit—plus the ability to understand the time value of money for investment decisions, a basic working knowledge of probability theory as it relates to risk management and the fiduciary duties of a trustee. Not everyone needs to possess the specialized knowledge of investment professionals, but they should be aware of two forms of potential human shortcomings in investing—operational errors and behavioral biases—and how to safeguard against them.

Behavioral finance has changed the way we fundamentally view the investor, and board trustees of investment organizations are not immune. This field of research has effectively challenged the rational expectations model of neoclassical economics. The theory asserts that people are not walking calculators, seeking optimality at every given point, but rather they are emotional decision-makers that are often lazy, rushed, or pressured, and therefore, seemed doomed to repeat the same errors over and over.

Combatting these biases, particularly in the governance setting, requires education and training. It also requires strong and engaged leadership to help foster an open and thoughtful arena for deliberation, debate, and open communication. This can be a tall order for many boards that may only meet four times a year for a couple of hours at each meeting.

The Third Imperative: Be Diversified

Diversification, as a principle of risk reduction, is an old concept. For today’s modern board it is a must. However, the challenge in today’s world is not whether to diversify but rather where to stop with it. Options for portfolio selection are almost limitless, and certainly not all options are of equal value or merit.

To start with there are approximately 100,000 publicly traded stocks globally, and a similar number of corporate bonds. In the sovereign and municipal fixed income universe, there are over one million unique issues trading in the market. And, of course, the mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and hedge funds that slice and dice, and re-slice and re-dice this group of stocks and bonds are in excess of 30,000 products. And just like restaurants in New York City, there are dozens opening and closing every day.

To remain fiscally sound, most nonprofit boards must keep sight of three levers: spending, fundraising, and investments. For investments, return targeting is nothing more than goal-setting, and then lining up the allocation and investments to support it. What trustees should be focused on is optimal, well-timed, not overly complicated and based on the simple proposition that the institution needs to generate sufficient cash flow and earnings to fund current and future obligations.

One question we worked to address in The Trustee Governance Guide is how large the endowment needs to be. There is actually a formula! Boards that are most effective are those that take the time to understand what resources are needed to support the organization now and in the future, and also keep an eye on intergenerational equity, i.e., how much is spent now for the current generation (of students, retirees, etc.) versus the future. From that analysis, they are able to work into the right diversified allocation of investments that will serve the organization short and long-term and over changing market cycles.

The Fourth Imperative: Be Disciplined

We can segment discipline into two buckets: governance functions and investment functions. The list of governance functions is longer and should come first.

Boards need to do the following:

■ Set goals and be engaged

■ Document, review, and update policy as needed

■ Bring on new ideas, by periodically rotating the board

■ Orient new members

■ Undertake board self-assessment

■ Conduct the RFP process, and for the same reason that the periodic turning of the board is good, occasionally change the consultant

■ Keep an eye on more than just the investments; they also need to monitor the finance and operations of the organization

And yes, the board is responsible for certain investment functions. While a fair amount can be outsourced, what cannot be outsourced is the ultimate fiduciary obligation of oversight. Boards need to control costs, but not let cost control overwhelm other considerations. In our research, we found that “cost-cutting” boards tended to sacrifice performance over time.

Board self-assessment is incredibly important to helping ensure the success and effectiveness of boards. And while virtually all public companies and many nonprofits undertake board self-assessment every year, this is a task that many still need to incorporate in their annual reviews. The benefits of self-assessment are many: in addition to streamlining communication they can help clarify (or rediscover) the mission and objectives of the organization; and help identify board strengths, areas in need of improvement, knowledge gaps, priority items and areas of commonality, and disagreement.

There are a number of self-assessment tools in the market, but one of the best comes from a Canadian governance expert, Mel Gill, who wrote the book Governing for Results.

The Fifth Imperative: Be Impactful

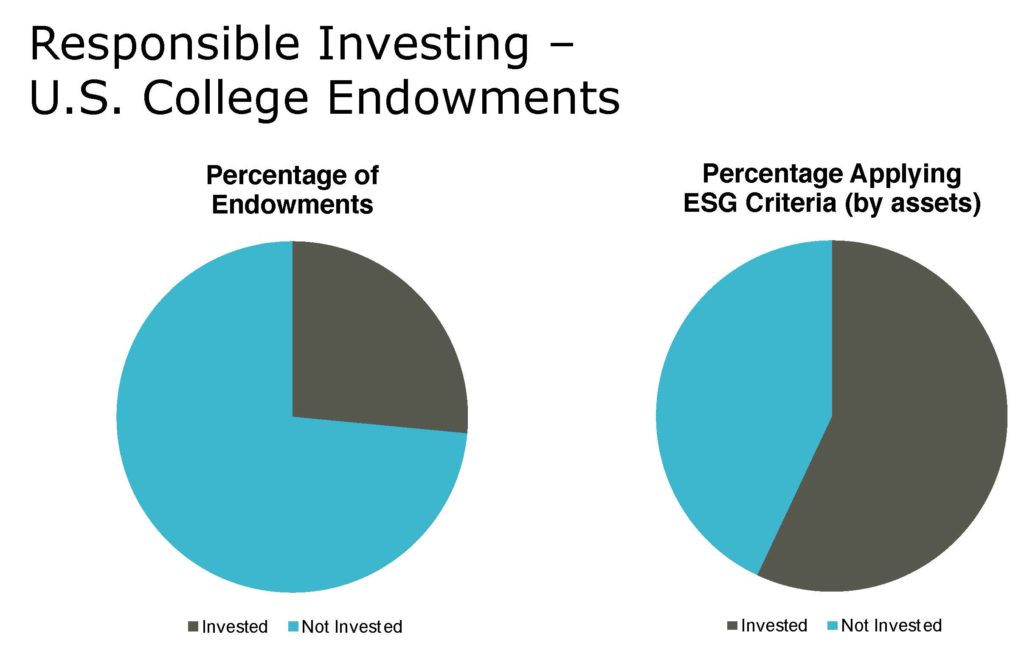

When Yale Endowment’s Chief Investment Officer David Swensen, wrote his “Letter on Climate Change” in 2014, his action helped precipitate a “Stampede into ESG.” Nowhere has ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance factor-based investing) gained greater traction than with college endowments. By 2018, nearly 60 percent of investments (by assets) in college endowments are in ESG-oriented investments (see Figure 4).4

This includes “integrated” investments where investment managers factor ESG risks into their investment process, or “thematic” investments, which “screen in” certain types of investments based on their ESG profile. At the same time, companies and issuers have scrambled to increase their annual disclosure around sustainability, and today nearly 90 percent of S&P 500 companies (and a growing number beyond the 500) file annual CSRs or Corporate Sustainability Reports.

Figure 4. Responsible Investing by U.S. College Endowments

This move into ESG, impact, or responsible investing, has left a number of boards scrambling to catch up. It has created a number of questions for boards, such as what is it to begin with—there is a fair amount of confusion around terminology, how do we go about it and does this pose a fiduciary conflict? Understanding the difference between ethical investing and ESG investing, is something a number of both faith-based, and non-faith-based organizations, are struggling with right now. In fact, during the ESG session at the Commonfund Stewardship Academy, where I was on faculty last summer, Deborah Spalding from Commonfund, asked the group of around 60 participants, how many organizations had implemented a responsible investing program, and only three people raised their hands. But when she followed up with the question, how many are currently looking at implementing such a program, just about every hand was up in the room.

This move into ESG, impact, or responsible investing, has left a number of boards scrambling to catch up. It has created a number of questions for boards, such as what is it to begin with—there is a fair amount of confusion around terminology, how do we go about it and does this pose a fiduciary conflict? Understanding the difference between ethical investing and ESG investing, is something a number of both faith-based, and non-faith-based organizations, are struggling with right now. In fact, during the ESG session at the Commonfund Stewardship Academy, where I was on faculty last summer, Deborah Spalding from Commonfund, asked the group of around 60 participants, how many organizations had implemented a responsible investing program, and only three people raised their hands. But when she followed up with the question, how many are currently looking at implementing such a program, just about every hand was up in the room.

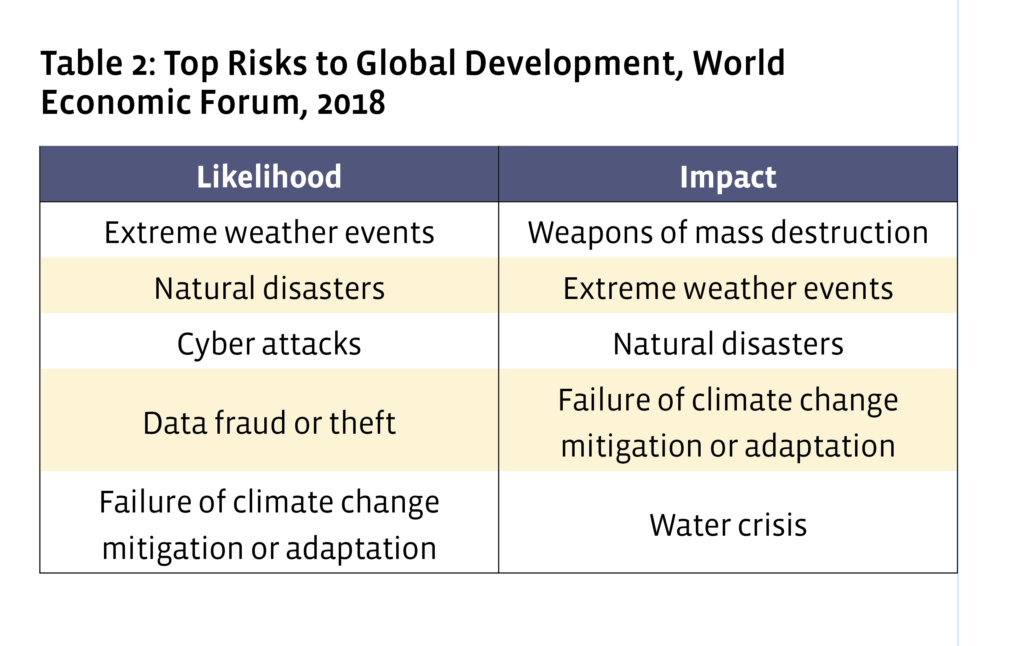

Quickening the pace of ESG investing is the awareness of increased risk in the world due to climate change. Barron’s highlighted that in an article last year.5

One is to see how the physical facilities of the S&P 500’s constituent companies are affected by hurricanes, sea-level rise, and heat stress. How is this important to investors? Thanks to globalization, “you’re exposed” no matter where a company has its headquarters…

And the World Economic Forum puts together its annual list of top risks to Global development shown in the table below. Note climate change related risks dominate in each column. This was again a major topic of discussion at Davos in January of this year.

But these risks aren’t limited to environmental changes. ESG risk can come from any number of issues (governance and social factor risk), and each has its own story. Boards integrating a framework, whether it be for the purpose of ethical considerations, or with the intention of driving better performance results, may be faced with similar concerns. See Table 3 for a sample list of companies and organizations where ESG factors clearly contributed to the negative outcome for each, whether it was for a period of significant downturn in security performance or led to ultimate insolvency.

Figure 5: Organizations Impacted by ESG Factors and Overarching Headline Issue

Organization Headline Issue

Boeing Safety (737 Max)

BP Environmental disaster (Deepwater Horizon)

City of Detroit Municipal bankruptcy

Enron Fraud and corporate bankruptcy

Equifax Major data breach

Facebook Privacy issues (Cambridge Analytica)

Puerto Rico Municipal bankruptcy

Lehman Brothers Fraud and corporate bankruptcy

Volkswagen Fraud (carbon dioxide emissions)

WorldCom Fraud and corporate bankruptcy

These issues need not overwhelm boards. Developing clear policies around these topics with defined processes is the key. A number of tools have come into the market in recent years to aid investors both in the process of investment selection and in the reporting of results. Organizations that can successfully navigate their way of being impactful will find that not only do they stand to generate better results, but that many of their stakeholders will be gratified at the way they are going about it.

Final Thoughts

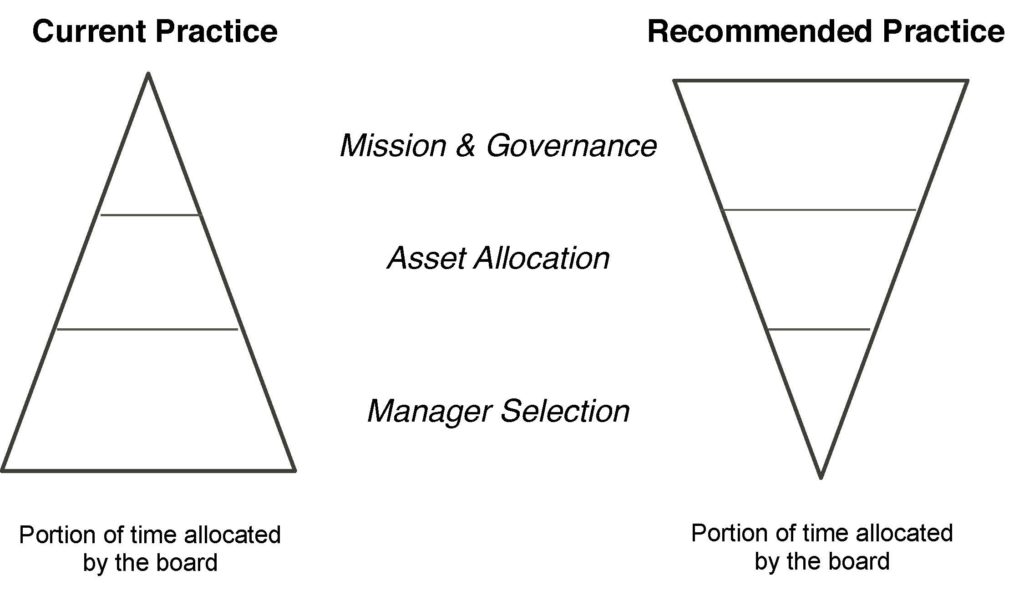

I challenge nonprofit investors to “invert the pyramid” (see Figure 5). By that I mean how to allocate precious board time across three key topics: mission and governance, asset allocation, and manager selection. Boards and investment committees in general spend too little time on mission and governance, not enough time on understanding how the allocation will support organizational needs now and in the future, and too much time on manager review and selection.

Figure 6: Invert the Pyramid

Boards should also know about the trend among organizations to transition to the OCIO model mentioned earlier in the article. Keeping tabs on the myriad investment managers that reside within a given portfolio is a big job, and it is not too much for a board to ask for help in this context.

Directing attention to a number of key governance functions we laid out earlier and describe in detail in The Trustee Governance Guide, such as taking time for board self-assessment, are among a number of things boards can do to drive their fiduciary effectiveness. Improved results will bear out over time. With that I will close with one of my favorite quotes from Gordon L. Clark and Roger Urwin on governance:

Good governance by institutional fund asset owners makes a significant incremental difference to value creation as measured by their long-term risk-adjusted rate of return…[F]unds can create more value if they correctly assess their governance and determine an investment strategy commensurate with their capabilities.

Christopher K. Merker, PhD, CFA, is a director with Private Asset Management at Robert W. Baird & Co. He holds a PhD in investment governance and fiduciary effectiveness from Marquette University, where he teaches the course “Sustainable Finance.” Executive director of Fund Governance Analytics (FGA), an ESG research partnership with Marquette University, he is a member of the CFA Institute’s ESG Working Group and publishes the blog, Sustainable Finance, which covers current topics around governance and sustainability in investing. He is co-author of the book The Trustee Governance Guide: The Five Imperatives of 21st Century Investing.

References

- Merker, Christopher K. and Peck, Sarah W., The Trustee Governance Guide: The Five Imperatives of 21st Century Investing, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, pp. viii-viii

- Ibid, p. x

- U.S. Census, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2012), and Pension Rights Center (2015)

- CommonFund Study of Responsible Investing,” April 2015 (52 of 200 respondents). Includes SRI, ESG, Impact, Divestment of Fossil Fuels US SIF “Snapshot: Educational Endowments and Sustainable Investing,” January 8, 2018 ($293 billion of $515 billion in total assets; 805 respondents to NACUBO Survey)

- https://www.barrons.com/articles/companies- climate-change-risks-51548451729

TAKEAWAYS

■ The three main reasons that nonprofit organizations have become increasingly focused on their mission and governance recently is that the process of governance is receiving a bright spot, it is time to recognize the rise of behavioral economics and its lessons for trustee decision making, and sustainable investing is becoming the philosophical foundation for long-term wealth creation.

■ Trustees play a fundamentally important role in our economy and society. Eighty percent of financial assets in the United States fall under an institutional board. They impact retirement security, education, and philanthropy.

■ Good governance comes down to structure, process, and people. Structure refers to who is on the board, how the board is organized and created, and the roles the board plays in the organization. Process is broken down into board tasks and board competencies. People refers to board culture, leadership, and the group dynamics within the board itself.

■ There are some imperatives that all governing boards should keep in mind. The first two are being well-governed and being financially literate. The third is to be diversified. This means keeping sight of the three levers: spending, fundraising, and investments. The fourth is to be disciplined. This means setting goals and keeping on top of the governance functions of the board. The last imperative is to be impactful, to make a difference in society.

Share on LinkedIn